Infrastructure Progress Review 2022

Published:

Our annual assessment of the government's progress on implementing its commitments on infrastructure.

Foreword

In last year’s review we applauded government for publishing the UK’s first National Infrastructure Strategy, informed by the Commission’s own recommendations - and particularly for doing so in the midst of the Covid-19 pandemic.

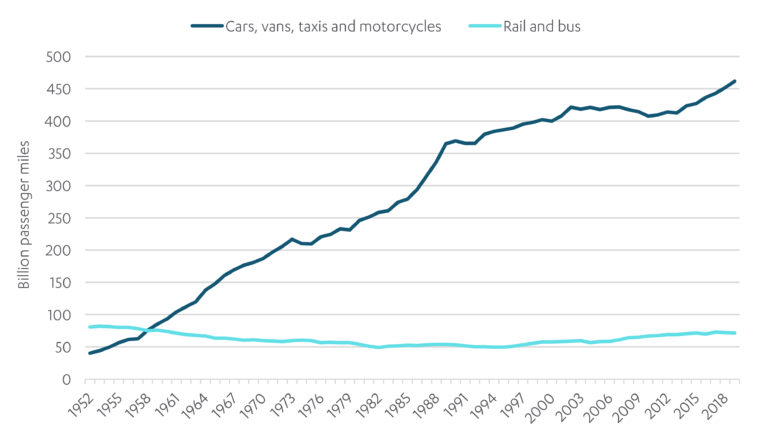

This year, it is right to further recognise the increased investment the government has indicated it will make in national infrastructure. As well as a £100 billion commitment over the next three years, it has also lifted the ‘fiscal remit’ – the funding envelope within which the Commission must cost our recommendations – to 1.1 to 1.3 per cent of GDP from 2025.

This potentially represents billions of extra pounds in spending on preparing our transport, energy, flood resilience, water, waste and digital networks for the future.

Through the Strategy and related announcements, government has set clear, long term goals for most infrastructure sectors. And there has been some progress, with the establishment of the UK Infrastructure Bank this year and the continuing expansion of gigabit capable broadband and renewable energy generation.

But it is also our role, as independent advisers, to sound a warning when we think progress is insufficient towards the goals to which government has committed, and around which there is almost universal consensus: the need to reduce greenhouse gas emissions, become more resilient to climate change and ensure economic opportunity is spread more evenly across the country.

Reviewing the current state of key areas of policy and delivery, gaps are opening up between aspiration and execution.

We highlight several areas of concern, where urgent action is needed to avoid serious risks to delivering the objectives of the National Infrastructure Strategy.

These include the need for a comprehensive energy efficiency push to hit the government’s own target for all homes to be rated EPC C or above by 2035.

We also need to devolve five year funding settlements for transport spending to local authorities beyond the current metro mayoralties.

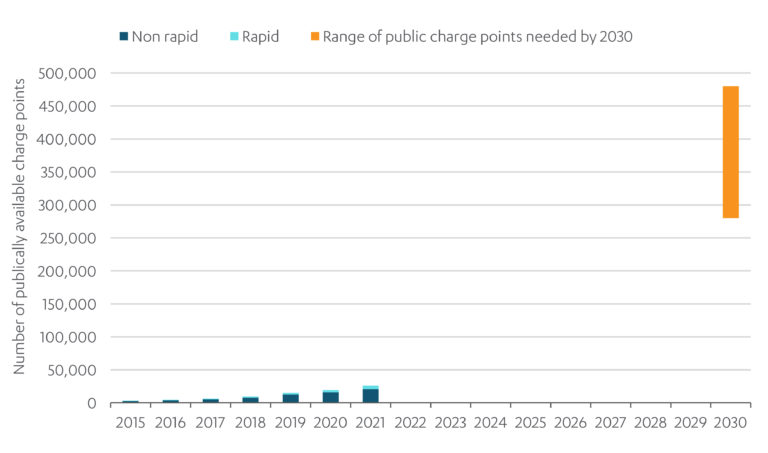

And we need to turbo charge the roll out of electric vehicle charging points, accelerating the installation of both rapid and on-street charging facilities so that the 2030 date for the end of the sale of new petrol and diesel cars remains viable.

At a time of significant global volatility alongside concerns about rising living costs, we appreciate that sticking to a long term strategy is not easy.

But it is the only way to address the stubbornly difficult problems that will not become any easier or cheaper to solve by delaying action – and the quicker we tackle them, the quicker society and our environment will reap the benefits.

Sir John Armitt, Chair

Next Section: Executive summary

Clear, long term goals

Executive summary

Clear, long term goals

At Spending Review 2021, government made a firm funding commitment to support economic infrastructure over the next three years. At the same time, it signalled a longer term commitment to investing in economic infrastructure by increasing the Commission’s fiscal remit to 1.1 – 1.3 per cent of GDP each year from 2025 to 2055.

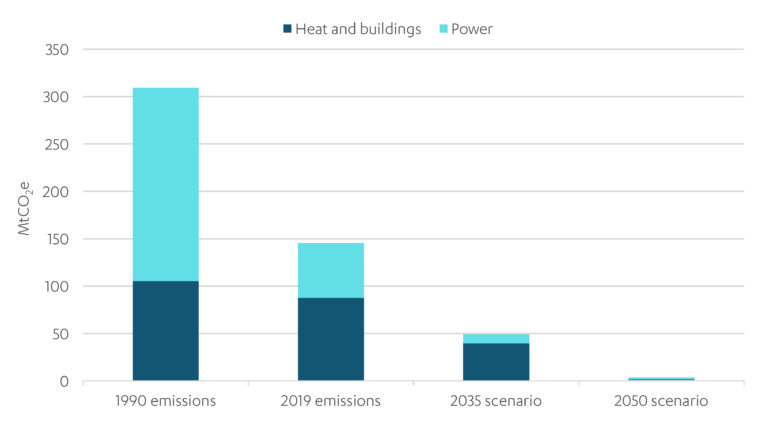

These were positive commitments. Delivering the economic infrastructure the country needs is critical to achieving sustainable economic growth, boosting competitiveness, improving quality of life, supporting climate resilience and transitioning to net zero carbon emissions by 2050. Economic infrastructure will also need to adapt to behaviour changes that may result from the shock caused by the Covid-19 pandemic, such as new working and commuting patterns.

But to ensure this money is spent effectively, government needs its infrastructure strategy to be sound and its policies robust. And in the context of a tight fiscal environment and rising costs of living, each pound spent must return maximum value.

In 2020, government responded to the Commission’s first National Infrastructure Assessment by publishing a detailed and comprehensive approach to infrastructure policy in the National Infrastructure Strategy. Over the past year it has backed this up with other key strategies, including the Net Zero Strategy, the Levelling Up White Paper, and the Environment Act 2021. The government has now set clear, long-term goals in most areas.

Figure 1: Government has committed to increasing public spending on economic infrastructure

Public expenditure on economic infrastructure

Source: Commission calculations, HM Treasury (2021), Spending Review 2021. Note the profile of the £100 billion spending commitment on economic infrastructure from Spending Review 2021 between 2022-23 and 2024-25 has been assumed flat in percentage of GDP terms.

Some good achievements

Some of the Commission’s key recommendations have been delivered or progressed this year. The UK Infrastructure Bank has been established and is already making deals. Gigabit broadband coverage continues to accelerate rapidly and now reaches over 65 per cent of premises. More renewable electricity capacity was once again deployed and government has committed to hold contracts for difference every year, which will support further deployment. Government also published The Integrated Rail Plan, its response to the Commission’s Rail Needs Assessment, which set out a realistic plan for major long term investments to improve rail for the North and the Midlands.

Government has also delivered a number of important long term strategies this year including:

- The Net Zero Strategy should be welcomed for setting a clear high level direction for decarbonising the economy, in line with legislated targets.

- The Levelling Up White Paper made commitments to streamlining local growth funding and to significantly extending devolution.

- The Environment Act 2021 became law, giving government powers to mandate cooperation on regional water plans and setting out a framework to make progress on increasing recycling rates and separating food waste collection. The Environment Act 2021 also legislates to require Nationally Significant Infrastructure Projects to achieve biodiversity net gain.

But overall, it has been a year of slow progress

Despite these achievements, overall progress against key goals over the past year has been too slow. Little progress has been made on decarbonising heating, increasing the energy efficiency of homes, delivering higher recycling rates, installing electric vehicle charge points across the country, or reducing per capita water consumption.

And some of the strategies government has developed over the last year lack detailed policy plans, leave key gaps, or do not go far enough. For example, the Net Zero Strategy leaves major gaps around the pathway for heating decarbonisation, how uptake of energy efficiency measures can be significantly increased, and, crucially, how the costs of transitioning to low carbon infrastructure will be fairly paid for.

One of the key questions that many of these strategies do not address is who will pay for new infrastructure. Household expenditure, for both capital and operating expenditure, on economic infrastructure has remained broadly stable at around £7,000 per year for the past two decades. But for new infrastructure to be built — whether that be infrastructure for decarbonising freight, large scale technologies to remove greenhouse gases directly from the atmosphere, or improvements to resilience — somebody has to pay. Ultimately, that will either be taxpayers, consumers, or a combination of both. But ensuring the costs are distributed fairly is critical. Delays to decisions on who pays are now holding up delivering infrastructure, including low carbon heat and energy efficiency. Open and honest conversations, followed by clear decisions, are needed to address this.

Falling behind in many infrastructure sectors

Slow progress over the last year means that government is not on track to deliver on many of the policies and targets set out in the National Infrastructure Strategy.

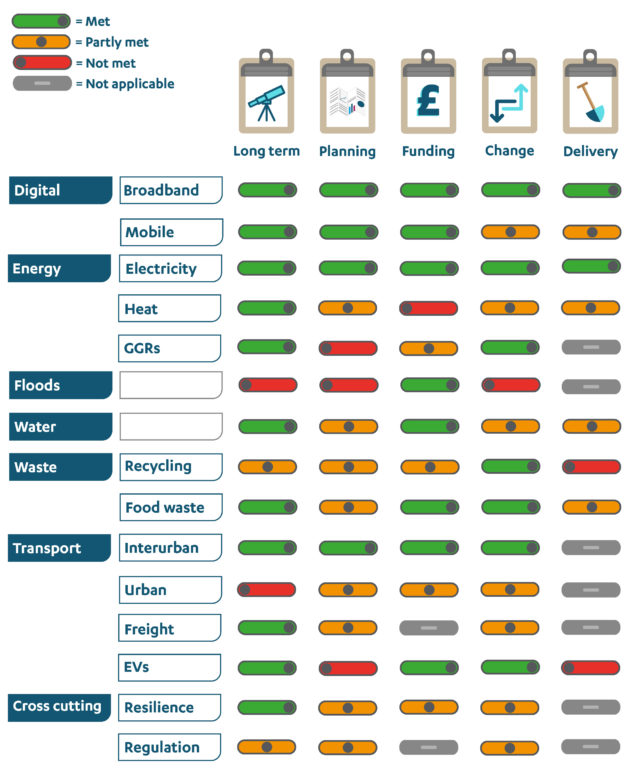

The Commission monitors government’s progress against the recommendations the Commission has made on an annual basis. New infrastructure can rarely be built quickly. But steady progress is needed to deliver long term changes. The Commission has used five tests, described below, to assess government’s actions over the last year:

- Taking a long term perspective – government should look beyond the immediate spending review period and sets out its expectations over the next 10 to 30 years

- Clear goals and plans to achieve them – there should be a specific plan for government policy ambition or endorsed Commission recommendations, with clear deadlines and identified owners

- A firm funding commitment – where necessary policy ambition should be supported by firm funding commitments commensurate with the level of investment needed to deliver the required infrastructure

- A genuine commitment to change – the Commission has recommended that, in some areas, fundamental shifts in policy are required; government policy should respond in the same spirit

- Action on the ground – looking beyond policy, infrastructure should be changing in line with the Commission’s recommendations, providing better services to consumers and taxpayers now.

Summary of progress in each economic infrastructure sector

Digital

Government has made a genuine commitment to change digital connectivity across the country. Delivery of gigabit capable broadband networks is progressing rapidly and, in 2021, gigabit capable coverage was extended to 65 per cent of premises. If operators deliver on their published plans, government will likely achieve its target to deliver 85 per cent gigabit capable coverage by 2025 and nationwide coverage by 2030, with the support of the £5 billion subsidy programme Project Gigabit. On mobile, 4G coverage from at least one operator now extends to around 92 per cent of the UK landmass, and the new Shared Rural Network agreement should increase this to 95 per cent by 2026. But, across both gigabit and 4G networks, government must ensure that areas that are hard to reach do not get left behind.

Positive progress has also been made on 5G, with coverage now reaching around 50 per cent of premises. However, the value 5G can provide, beyond just faster 4G, remains unclear. To unlock the full benefits of 5G, government must set out an assessment of the country’s future wireless connectivity needs.

Good progress is being made on developing a national digital twin, but much more work is still needed. Government must continue its support of the national digital twin programme if the country is to realise the benefits of better real time monitoring and simulation of infrastructure systems.

Energy

In 2021, government published strategies on reaching net zero and decarbonising heat and buildings. The strategies contained ambitious long term targets for the coming decades. However, concrete plans and detailed policies are still lacking in some key areas.

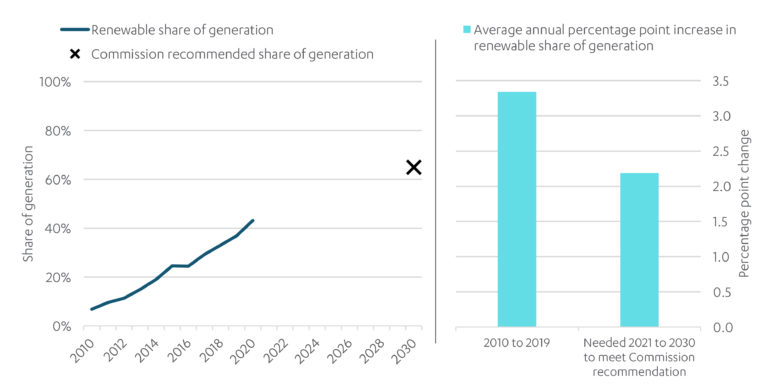

In 2020, renewable electricity generation made up 43 per cent of total electricity supply, an increase of around 6 percentage points on the previous year. Whilst this is expected to decrease in 2021, this is only the result of a low wind year not a change in the underlying infrastructure. Government has sound policy in place to continue this progress over the next decade. However, a significant challenge still remains to meet the government’s ambition of a net zero electricity system by 2035, whilst maintaining security of supply.

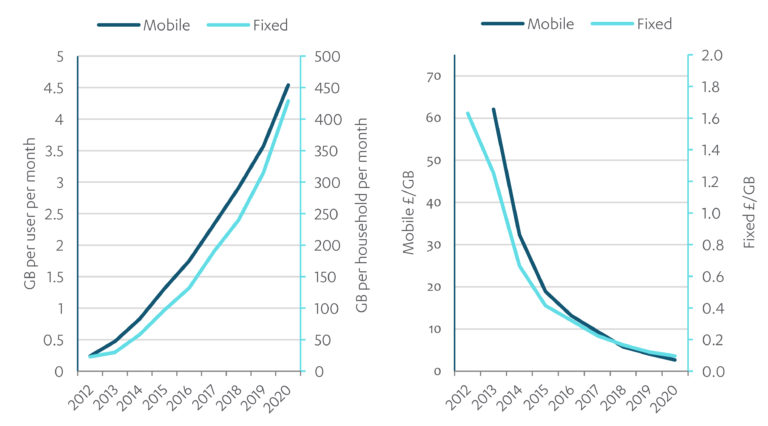

Decarbonising heating is the biggest infrastructure challenge for building a net zero economy and rapid action is needed: emissions from heat need to reduce by around 50 per cent by 2035 and to near zero by 2050 from 2019 levels . In the Heat and Buildings Strategy government set out long term targets for decarbonising heat and improving energy efficiency. But these targets are not currently supported by a delivery plan or clear funding. Annual heat pump installations are around 36,000, far short of the government’s target for 600,000 by 2028 and energy efficiency installations are also falling short of the level needed.

There are unresolved areas government needs to address, including what heating technologies are feasible and where, how to create the right incentives for people to switch from fossil fuel heating, how much investment is required and who will pay for this, and how the transition will be delivered at pace. If government is to meet its targets on heat decarbonisation, it must resolve these questions urgently.

Flood resilience

More than five million homes in England are at risk of flooding, and climate change means the risk is growing. Government has started to act in line with commitments in the National Infrastructure Strategy. Government investment in flood defences has doubled and policies have been revised to emphasise catchment based planning, green infrastructure, and property level resilience. But government has yet to define long term targets for flood resilience. Until it does so, policies and investment are unlikely to fully address the flood risk.

Water

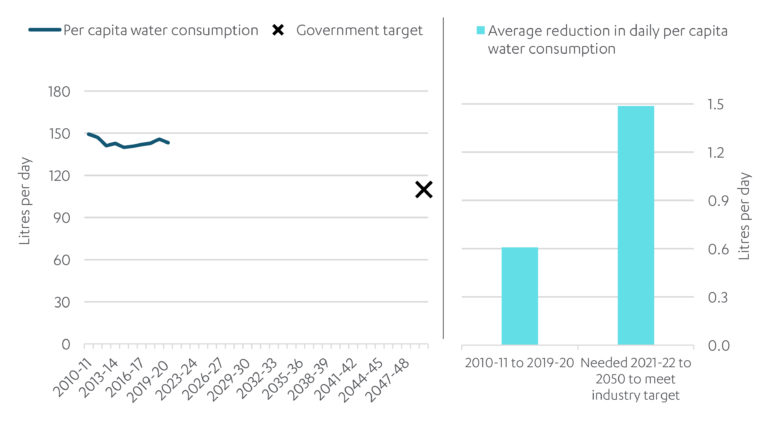

Additional water capacity is needed to avert the real and growing risk of water shortages. In the first National Infrastructure Assessment, the Commission proposed addressing the growing risk of water shortages through a ‘twin track’ approach: reducing demand, while increasing supply. There is some evidence that government, regulators, and industry are making progress reducing leakage and developing new supply infrastructure. But per capita water consumption, already at unsustainable levels, is not yet falling. There are ambitious targets for reducing per person water consumption, but it is not clear whether the government’s new policies will deliver the reductions needed.

The number of serious pollution incidents from water and sewerage remain too frequent. Around 32 per cent of water bodies in England do not have good ecological status due to continuous discharges from sewage, and 7 per cent due to stormwater overflows.

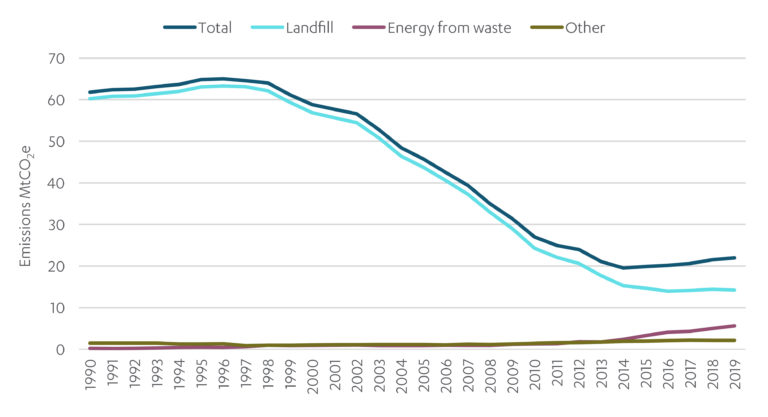

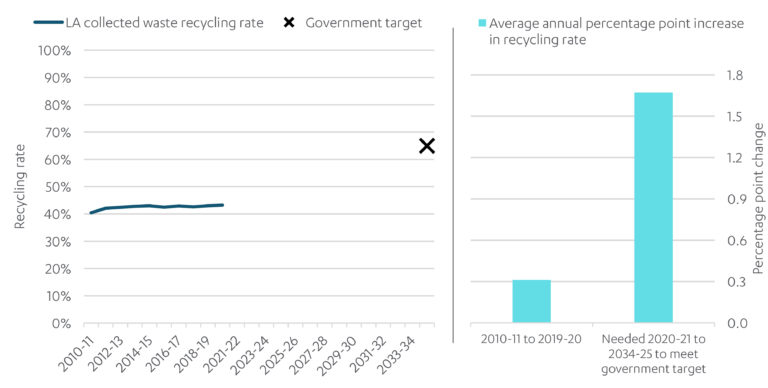

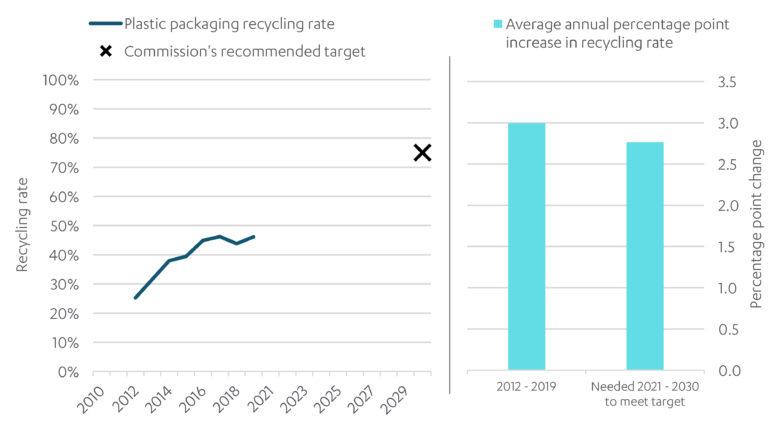

Waste

More action is needed from government to deliver a low cost low carbon waste sector. The Resource & Waste Strategy and the Environment Act 2021 have indicated an ambition to incinerate less and recycle more. However, recycling rates have remained flat since the mid 2010s. Government is off track to deliver its target of 65 per cent municipal waste recycling by 2035.

Transport

The government’s Levelling Up White Paper is ambitious in its scope and aims, although some of its targets lack specificity. It sets out 12 missions to be achieved by 2030, including reducing gaps in productivity and bringing transport networks in major urban centres closer to the standard of London. The Commission welcomes the steps to widen devolution to more local areas and the prospect of expanding the existing devolution arrangements with city regions, starting with the Greater Manchester and West Midlands combined authorities.

But to achieve tangible improvements to local infrastructure in the next eight years, government must prioritise progress in three key areas:

- To achieve the white paper’s objective of having a globally competitive city in each region, government will need to develop a pipeline of mass transit networks for urban centres outside London, beyond the sole commitment that it has made for a new mass transit system for West Yorkshire.

- Fundamental reform is needed to how local transport funding is allocated, with a shift away from competitive bidding between councils for multiple, centrally controlled, short term funding pots, to long term devolved funding settlements. While the white paper promises a plan for streamlining the funding landscape, this needs to be turned into real change quickly. Local areas should have robust monitoring and evaluation plans for the impact of investments, so devolution is accompanied by accountability.

- The planned new devolution deals for local areas in England will need to be in place much sooner than 2030. Local transport authorities in these areas should receive five year integrated settlements covering funding streams for maintenance and upgrades, so they have the planning certainty to develop long term local infrastructure strategies, supported by clear project pipelines. This would mirror the important multiyear transport settlements now in place for the city regions, as recommended by the Commission.

The Integrated Rail Plan provides a long term plan for rail in the north and midlands to build new high speed lines and upgrade and electrify existing lines. It is sensible that the Integrated Rail Plan takes an adaptive approach, setting out a core pipeline of investment that should speed up delivery of benefits. However, progress with the Cambridge-Milton Keynes-Oxford Arc is less positive, with the cancellation of the plans to build the Oxford-Cambridge expressway. East West Rail presents a major growth opportunity for the Arc and government must continue with all phases of the delivery plan. Levelling up should not mean government leaving growth opportunities on the table.

Lack of action on decarbonisation of transport now poses a serious risk to delivering on the Sixth Carbon Budget. The Transport Decarbonisation Plan sets out long term targets for decarbonising the transport sector, including 100 per cent new sales of electric cars and vans by 2030 and a commitment for all new heavy goods vehicles to be zero emission by 2040. But the roll out of electric vehicle charge points is far too slow. Analysis suggests that by 2030 between 280,000 to 480,000 charge points will be needed to facilitate the transition to electric vehicles. By the end of 2021 only around 28,000 charge points had been installed. Progress has been made on decarbonising freight. However, a detailed assessment of the infrastructure requirements for transitioning to zero carbon freight is still needed; this must be included in the upcoming Future of Freight strategy.

If progress is not made on decarbonising transport, this may compromise the country’s ability to have a well functioning transport system, including building new transport infrastructure such as roads which will remain the primary mode of transport.

Cross cutting

The UK Infrastructure Bank was established in 2021, as the Commission recommended, and has already started making deals. Government has also taken positive steps on infrastructure design by endorsing the Commission’s design principles for national infrastructure, which are now incorporated into the Infrastructure and Projects Authority’s assurance regime for major government projects. The government’s recent policy paper on economic regulation showed that it understood the challenges regulation faces and the need for change. The Commission reiterates its recommendation that government should introduce net zero, resilience, or collaboration duties for Ofwat and Ofgem.

Government has accepted the Commission’s recommendations on the need for clear, transparent, and regularly updated resilience standards and for stress testing that ensures standards can be met. And infrastructure resilience also appears to have moved up the public’s agenda, especially following the events of Storm Arwen. The frequency of extreme weather events will only increase with climate change. The test of government’s ambition in this area will be whether the forthcoming National Resilience Strategy provides both the strategic direction and tangible deliverables needed to strengthen resilience.

How to get back on track

Urgent action is needed to ensure the government delivers on its commitments in the National Infrastructure Strategy. Another year of slow progress would make meeting the country’s climate targets unlikely and readying infrastructure for the impacts of a changing climate more challenging. Whilst infrastructure alone is not sufficient to achieve levelling up, it has an important role to play, and significant progress must be made this year to take forward the Levelling Up White Paper commitments.

In this report, the Commission is setting out ten actions government needs to take over the next year to get back on track and deliver on its National Infrastructure Strategy and the Commission’s recommendations. These are not straightforward, but they are necessary.

Priorities for 2022

| Area | Priority action for the year ahead |

|---|---|

| Digital | Set out an assessment of the country’s future wireless connectivity needs and how mobile networks will need to evolve to meet future demand, articulating the balance between what the market can deliver and where government needs to intervene |

| Energy | Improve energy efficiency schemes to put the country on track to deliver the government target for as many homes as possible to be EPC C rated or above by 2035 |

| Energy | Publish a detailed plan to deliver at least the 5 MtCO2 per year of engineered removals by 2030 ambition in the Net Zero Strategy |

| Floods | Set out a long term measurable objective for what flood resilience policy in England is trying to achieve |

| Water | Strengthen and progress plans for reducing per capita water consumption to deliver the targeted 110 litres per person per day by 2050 |

| Waste | Deliver increased recycling rates by finalising policy on key areas such as extended producer responsibility, deposit return schemes, recycling consistency and bans on certain types of plastics |

| Transport | To achieve tangible improvements in local transport, government must: Move away from competitive bidding for multiple, centrally controlled, short term funding pots and make fast progress towards devolving five year integrated funding settlements for transport spending to local authorities outside the city region combined authorities Support local authorities in developing plans for major urban transport schemes in a number of priority cities, including plans to develop a mass transit system for West Yorkshire |

| Transport | Initiate a step change in the rate of deployment of charge points to get on track to deliver the infrastructure needed to facilitate the 2030 end to new diesel and petrol car and van sales |

| Regulation | Building on the publication of the Economic Regulation Paper to complete a review of regulators’ statutory duties |

| Resilience | Set out improvements to resilience standards and stress testing in the National Resilience Strategy |

The Commission’s next Assessment and future challenges

The Commission is preparing the second National Infrastructure Assessment, to be published in the second half of 2023. This next Assessment will make a series of further recommendations to address the key long term challenges facing the country’s infrastructure.

Next Section: Digital

Government continues to make good progress on supporting new digital infrastructure networks. Delivery of full fibre and gigabit capable broadband networks is progressing rapidly. And government has set out ambitious targets for 4G coverage in the Shared Rural Network agreement with industry. But across both fixed and mobile networks, government must ensure that hard to reach areas do not get left behind.

Digital

Government continues to make good progress on supporting new digital infrastructure networks. Delivery of full fibre and gigabit capable broadband networks is progressing rapidly. And government has set out ambitious targets for 4G coverage in the Shared Rural Network agreement with industry. But across both fixed and mobile networks, government must ensure that hard to reach areas do not get left behind.

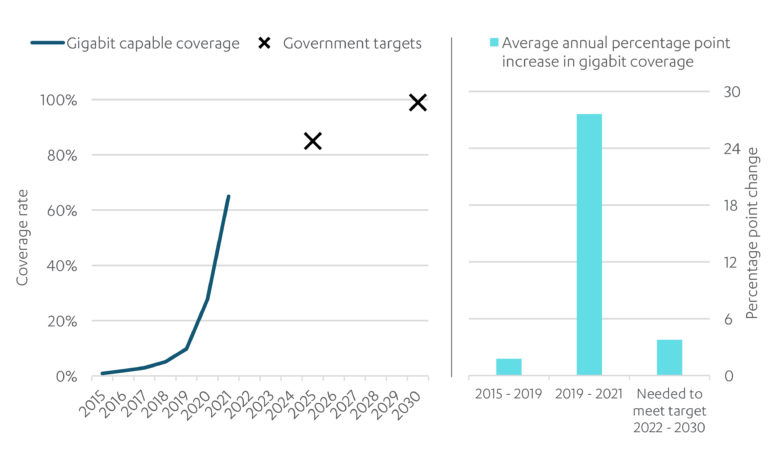

In 2021, gigabit capable coverage was extended to 65 per cent of premises. If operators deliver on their published plans, and progress continues to be made on delivery of government’s £5 billion subsidy programme Project Gigabit, then government will likely achieve its high level targets. This demonstrates a genuine commitment to change.

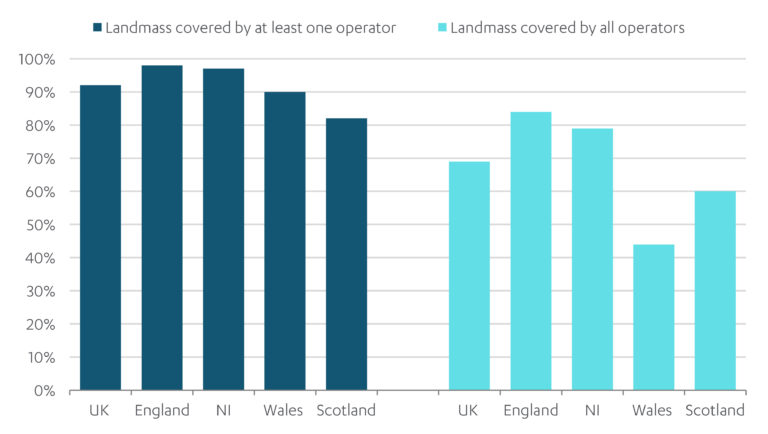

On mobile, around 92 per cent of the UK landmass now has 4G coverage from at least one operator. And the new Shared Rural Network agreement should increase this to 95 per cent by 2026. Positive progress has also been made on 5G, with coverage now reaching nearly 50 per cent of premises. However, the value that 5G can provide, beyond just faster 4G, remains unclear.

Priority action for 2022

Set out an assessment of the country’s future wireless connectivity needs and how mobile networks will need to evolve to meet future demand, articulating the balance between what the market can deliver and where government needs to intervene.

The digital sector

Digital infrastructure covered by the Commission focuses on services accessed by consumers and businesses in two categories: fixed broadband and mobile connections.

- Fixed broadband provides a continuous connection to the internet for homes and businesses, replacing previous ‘dial up’ connections. There are a range of different service levels that fixed broadband can provide, depending on which access technology is used.

- Mobile networks provide voice, text, and data connectivity services to consumers and businesses by using a mobile phones and other connected devices as a terminal.

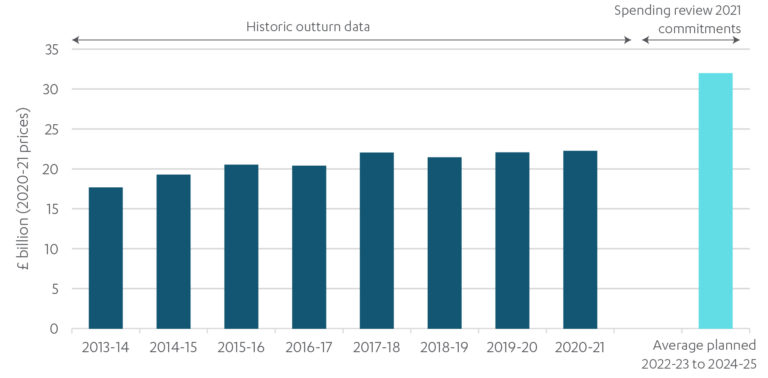

The digital sector continues to perform well. Increases in consumption have been matched by reductions in unit prices (Figure 3). Despite receiving a much higher quality service, consumers pay less for both fixed and mobile services than they did a decade ago.1 The UK’s digital infrastructure has continued to demonstrate good resilience throughout the Covid-19 pandemic. Around 760 outages or disruptions were reported over the last year on both the fixed and mobile networks, the majority of these being caused by hardware failures.2 This is comparable, although slightly higher than, figures for previous years.3 However, there is some evidence that consumers have experienced disruptions to service quality during the pandemic. Survey data found that around 70 per cent of consumers had experienced an issue with their connection over 2020-21.4

The Commission has set out a more detailed overview of the digital sector in Second National Infrastructure Assessment: Baseline Report Annex A: Digital and the Commission’s data on sector performance.

Figure 3: Consumption has grown rapidly over the past decade, but unit prices have fallen at the same time

Data consumption 2012 – 2020 Unit price of data 2012 – 2020

Source: Ofcom (2021), Communications Market Report 2021

Progress against the Commission’s recommendations

Fixed connections

Commission recommendations

In 2018, the Commission recommended that government set out a nationwide full fibre connectivity plan by spring 2019, including proposals for connecting rural and remote communities, to ensure that full fibre connectivity would be available to 15 million homes and businesses by 2025, and to 25 million by 2030, with nationwide coverage by 2033.5 A significant number of premises will be commercially unviable for providers to deliver full fibre, so the Commission also recommended that rollout of full fibre to these premises should be partly subsidised by government.

To accelerate delivery, the Commission recommended that Ofcom should promote network competition through deregulation where possible, and by allowing access to Openreach infrastructure for alternative providers. The Commission also argued that government should improve processes to obtain wayleaves for telecommunications providers, promote the appointment of digital champions by local authorities, and work with Ofcom to allow for copper switch off by 2025.

In its Infrastructure, Towns and Regeneration study the Commission also highlighted that many commercially unviable properties will likely be located in towns. Analysis suggests that around 20 per cent of towns may be reliant on government support to deliver gigabit capable broadband to more than 20 per cent of their premises.6

Government policy

Government has endorsed the Commission’s recommendations on full fibre rollout in the Future Telecoms Infrastructure Review and its Response to the National Infrastructure Assessment.

In the National Infrastructure Strategy, the government set out its goal to deliver a minimum of 85 per cent gigabit capable coverage by 2025.7 In the Levelling Up White Paper government built on this target and set an aim to deliver gigabit capable coverage to at least 99 per cent of premises by 2030.8 Gigabit capable coverage refers to connections that are able to provide download speeds of 1 Gbit/s or higher and can either be delivered through a full fibre connection or a hybrid fibre coaxial cable used by Virgin Media O2. The Commission intends to monitor government progress against its gigabit capable targets going forward.

In March 2021, the government announced Project Gigabit, a £5 billion fund to support the rollout of gigabit capable broadband to homes and premises in the hardest to reach 20 per cent of UK premises, equivalent to around six million premises. The 2020 Spending Review allocated £1.2 billion of this funding for the years between 2021 and 2025. The government has set out the first phases of its procurement programme to extend coverage to hard to reach premises.9

Alongside Project Gigabit, both government and Ofcom have undertaken significant policy reform to ensure that the investment signals are right to support rapid deployment of gigabit capable networks. Ofcom recently published the Wholesale Fixed Telecoms Market Review 2021 – 26, which set out a series of decisions designed to support investment in gigabit capable networks,10 including policies to promote competition between networks, where viable.11 Ofcom has also allowed pricing flexibility for fibre services for the long term while protecting consumers.12 This has been supported by action to remove barriers to deployment, such as Ofcom’s requirements on BT to provide duct and pole access to other operators, and government reforms to wayleaves.

In late 2021, government published its response to an earlier call for evidence regarding access to infrastructure regulations. Government identified areas for improvement but has not yet clarified when it intends to make changes.

Change in infrastructure over the past year

Progress on gigabit broadband coverage has continued over the past year. Gigabit capable coverage has increased from 37 to 65 per cent (Figure 4). The increase in coverage has largely been driven by Virgin Media O2 completing the upgrade of all its network to be gigabit capable.

Industry has also made a series of positive commitments over the past year. Openreach has committed to spend £15 billion to deliver full fibre to 25 million premises across the UK, including aiming to reach three million hard to reach homes and businesses across the country.13 In 2021 Virgin Media O2 announced that it would upgrade its entire fixed network to full fibre by 2028, covering over 20 million premises after accounting for its ambition to grow its network further by 7 to 10 million premises.14 CityFibre have also recently raised around £1.1 billion to fund the rollout of fibre to over 8 million premises.15

Figure 4: Government is on track to deliver its gigabit capable target

Historic coverage and government targets 2015 – 2030 (Left chart) Rates of change in coverage 2015 – 2030 (Right chart)

Source: thinkbroadband (2021), UK Superfast and Fibre Coverage. Note: ‘nationwide’ gigabit coverage by 2030 is defined as at least 99 per cent of premises in Levelling Up White Paper.

Assessment of progress

If operators deliver against their published plans, government will deliver on its high level targets. But some challenges do remain for government in ensuring coverage is universal. Government is taking a long term approach, with funding and market frameworks in place to deliver clear plans, but it is essential that it accounts for how coverage will be extended to hard to reach premises going forward.

- Taking a long term perspective: Yes. Government’s goals for 85 per cent gigabit capable coverage by 2025 and 99 percent coverage by 2030 look beyond the current funding cycle and account for futureproofing the network.

- Clear goals and concrete plans to achieve them: Yes. Government is taking the right procurement approach, focused on premises that lack superfast broadband. Clear plans are in place to ensure that contracts for delivering infrastructure to hard to reach properties are launched as soon as possible.

- Firm funding commitment: Yes. The £5 billion funding for Project Gigabit aligns with the Commission’s own estimates. But it is important that government allocates the remaining funding through future spending reviews, as needed. Market structures and regulation continue to incentivise significant private sector investment in the networks: last year capital expenditure in fixed access networks increased from £3 billion to £3.2 billion.16

- Genuine commitment to change: Yes. While government is making good progress, it must ensure that hard to reach premises are not left behind. Alongside spending money from Project Gigabit to support deployment in areas where the commercial case is weak, it must continue to develop approaches to overcome barriers to access that infrastructure providers face, for example through the recent reforms to wayleave rules.

- Action on the ground: Yes. Good progress continues to be made in rolling out of gigabit capable networks. Government appears on track to deliver its target of 85 per cent coverage by 2025, provided operators fulfil their published plans which are expected to achieve at least 80 per cent gigabit coverage by 2025. Project Gigabit should then be able to support connections to the remaining 5 per cent. However, progress will slow down once coverage has reached all commercially viable premises and only hard to reach premises remain. And as Virgin Media O2 have upgraded their entire network to be gigabit capable, which resulted in a rapid increase in coverage between 2019 and 2021 (Figure 4), coverage can now only be expanded through delivering full fibre connections. This will take longer than simply upgrading existing hybrid fibre connections as Virgin Media O2 have been doing. Achieving nationwide gigabit coverage is a huge civil engineering project. It is therefore essential that the UK maintains a pro-investment policy and regulatory environment.

Mobile Connections

Commission recommendations

In Connected Future, the Commission recommended the expansion of 4G coverage to all UK roads and rail and that government must support rollout of 5G across the country.

To support this, in its study Infrastructure, Towns and Regeneration, the Commission recommended that:

- Ofcom should consider crowd sourced data based on real world usage to improve understanding of mobile coverage and produce insights that can help with further optimising mobile coverage

- Government should partner with towns to run innovation pilots for new communications technologies, including 5G use cases.

Government policy

In 2020, government secured the Shared Rural Network agreement with mobile network operators to increase 4G coverage across the country and reduce both total and partial not spots.17 To do this, the agreement includes a target that, by 2026:

- 95 per cent of the UK landmass will have 4G coverage from at least one operator

- 90 per cent of the UK landmass will have 4G coverage from all operators

- Collectively operators will provide additional coverage to 16,000 kilometres of road.18

The deal includes over £500 million of public investment, which is matched by over £500 million of private sector investment.19

Government is still developing its strategic approach to 5G. The recent Levelling Up White Paper re-affirmed the government’s aim for 5G coverage to be available to the majority of the population by 2027.20 The government is currently developing a new Wireless Infrastructure Strategy, which will set out a strategic framework for the development, deployment, and adoption of 5G and future networks in the UK over the next decade.21 Other steps have been taken in developing 5G policy:

- in early 2021, Ofcom auctioned off part of the 700MHz and 3.6-3.8GHz bands to the mobile network operators, which was a significant development for 5G rollout, increasing the available capacity

- in December 2021, Ofcom introduced the first iteration of coverage metrics for 5G, which was a major step towards beginning to understand the extent of 5G coverage

- the 5G Testbeds and Trials programme, which aims to explore the benefits and challenges of deploying 5G technologies, has continued to support projects trialling new 5G use cases.22

As 4G networks are reaching full maturity and 5G rollout is gaining pace, the mobile network operators have started planning the decommissioning of the 2G and 3G network. For example, BT/EE plan to phase customers off 3G by 2023. Government announced in December 2021 that mobile network operators have confirmed that they do not intend to offer 2G and 3G services beyond 2033.

Change in infrastructure over the past year

In 2021 UK 4G landmass coverage from at least one operator was 92 per cent, and 69 per cent for coverage from all operators (Figure 5). However, significant disparities between the nations persist (Figure 5). This is largely driven by the difference in coverage in urban and rural areas: coverage from all operators is near 100 per cent in urban areas, but for rural areas it is around 80 per cent.23

The number of premises with 5G coverage increased over 2021, with coverage available from at least one mobile network operator at around 50 per cent of UK premises.24 This was driven by the doubling of the number of 5G base stations across the UK, from around 3,000 in 2020 to more than 6,500 in 2021.25 However, as these base stations are primarily located in urban areas this only represents a small part of the UK landmass.26

However, 5G coverage in the UK has been rolled out on a non standalone basis. This consists of upgrading the access network to 5G but continuing to use the 4G core network. In contrast, standalone 5G requires the core network to also be upgraded. Non standalone 5G has some benefits for increased capacity and the recent increase in coverage has been driven by operators aiming to manage congestion on their networks in dense urban areas. But only standalone 5G will bring the full range of benefits, such as ultra low latency.27

5G coverage metrics are still not well defined. The use of different spectrum bands with greatly varying bandwidth and different antennae technologies deployed means that there is a large disparity in the potential 5G experience offered in different areas.28

Figure 5: There is now good coverage of the UK landmass by at least one operator, but coverage by all operators is much lower

Percentage of landmass covered by 4G

Source: Ofcom (2021) Connected Nations, Ofcom (2021) Connected Nations: Spring 2021

Assessment of progress

Government continues to make good progress on delivering nationwide mobile coverage. The Shared Rural Network agreement set the vision for 4G mobile connectivity across the country, and there is a clear, long term plan in place. However, this agreement must now be delivered. There is a long way to go to reach the government’s targets on partial and total not spots. And, while 5G coverage increased over the past year, government is still lacking a clear vision for the role this technology will take in the long term. The upcoming Wireless Infrastructure Strategy must address this.

- Taking a long term perspective: Yes. There is a long term strategy in place for 4G coverage but more is needed to provide long term clarity on the rollout and vision for 5G coverage.

- Clear goals and concrete plans to achieve them: There are clear goals for 4G coverage and plans to deliver them through the Shared Rural Network agreement. However, these are not yet in place for 5G. Ofcom, working with the mobile network operators, also needs to establish a common approach to reporting.

- Firm funding commitment: Yes. There is clear funding in place for the Shared Rural Network agreement from government and the private sector. Currently, the vast majority of funding for 5G comes from the private sector.

- Genuine commitment to change: Partly. On 4G coverage there is a clear commitment to change and positive steps have been taken over the past year. However, this is not yet the case for 5G.The government’s current target to provide 5G to the majority of the population by 2027 appears to be somewhat arbitrary and has already nearly been met.29 New targets should be based on a clear picture of the future connectivity needs of consumers and the economy, and how mobile networks need to evolve to meet them. The long term commercial and strategic value of 5G will be determined by whether it becomes more than just a faster version of 4G, and whether it provides solutions to pressing problems. Government is developing the Wireless Infrastructure Strategy to articulate a vision for 5G and introduce a new policy framework to encourage innovation, competition, and investment in 5G networks.

- Action on the ground: Partly. Good progress is being made in delivering the Shared Rural Network agreement and 4G coverage rates are already high. 5G coverage is increasing rapidly due to network competition, but coverage metrics are at an early stage of development. There is uncertainty about the future public benefits of 5G and the extent to which policy and/or regulatory interventions will be required to promote a faster, more widespread roll-out of networks.

Next steps in the second National Infrastructure Assessment

Challenge: The digital transformation of infrastructure

The Commission will consider how the digital transformation of infrastructure could deliver higher quality, lower cost, infrastructure services

Next Section: Energy

In 2021, government published critical strategies on reaching net zero and decarbonising heat and buildings. The strategies contained ambitious targets. However, concrete plans and detailed policies are still lacking. Over the past year, renewable energy has continued to be deployed at pace, but heat decarbonisation is lagging behind, and installations of energy efficiency measures in buildings remain low. Last year government committed to deploying engineered greenhouse gas removal technologies, and now needs to publish delivery and funding plans to support this.

Energy

In 2021, government published critical strategies on reaching net zero and decarbonising heat and buildings. The strategies contained ambitious targets. However, concrete plans and detailed policies are still lacking. Over the past year, renewable energy has continued to be deployed at pace, but heat decarbonisation is lagging behind, and installations of energy efficiency measures in buildings remain low. Last year government committed to deploying engineered greenhouse gas removal technologies, and now needs to publish delivery and funding plans to support this.

Gas prices have risen sharply in recent months and the war in Ukraine is likely to push up prices further. Gas prices affect the price of heating and of electricity, as gas is used to generate electricity. This will have significant effects for many households and businesses. Whilst less than 4 per cent of Britain’s gas is supplied by Russia, prices are set in wider markets where Russia plays a larger role.30 The most effective and immediate response Britain can take is to reduce the use of gas through increasing the deployment of renewable electricity and increasing the energy efficiency of buildings.

Government is facilitating rapid deployment of renewable electricity generation and has sound policy in place to continue this over the next decade. In 2020, renewable generation made up 43 per cent of total electricity supply.31

Government has long term targets for decarbonising heat and improving energy efficiency, but these are not supported by a delivery plan or clear funding. The challenge of reducing emissions from heat is now urgent.

In the Net Zero Strategy government has for the first time committed to deploying engineered greenhouse gas removal technologies and set an ambition in line with the Commission’s recommendation for deployment by 2030. But detailed policy must now be rapidly developed if this ambition is to be met.

Priority actions for 2022

Improve energy efficiency schemes to put England on track to deliver the government target for as many homes as possible to be EPC C rated or above by 2035

Publish a detailed plan to deliver at least the 5 MtCO2 per year of engineered removals by 2030 ambition in the Net Zero Strategy.

The energy sector

The energy sector covered by the Commission largely consists of two key networks: electricity and natural gas. It also includes new infrastructure networks and technologies that will be required to decarbonise the country, such as hydrogen and engineered greenhouse gas removals

The energy sector remains far too carbon intensive. Greenhouse gas emissions from the energy sector have reduced (figure 6), but this has been driven primarily by reducing emissions from electricity generation (figure 6). Further reductions and a move to a fully low carbon generation mix will be needed within the next 13 years to meet the UK’s decarbonisation targets. Emissions from electricity need to fall to near zero by 2035, and emissions from heat need to reduce by around 50 per cent by 2035 and to near zero by 2050 from 2019 levels.

The sector continues to provide a high quality and reliable service. While outages happen, the UK’s energy sector is one of the most reliable in the world, with comparatively few interruptions in supply that affect consumers, and these have been reducing over time.32 Incidents causing a loss of supply are rare. However, when they do happen, as after Storm Arwen in November 2021 and Storms Eunice and Franklin in 2022.They are a painful reminder of how essential a reliable supply of electricity is, and how important it is for the system to be resilient to such events and able to respond and recover quickly.

The Commission has set out a more detailed overview of the energy sector in Second National Infrastructure Assessment: Baseline Report Annex B: Energy and in the Commission’s data on sector performance.

Figure 6: Emission reductions have been driven by electricity in recent years

Actual and potential emissions in the government’s net zero delivery pathways (central estimate of upper and lower range used)

Source: Department for Business, Energy & Industrial Strategy (2021), Net Zero Strategy – charts and tables. Note: the figure uses 2019 emissions rather than 2020 emissions due to uncertainty around the short term impact the Covid-19 pandemic may have had on emissions.

Progress against the Commission’s recommendations

Electricity generation

Commission recommendations

In the first Assessment the Commission found that, over the long term, the UK could have a low cost and low carbon energy system, powered primarily by wind and solar.

The Commission recommended that government act to deliver 65 per cent of Britain’s electricity from renewables by 2030.33 To deliver this the Commission recommended that:

- contracts for difference auctions be used for the overwhelming majority of the increase in renewable capacity required, with government setting out indicative budgets and timelines

- contracts for difference auctions for onshore wind and solar should be reopened.

Increasing deployment of renewables will decrease reliance on natural gas for generating electricity. Alongside reducing emissions, this will reduce exposure to natural gas prices affected by Russian supplies.

In its Smart Power study, the Commission called on government to increase the flexibility of the electricity system by increasing electricity interconnection and facilitating increased deployment of storage and demand side response.34

The Commission proposed taking a one by one approach to deploying nuclear power stations beyond Hinkley Point C and recommended that government should not agree support for more than one additional nuclear plant before 2025. In September 2021, the Commission advised government that the sixth Carbon Budget did not result in a change to this advice. Other technologies can deliver an electricity system consistent with meeting the sixth Carbon Budget and these technologies are less risky than delivering more than one new nuclear plant by 2035.35 The timelines for deploying additional plants mean nuclear cannot play a short term role in reducing reliance on natural gas.

Government policy

In the National Infrastructure Strategy, government mostly endorsed the Commission’s recommendation to deliver 65 per cent renewable electricity by 2030 and in the Net Zero Strategy committed to a fully decarbonised power system by 2035, subject to security of supply.36 This follows on from previous announcements to target 40 GW of offshore wind (including 1 GW floating offshore wind) by 2030, and to reintroduce onshore wind and solar into the contracts for difference auctions.37 Government has also committed to hold annual contracts for difference auctions.38 The government is working on options to coordinate the buildout of a North Sea grid through the Offshore Transmission Network Review, which is a key enabler of offshore renewables.39

In 2021, the government and Ofgem published an updated Smart Systems and Flexibility Plan, which predicted that a tripling of low carbon flexibility capacity would be needed by 2030. The plan set out a number of actions to reduce barriers to deployment and committed to monitor the success of actions to increase flexibility through the flexibility monitoring framework.40 Government recently launched a call for evidence in 2021 on the role for large scale, long duration energy storage, recognising that is not currently attracting enough investment nor being built at sufficient scale.

The government is also making progress in bringing one new large scale nuclear project, beyond Hinkley Point C, to Final Investment Decision by the end of this Parliament, subject to it being good value for money and securing all relevant approvals. A decision was made in 2021 that new nuclear projects would be funded using a regulated asset base.41

Change in infrastructure over the past year

Renewables share of electricity generated increased to 43 per cent in 2020, up from 37 per cent in 2019.42 Despite generation capacity increasing since the end of 2020, the share of renewable generation over 2021 is likely to be lower due to low average wind speeds affecting the output of wind turbines. This highlights the importance of having a range of generation and storage technologies available to support security of the electricity supply. Interconnector capacity has increased from 4 GW in 2016 to 6 GW in 2021, and storage capacity has increased from 3 GW in 2016 to 4 GW in 2021.43

Figure 7: Renewable deployment is on track to deliver the Commission’s recommendation

(Left chart) Historic share of generation and Commission target 2010 – 2030 (Right chart) Rates of change 2010 to 2030

Source: Department for Business, Energy & Industrial Strategy (2021), Energy Trends: UK renewables Renewable electricity capacity and generation (ET 6.1 – quarterly).

Assessment of progress

Government is facilitating rapid deployment of renewable electricity generation and has ambitious commitments and concrete policy in place to continue this over the next decade. However, there is a significant delivery challenge ahead that must be overcome. In the last decade renewable electricity increased from around 7 per cent of total generation to 43 per cent, but over the next decade this needs to increase to over 65 per cent at a time when overall electricity demand is set to substantially increase.44 Successfully deploying more renewable electricity generation also creates new challenges for cost effectively balancing the system. Alternatives to using natural gas for balancing exist, but deployment needs to accelerate.

- Taking a long term perspective: Yes. Government has set a long term strategy with a focus on significantly increasing renewable capacity to deliver a decarbonised system by 2035, subject to security of supply. Government has also recognised the critical role of low carbon flexibility and the need to take action to significantly increase deployment.

- Clear goals and concrete plans to achieve them: Yes. Government has set a clear goal of a fully decarbonised electricity system by 2035, with generation capacity to be delivered mainly through contracts for difference auctions. It has committed to monitoring the success of its actions to increase the flexibility of the electricity system and adapting policy if necessary.45 However, the challenges of delivering these commitments are significant.

- Firm funding commitment: Yes. The contracts for difference scheme has given certainty to developers of renewable generation, and the current pipeline of planned low carbon generation underlines industry confidence in government funding. Government has committed £265 million to the next auction, to be completed in 2022.46 Additional funding may be needed to support deployment of flexibility solutions to ensure security of supply.

- Genuine commitment to change: Yes. The government has accepted the Commission’s recommendations of a highly renewable system, with security of supply delivered by flexibility. Some government goals for electrification in heat and surface transport are also reliant on a secure, low carbon electricity system, underlining this commitment.

- Action on the ground: Yes. Contracts for difference auctions continue to be used to deploy renewables at pace and the government is on track to reach the level of renewable deployment recommended by the Commission (Figure 7). Since the Commission published its Smart Power report, more flexible assets have been deployed. But delivery is a major challenge – renewable generation needs to increase significantly and the use of natural gas to provide flexibility needs to be largely replaced over the next decade.

Next steps in the second National Infrastructure Assessment

Challenge: Decarbonising electricity generation

The Commission will consider how a decarbonised, secure and flexible electricity system can be achieved by 2035 at low cost.

Heat and energy efficiency

Commission recommendations

In the first Assessment the Commission found that a low cost low carbon heating system could be delivered, but that there was significant uncertainty in the future costs and performance of heat pumps and hydrogen boilers. To address this, the Commission recommended running a trial to supply hydrogen to at least 10,000 homes by 2023 and establishing an evidence base on the performance and cost of installing heat pumps within the building stock.

Energy efficiency can reduce the cost of heating a home and increase options for low carbon heating. The Commission recommended that government set a target of 21,000 measures a week for installations of energy efficiency measures in England, with policies to support this including funding of £3.8 billion up to 2030 for improvements in social housing, trialling innovative approaches for driving energy efficiency in owner occupied homes, and tightening regulations and enforcement in the private rented sector.

Recent energy price rises have brought the cost of heating homes into stark focus. Consumer energy demand can be reduced through targeted energy efficiency improvements, and this becomes even more important in times when energy bills are increasing. The Commission’s recommendation sought to increase the rate of energy efficiency installations across homes, with government providing funding to support delivery to those in social housing.

Government policy

In October 2021 the government published a Heat and Buildings Strategy setting out plans to cut emissions from heating via a gradual transition which will start by driving down the cost of heat pumps and incentivising take up.47 It set an ambition to phase out the installation of natural gas boilers from 2035 and a commitment to install 600,000 heat pumps annually by 2028, primarily through:

- The Boiler Upgrade Scheme, which run from 2022-23 to 2024-25 and will offer £5,000 grants for low carbon heating systems up to a total value of £450 million for homeowners and residential landlords; government expects this to deliver around 30,000 heat pumps for each year it is running48

- a market based mechanism, currently out for consultation, to drive heat pump installations by placing an obligation on fossil fuel heating system manufacturers to achieve the sale of a certain level of heat pumps; government expects this to deliver between 210,000 and 330,000 heat pumps per year by 202849

- The Future Homes Standard, which will ensure that all English homes built after 2025 produce no operational carbon dioxide;50 government expects this to deliver around 200,000 heat pumps per year by 2028.51

In addition, the Heat and Buildings Strategy set out plans to make a strategic decision on the role of hydrogen in decarbonising heat in 2026.52

The government did not agree with the Commission’s recommendation to target 21,000 energy efficiency installations per week. It argued that a measures based target could lead to a focus on measures installed at the expense of the energy or emissions reduced. Government committed to developing a new metric that rewarded actual energy and carbon reductions for non-domestic buildings.53

Government’s current target is to upgrade as many homes as possible to a rating of Energy Performance Certificate (EPC) Band C by 2035.54 However, the government’s main energy efficiency and low carbon heating subsidy scheme – the Green Homes Grant Voucher Scheme – was closed to new applications in March 2021. Funding for local authority delivered schemes continues with £300 million of additional funding allocated.55 In the past year £800 million of funding has also been allocated to the social housing decarbonisation fund over the next three years, in line with the Commission’s recommendation.56 The government has also announced a further £950 million for the Home Upgrade Grant, a scheme to improve energy efficiency and install low carbon heating in fuel poor homes not connected to the gas grid.57

Change in infrastructure over the past year

Steps have been taken to establish the safety case for hydrogen for heat, with the Hy4Heat programme running full hydrogen boilers in purpose built unoccupied demonstration homes.58 A neighbourhood trial of hydrogen is due to start in 2023 with the H100 Fife Neighbourhood Trial, followed with a village trial by 2025.

Heat pumps have also been trialled and the evidence base on suitability for different property types is growing. The recent Electrification of Heat UK Demonstration Project has installed 742 heat pumps in a wide range of property types and will now monitor how they perform. Whilst the number of consumers installing a heat pump each year has been growing, UK heat pump sales remain very limited, at around 36,000 per year, in comparison with sales of fossil fuel boilers.59

The energy performance of the housing stock has been increasing in recent years. Survey data suggested that the proportion of homes rated EPC C or better has risen from 12 per cent in 2010 to 40 per cent in 2019.60 The rate of change saw a material dip in 2014 as a result of changes to government schemes to support the installation of energy efficiency measures.

Assessment of progress

Government has long term targets for decarbonising heat and improving energy efficiency, but these are not yet fully supported by a delivery plan or clear funding. The need to meet the Sixth Carbon Budget means that resolving the challenges in decarbonising heat are now urgent:

- Taking a long term perspective: Yes. Government is taking a long term perspective by committing to take a decision on the role of hydrogen in home heating by 2026, setting targets for 600,000 heat pump installations by 2028, phasing out natural gas boiler installations by 2035, and increasing the energy efficiency of buildings.

- Clear goals and concrete plans to achieve them: Partly. Detail on how long term targets will be delivered is still under development, including how government will address the major questions still to be answered on decarbonising heat. Government has delivered on its commitment to consult on moving to an approach which measures and rewards actual energy and carbon reductions.61

- Firm funding commitment: No. Government’s current strategy for decarbonising heat relies heavily on the cost of heat pumps and hydrogen falling rapidly. A significant proportion of the government target for heat pump deployment will need to be delivered through the government’s market mechanism, which may not deliver if the cost of heat pumps does not fall in line with the government’s stretching ambitions. Government has allocated short term funding to improve energy efficiency in social housing and low income households through their local authorities and is using regulation to support improvements in the private rented sector. There remains a lack of incentive to encourage improvements in energy efficiency by owner occupiers.

- Genuine commitment to change: Partly. The net zero target, and interim Carbon Budgets, make it clear that change is needed but without detailed plans to support this, it is not yet clear a genuine commitment has been made. There are unresolved areas government needs to address, including what heating technologies are feasible and where, how to create the right incentives for people to switch from fossil fuel heating, how much investment is required and who will pay for this, and how all of this will be delivered at pace.

- Action on the ground: Partly. Progress has been made on building the evidence base for heat pumps and hydrogen over 2021, but at scale trials of hydrogen for heating will come later than recommended and heat pumps trials are not yet delivering performance data. On energy efficiency, analysis from the Climate Change Committee suggests that if the government’s target for 2035 is to be met, the number of energy efficiency installations will need to increase significantly.62

Next steps in the second National Infrastructure Assessment

Challenge: Heat transition and energy efficiency

The Commission will identify a viable pathway for heat decarbonisation and set out recommendations for policies and funding to deliver net zero heat to all homes and businesses

New infrastructure networks

Commission recommendations

To meet the net zero target, new infrastructure networks will be required to remove greenhouse gases from the atmosphere and store them permanently underground.

In its recent study, Engineered Greenhouse Gas Removals, the Commission recommended that government commit to deploying a range of engineered removals technologies to remove between 5 and 10 MtCO2e per year by 2030, and publish in 2022 a detailed plan to support deployment.63 The Commission also recommended that government deliver sufficient carbon transport and storage networks to serve engineered greenhouse gas removals plants.

Government policy

In the Net Zero Strategy the government has, for the first time, committed to deploy engineered greenhouse gas removal technologies in the UK.64 Government set an ambition to use engineered removals to extract 5 MtCO2e from the atmosphere each year by 2030, reaching around 23 MtCO2e per year by 2035. Development of the detailed policy frameworks to support this is ongoing, with plans for consultations on potential business models and reforms to the UK emissions trading scheme planned.65 Progress is also being made on support for early stage engineered removals, with funding awarded to projects through a £70 million competition.66

At the same time, government has significantly increased its ambition on deploying carbon capture and storage networks. It is now aiming to deploy between 20 and 30 MtCO2e capacity by 2030.67 In the last year, government announced Hynet and the East Coast Cluster as the first two carbon capture and storage clusters to receive support.68

Assessment of progress

The Net Zero Strategy demonstrates positive ambition for engineered removals, but detailed policy must now be rapidly developed to turn this into a genuine commitment to delivering at scale engineered removals in the UK.

- Taking a long term perspective: Yes. Government has begun to set out long term targets for engineered removals deployment and now needs to consult on how it will support the sector to deliver what is needed to meet its ambition for 2030 and beyond.

- Clear goals and concrete plans to achieve them: No. While government has committed to consulting on business models, a comprehensive and detailed plan for delivering engineered removals is needed before the end of 2022.69

- Firm funding commitment: Partly. Developing policy for who will pay for engineered removals will be essential to enable their deployment, however the proposed consultation on the role of the UK emissions trading scheme (where funding will come from polluters) is already behind schedule.

- Genuine commitment to change: Yes. In the Net Zero Strategy the government has, for the first time, committed to deploy engineered greenhouse gas removal technologies in the UK. Government now needs to set out delivery and funding plans to deliver this commitment.

- Action on the ground: Not applicable. Greenhouse gas removals are a nascent technology and there is no relevant delivery on the ground to discuss in the context of the Commission’s current recommendations.

Next steps in the second National Infrastructure Assessment

Challenge: Networks for hydrogen and carbon capture and storage

The Commission will assess the hydrogen and carbon capture and storage required across the economy, and the policy and funding frameworks needed to deliver it over the next 10 to 30 years.

Flood resilience

More than five million homes and properties in England are at risk of flooding,70 and climate change means the risk is growing.71 Government has started to act. National policies have been strengthened and investment has doubled. But government has yet to specify long term targets for flood resilience.

There have been positive changes in flood resilience policy since the first National Infrastructure Assessment was published. In line with the Commission’s recommendations, government investment in flood defences has doubled and policies have been revised to emphasise catchment based planning, green infrastructure, and property level resilience. But government has yet to define long term targets for flood resilience. Until it does so, policies and investment are unlikely to fully address the flood risk challenges the Commission identified in the first Assessment.

Priority action for 2022

Set out a long term measurable objective for what flood resilience policy in England is trying to achieve.

The flood resilience sector

In 2020, more than five million properties in England were at risk of flooding,72 although the level of risk differs by area. Around 2.5 million properties are at risk of flooding from rivers and the sea and around 3.2 million at risk from flooding from surface water.73 Over 65 per cent of properties in England are served by infrastructure located in areas at risk of flooding, although this does not account for existing flood resilience measures at infrastructure asset sites.74

Lack of data makes it challenging to assess the overall performance of the flood resilience sector.75 Central government spending on flood risk management is around £15 per household per year, and capital investment around £19 per household per year.76 There is some evidence that flood risk management has led to improvements in the quality and quantity of habitats, but it is hard to understand the scale of these impacts.77

Currently, there is no comprehensive way to measure whether the level of flood resilience in England has improved over past years. The Environment Agency uses the number of properties ‘better protected’ as a key indicator of flood risk management investment outcomes. ‘Better protected’ means that homes have been moved to a lower risk category through improved flood risk management.78 The government’s investment between 2015 and 2021, which equated to £2.6 billion, improved protection for over 300,000 homes.79 Although this is an easy to understand measure of performance, it does not provide a good view of overall progress in tackling flood risk. This is because it does not account for better protection of businesses or infrastructure. Furthermore, it does not account for reduced levels of protection due to deterioration of flood protection assets or the increased risk of flooding due to climate change.80

The Commission has set out a more detailed overview of the floods sector Second National Infrastructure Assessment: Baseline Report Annex C: Flood Resilience and the Commission’s data on the performance of the sector.

Progress against the Commission’s recommendations

Commission recommendations

In previous decades, flood resilience policy in England has too often been reactive and piecemeal in nature, with unclear objectives and stop start funding cycles.

In the first Assessment, the Commission recommended that government introduce a national flood resilience standard, such that by 2050 all communities would be resilient to flooding events with annual likelihood of 0.5 per cent (one in 200 years). In densely populated areas, where the costs per household of providing defences are lower, the Commission proposed a higher standard of resilience against flood events with annual likelihood of 0.1 per cent (one in 1,000 years).81 These standards would provide focus for risk management authorities and enable clearer monitoring of local and national progress. To deliver this, the Commission recommended that government put in place a rolling six year funding programme. There is a strong case for government to set multiyear investment programmes to avoid a return to reactive funding, where budgets are reduced only to increase again following flood events.

To support the development of a long term strategy the Commission also recommended that:

- the Environment Agency should update plans for catchments and coastal cells by the end of 2023

- new developments should be resilient to flooding and not increase risk elsewhere

- water companies and local authorities should work together to publish joint plans to manage surface water flood risk by 2022.82

Government policy

In the Flood and coastal erosion risk management: policy statement, the government set out how it plans to make the nation more resilient to floods, including delivering nationwide resilience, using green and grey infrastructure, and delivering resilience measures at the property level, as recommended by the Commission.83

However, government did not set national standards of flooding resilience, or a clear long term objective for what it is trying to achieve. The government argued that developing national standards would be complicated and resource intensive, and that differing levels of current flood resilience require a more tailored local approach. Instead, it committed to developing a national set of flood resilience indicators that will enable better monitoring of changes in flood resilience over time.84 Work by the Environment Agency to develop those indicators is ongoing, and due to be complete in spring 2022.85

The government will also invest £5.2 billion in flood and coastal defences between 2021 and 2027. This investment aims to ‘better protect’ 336,000 properties by 2027.86

In addition, further progress has been made in developing the detail of government’s policy approach in the last year:

- the government concluded a call for evidence on ways it could take account of local circumstances when allocating investment, and announced that it will launch a consultation on options to achieve this87

- theEnvironment Agency published the initial list of flood and coastal erosion risk management schemes it plans to take forward under the 2021 to 2027 funding settlement88 and planned to invest £860 million on the design and construction of more than 1,000 schemes in 2021-2289

- the government published its review of planning policy for development in flood risk areas90 and committed to issuing local planning authorities with guidance on their duties and on using developer contributions for flood resilience schemes.91

Assessment of progress

Over the past year, progress in developing policy to address the challenge of flooding in the UK has been slow. Allocating £5.2 billion in funding over the next six years was a positive first step, but without clear targets for flood resilience and long term plans to deliver them, the government is unlikely to deliver nationwide resilience to flooding by 2050. It should therefore set out the level of flood resilience it wishes to achieve through to 2050, and clarity on the long term funding to deliver this. The new flood resilience indicators, due to be published in the coming months, could provide the basis for setting such targets and for measuring performance against them.

- Taking a long term perspective: No. Government has not set out either targets orinvestment plans for flood resilience beyond 2o27, as the Commission recommended.

- Clear goals and concrete plans to achieve them: No. Government has set itself a goal of ‘better protecting’ 336,000 properties by 2027, although this measure does not reflect the number of properties that may have less protection each year due to flood asset deterioration or climate change. Government does not have any measurable, long term objectives for flood resilience beyond 2027. The new flood resilience indicators could provide a rigorous basis for assessing whether its policies and investment are delivering better resilience for communities across the country.

- Firm funding commitment:Yes. Government has allocated £5.2 billion for the next six years to flood and costal defences, which represents a doubling of investment over the previous six year period. This will provide risk management authorities with clarity on funding and enable better forward planning of investment.

- Genuine commitment to change: No. Until government sets out long term plans to maintain and improve nationwide flood resilience by 2050 its actions will not constitute a genuine commitment to change.

- Action on the ground:Not applicable. The Environment Agency continues to deliver flood resilience schemes, with initial design and construction work on more than 1,000 schemes due to start in 2021-22.92 As the first full financial year of the government’s new 2021 to 2027 investment plan has not yet concluded, it is too soon to assess progress against delivery.

Next steps in the second National Infrastructure Assessment

Challenge: Surface water management

The Commission will consider actions to maximise short term opportunities and improve long term planning, funding and governance arrangements for surface water management, while protecting water from pollution from drainage. The Commission will deliver this as a separate study and report to government by November 2022, in advance of its other recommendations.

Next Section: Water

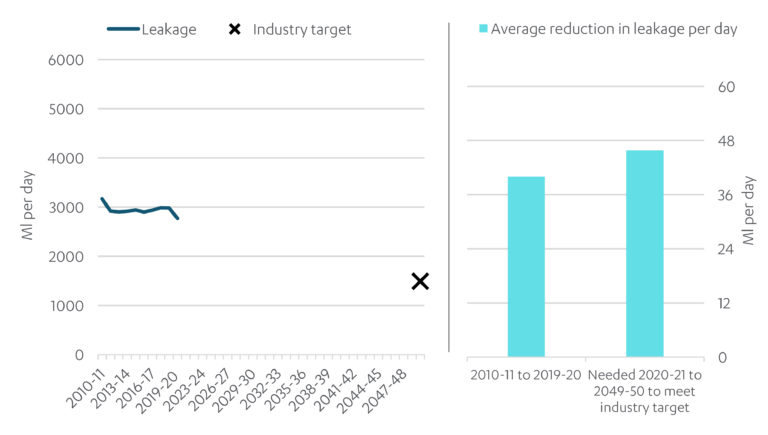

Additional capacity is needed to avert the real and growing risk of water shortages. Plans for additional supply infrastructure are advancing and there is some evidence that leakage is falling, although it is too soon to see a sustained trend. But per capita consumption is not yet falling, and stronger policies may be needed to address this.

Water

Additional capacity is needed to avert the real and growing risk of water shortages. Plans for additional supply infrastructure are advancing and there is some evidence that leakage is falling, although it is too soon to see a sustained trend. But per capita consumption is not yet falling, and stronger policies may be needed to address this.

In the first National Infrastructure Assessment, the Commission proposed addressing the growing risk of water shortages through a ‘twin track’ approach: increasing supply, while reducing demand. To deliver this, the Commission called for the creation of additional supply and a national water transfer network, ambitious targets for leakage reduction, and compulsory metering, requiring companies to consider systematic roll out of smart meters to drive down water consumption.

There is now some early evidence that government, regulators, and industry are making progress on developing new supply infrastructure and on reducing leakage. But per capita consumption, already at unsustainable levels, is not yet falling. The sector has set ambitious targets, and published draft regional plans for future water resources, but it is not clear whether the government’s new policies will support the reductions needed.

Priority action for 2022

Strengthen and progress plans for reducing per capita water consumption to deliver the targeted 110 litres per person per day by 2050

The water sector

The water sector delivers water of reliable quality to homes and businesses across the country. Significant drinking water quality incidents are rare,93 and unplanned interruptions to water supply have fallen by one third since 2012.94 However, over the coming decades the UK faces a real and growing risk of water shortages, especially in the south east of England.95