Infrastructure Progress Review 2023

Published:

Our latest annual assessment of the government's progress on implementing its commitments on infrastructure.

Foreword

The task of this annual review is to assess progress towards implementation of the Commission’s past recommendations adopted by government.

In doing so it would be remiss not to take a wider view on progress towards major infrastructure objectives government has set itself, and behind which there is broad political consensus – such as creating a net zero economy by 2050 and promoting economic growth across all regions of the UK.

These goals require huge public and private investment over a sustained period.

During 2022 there were some steps forward: greater devolution to West Midlands and Greater Manchester to implement their own ambitious infrastructure strategies, and progress to keep the UK on track to achieve nationwide coverage of gigabit broadband by 2030.

But if the Commission saw 2021 as a year of slow progress in many areas, in 2022 movement has stuttered further just as the need for acceleration has heightened. There have been negligible advances in improving the energy efficiency of UK homes, the installation of low carbon heating solutions or securing a sustainable balance of water supply and demand.

The risk of a mixed scorecard is that readers take their pick based on their own experiences or purposes. Residents in the north of England, for instance, could hardly be blamed for focusing on the appalling state of current rail services within and between the places pivotal to supporting growth. Others will cheer the further expansion of cheap renewable energy generation at a time of severe concerns about energy security and the high costs of fossil fuels.

But taking a strategic view on the recent pace of planning and delivery suggests a significant gap between long term ambition and current performance. To get back on track, we need a change of gear in infrastructure policy.

This means fewer low stakes incremental changes and instead placing some bigger strategic bets, backed by public funding where necessary – after all, the risk of delay in addressing climate change is now greater than the risk of over correction. We must have the staying power to stick to long-term plans, to spare cost increases that come with a stop-start approach and to give investors greater confidence in the UK. We must also accelerate and expand the devolution of power and funding to local leaders, who are best placed to identify their infrastructure needs and economic opportunities.

Getting our infrastructure right for the second half of this century is a journey that, by definition, will go on being plotted over the coming decades. But a further year of prevarication risks losing momentum on critical areas like achieving the statutory net zero target. Rarely has the need for speed been more evident.

Sir John Armitt, Chair

Next Section: Executive summary

Government has ambitious goals for infrastructure, but in many areas, it is not delivering fast enough. The United Kingdom faces long term challenges, from slow economic growth to delivering net zero. To meet these, government needs a long term infrastructure policy that it consistently delivers on. This document sets out a detailed review of progress over the last year against the Commission’s previous recommendations.

Executive summary

Government has ambitious goals for infrastructure, but in many areas, it is not delivering fast enough. The United Kingdom faces long term challenges, from slow economic growth to delivering net zero. To meet these, government needs a long term infrastructure policy that it consistently delivers on. This document sets out a detailed review of progress over the last year against the Commission’s previous recommendations.

The UK economy faces long term challenges. Economic growth in the UK economy has slowed in recent decades. Despite positive progress, much more action is needed to tackle climate change. Economic infrastructure can play a key role in overcoming these challenges. Effective infrastructure can support growth in the economy by cutting costs and better connecting people and places. Decarbonising key sectors such as power, heat, and transport is critical to meeting climate targets; around two thirds of the country’s greenhouse gas emissions come from economic infrastructure.

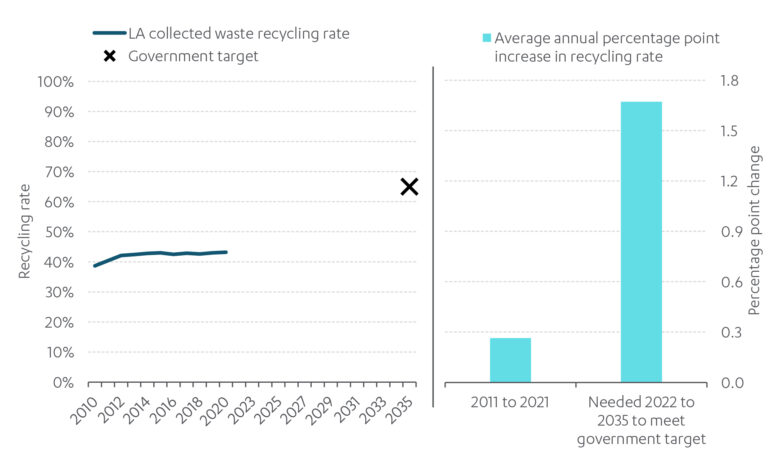

Government’s progress on implementing the Commission’s recommendations this year has been too slow. Positive progress has been made in rolling out gigabit broadband, increasing the amount of renewable electricity generation, continuing to implement further devolution, and developing plans to increase water supply. But in a range of other areas government is off track to meet its targets and ambitions: more uncertainty has been created around the timeline for delivering High Speed 2, energy efficiency installations are too low, comprehensive policy is not in place to meet the government’s target on decarbonising heating, the National Policy Statements for energy have still not been updated, recycling rates continue to plateau, and per person water consumption remains too high.

To get back on track the Commission recommends government embed four key principles in its policy making over the next year:

- develop staying power to achieve long term goals

- fewer, but bigger and better interventions from central government

- devolve funding and decision making to local areas

- remove barriers to delivery on the ground.

The country faces economic challenges

Slow growth of the country’s economy has been a persistent issue in recent decades. The UK’s average annual growth in Gross Domestic Product since the 2007-2008 financial crisis has been one per cent, compared to 2.5 per cent in previous decades.1 Since the early 2000s, UK productivity has fallen further behind comparator countries such as France, Germany, and the United States.2 Alongside this, the UK economy also continues to suffer from profound and persistent regional inequalities.3 London is the only major city in the UK that has above average productivity.4 Although even in London, productivity growth has slowed significantly since the financial crash.5

Part of the reason for the UK’s slow growth is low levels of investment.6 Since 1980, the UK has invested, as a share of Gross Domestic Product, less than comparator countries such as France, Germany, and the United States.7 Ambitious and stable policy from government, alongside effective regulation, is needed to facilitate private sector investment in the country’s key infrastructure sectors. Improving governance structures by enhancing devolution and removing barriers in the planning system will ensure increased investment is spent wisely and quickly.

Low levels of investment are also a challenge for reaching net zero. To meet its legally binding climate targets, the UK must reduce its overall greenhouse gas emissions by 78 per cent compared to 1990 levels by 2035, and to net zero by 2050. This will require significant investment across a whole range of activities, from heating homes to driving cars. Doing so will also help keep the UK at the forefront of international competition in some areas. Over 130 countries, comprising over 90 per cent of global gross domestic product, now have a net zero target set or under discussion.8

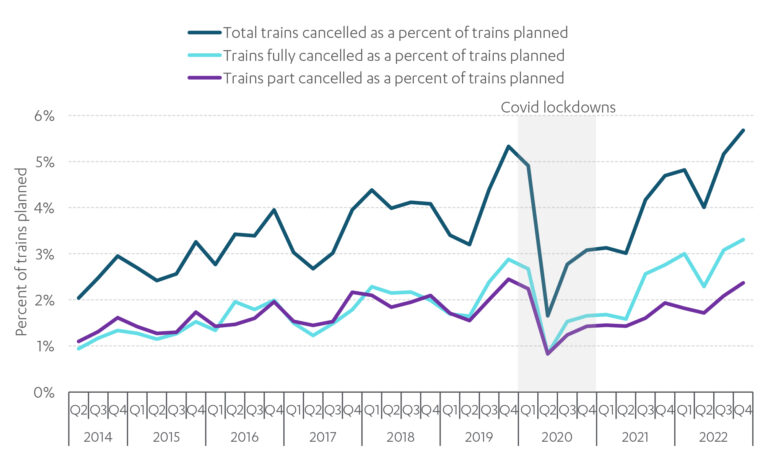

Recent years have also demonstrated the challenges of underinvestment in resilience. Heatwaves in 2022 exposed fragility in the UK’s water resources, and labour shortages and extreme weather events have disrupted the rail network. Many of these risks will become more severe in the face of a changing climate, and action to enhance resilience is becoming more pressing.

Infrastructure is a key part of the solution

Good infrastructure facilitates growth.9 Improving the quantity and quality of infrastructure services will lower costs for households and firms in the medium to long term. Transport and digital infrastructure support efficient housing and labour markets, allowing people to live and work in different locations.10 And infrastructure also directly enables productivity enhancing technological change, for example better mobile and broadband networks were critical for the emergence of new online services. Tackling long standing regional economic disparities will also require increased investment in infrastructure.11

Moreover, large scale investment in infrastructure, both public and private, is essential to achieving a net zero economy. In the UK, climate change is primarily an economic infrastructure challenge, with two thirds of emissions coming from the six sectors in the Commission’s remit. Estimates from the Climate Change Committee suggest up to £50 billion of investment will be needed each year for the next 25 years for the UK to reach net zero.12 Further investment will also be needed to increase resilience and adapt to the growing risks from flooding and drought driven by climate change.

Ambitious long term targets

In 2018 the Commission published the first National Infrastructure Assessment. This identified the country’s long term infrastructure needs and set out a series of actions for the government to take to secure the required investment. The Commission has followed the National Infrastructure Assessment with other studies containing recommendations across many infrastructure challenges.

The National Infrastructure Strategy, published in 2021, is a detailed and comprehensive approach to infrastructure policy responding to the Commission’s Assessment. It set out a series of policy decisions intended to support growth and put the UK on the path to a net zero economy. The Strategy was intended to endure, aiming to tackle entrenched policy challenges with a long term approach. As HM Treasury argue: “stronger economic growth requires a long term plan and commitment to see it through – there are no quick fixes to the challenges the UK faces.”13

The government has built on the National Infrastructure Strategy with other key strategies and has now set clear long term goals in many critical areas. The Net Zero strategy was published in 2021, the Environment Act was passed in 2021, and the Levelling Up White Paper and subsequent Bill set out a series of key missions to deliver over the next decade.

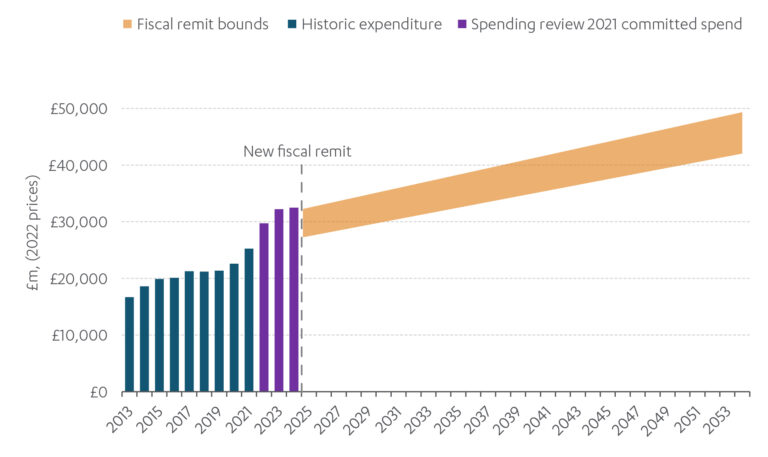

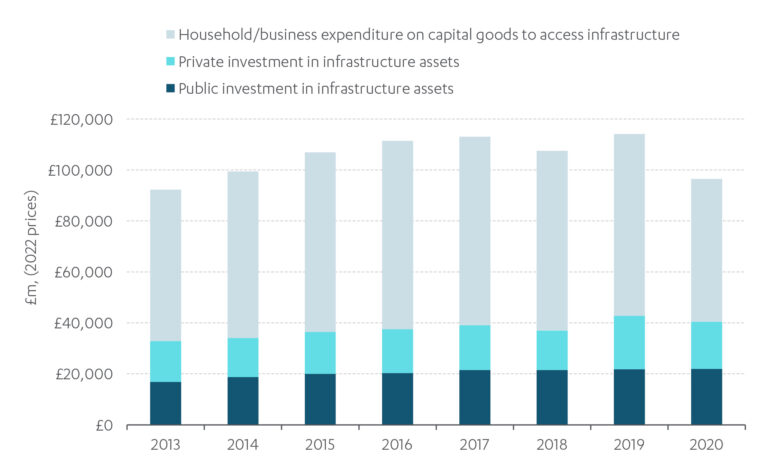

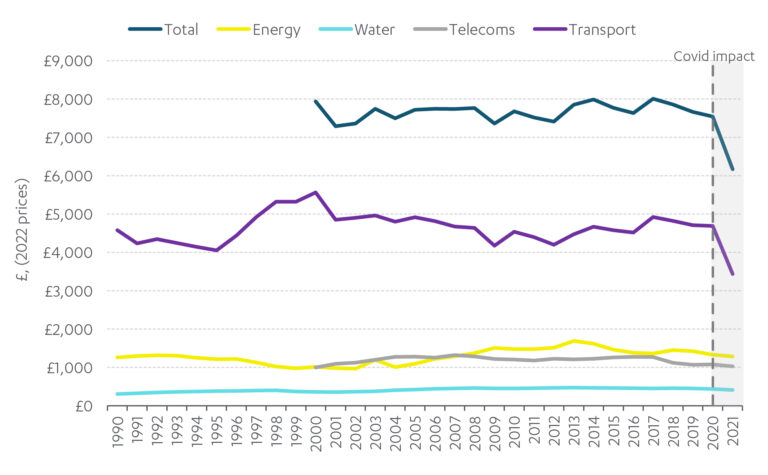

At the 2021 Spending Review, the government backed these high level ambitions with a funding commitment of £100 billion to support economic infrastructure from 2022-23 to 2024-25. This was re affirmed at the 2022 Spending Review (figure 1). However, over the last two decades government has frequently under delivered on spending commitments; it is critical this time that it follows through.14 The government has signalled a longer term commitment to investing in economic infrastructure by increasing the Commission’s fiscal remit, the technical guidance on how much public investment the Commission can recommend, to 1.1 – 1.3 per cent of GDP each year from 2025 to 2055 (figure 1).

Figure 1: Government is increasing spending on infrastructure in the short term, this must continue in the long term

Historic public expenditure on economic infrastructure 2013 to 2021, spending review commitments, and the Commission’s fiscal remit15

Source: Commission calculations, HMT Public Expenditure Statistical Analyses (2022)

Note: Spending review 2021 committed spend of £100 billion is profiled based on department capital budgets set out in Office for Budget Responsibility’s March 2023 economic and fiscal outlook.

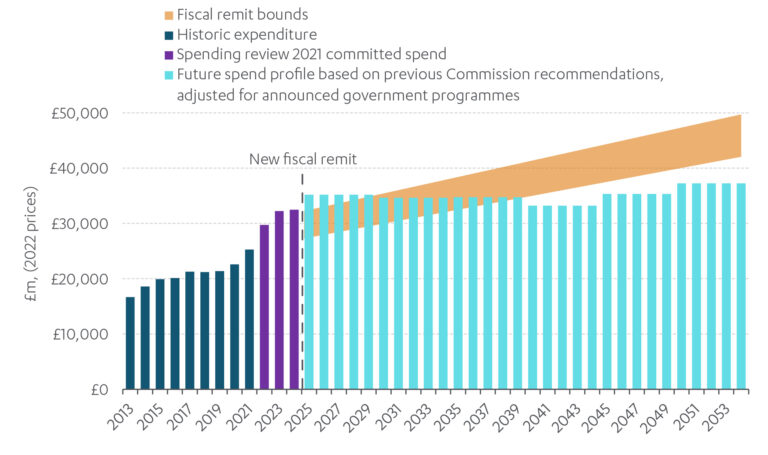

Private sector investment is also critical for meeting the government’s long term targets on infrastructure. In recent years, public and private investment in economic infrastructure assets has been broadly similar, with annual public investment around £20 billion and private sector investment around £18 billion (figure 2). The UK must remain an internationally competitive place to invest, at a time when the Inflation Reduction Act in the United States and the REPowerEU plan and Net-Zero Industry Act in the European Union make the investment environment more challenging. Ambitious and stable policy from government, alongside effective regulation, is critical for providing the private sector with the certainty it needs to invest.

Figure 2: Public and private sector investment in infrastructure assets is broadly equal

Public and private sector investment in infrastructure assets, 2013 to 202016

Source: Commission calculations

More consistent delivery from government is needed

The elements needed for successful delivery of the Commission’s recommendations and government’s ambitions are not currently all in place. Progress is being made. But significantly more action is needed to meet the Sixth Carbon Budget; carbon emissions need to fall from 447 MtCO2e in 2021 to 190 MtCO2e by 2035. Progress on delivering the ambitions set out in the Levelling Up White Paper is currently too slow. And barriers on the ground, such as the planning system, are slowing deployment across the board.

More detail on the Commission’s review of progress against its recommendations and government’s commitments in each of the key sectors within its remit is summarised below.

Digital

The government has made a genuine commitment to improve digital connectivity across the country. Delivery of gigabit capable broadband networks is progressing rapidly and, in 2022, gigabit capable coverage was extended to over 70 per cent of premises. This reflects significant increased investment from operators in recent years. If operators deliver on their published plans, and government maintains the £5 billion subsidy programme for under served areas, government will likely achieve its target to deliver nationwide coverage by 2030.

On mobile, 4G coverage from at least one operator now extends to around 92 per cent of the UK landmass, and the Shared Rural Network agreement should increase this to 95 per cent by 2026. However, challenges remain on securing investment for upgrading coverage on the rail networks.

Government must now set out a clear vision for 5G mobile networks in the upcoming Wireless Infrastructure Strategy. The long term commercial and strategic value of 5G will be determined by whether it becomes more than just a faster version of 4G, and whether it provides solutions to pressing problems.

Transport

The Commission has consistently recommended that local areas be given long term funding settlements for transport to aid planning and have greater control over investment. Moving away from the damaging system of competitive bidding for grant funding that erodes local capacity is critical.

Some progress has been made over the last year, including taking forward the commitment from the Levelling Up White Paper to transfer new powers, funding, and responsibilities to City Regions. The trailblazer deals and single multi year budgets announced for Greater Manchester and West Midland Combined Authorities are exemplars. The commitment to provide a second five year funding deal for England’s largest Mayoral City Combined Authorities for 2027-28 to 2031-32 will support long term planning. However, devolution must stretch across the whole country not just to major city regions. Progress empowering local authorities and helping them build capacity and capability must continue.

The government has committed to supporting the West Yorkshire Combined Authority to plan and build a mass transit system at an indicative cost of around £2 billion. While this is positive, it falls short of the ambition for major urban transport investment the Commission set out in the National Infrastructure Assessment.

Progress on major transport projects connecting major cities is mixed. The Integrated Rail Plan provided clarity with a long term plan for rail in the North and Midlands. It included a commitment to invest £96 billion to build new high speed lines and upgrade and electrify existing lines. Recent delays to delivery of High Speed 2 will inevitably delay the benefits of greater connectivity that are crucial to the economies of the North and Midlands – government must act to create a greater sense of certainty around the whole project and ensure that there are no delays to the current timetable for High Speed 2 services reaching Manchester. Action on the Cambridge-Milton-Keynes-Oxford arc remains slow and the government’s long term commitment to the road infrastructure needed to unlock growth in the region is unclear. If this does not change, the country will miss a significant growth opportunity.

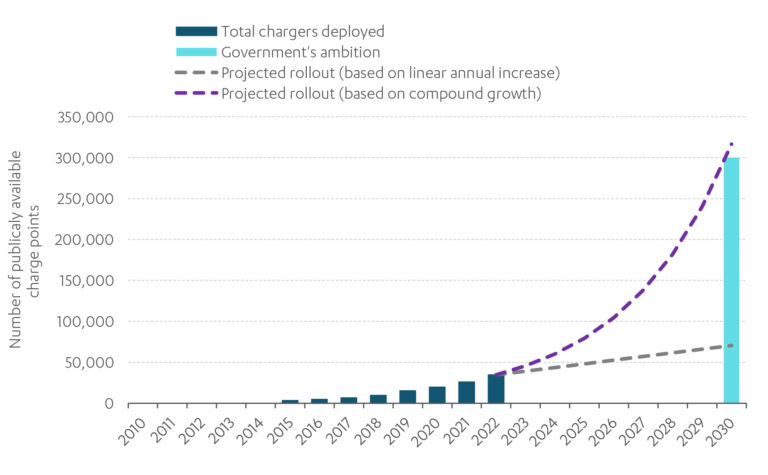

Transport remains far too carbon intensive. In 2021, emissions from surface transport were 101 MtCO2e. This needs to fall to around 30 MtCO2e by 2035 to meet the Sixth Carbon Budget. In 2022, government published critical strategies on decarbonising road transport, which support the government’s expectation of 300,000 public charge points and near 100 per cent electric car and van sales by 2030. But only 37,000 public charge points are currently installed. There are just eight years left to meet government’s target; a rapid increase in electric vehicle charge point installations is now needed to support the adoption of zero emissions vehicles.

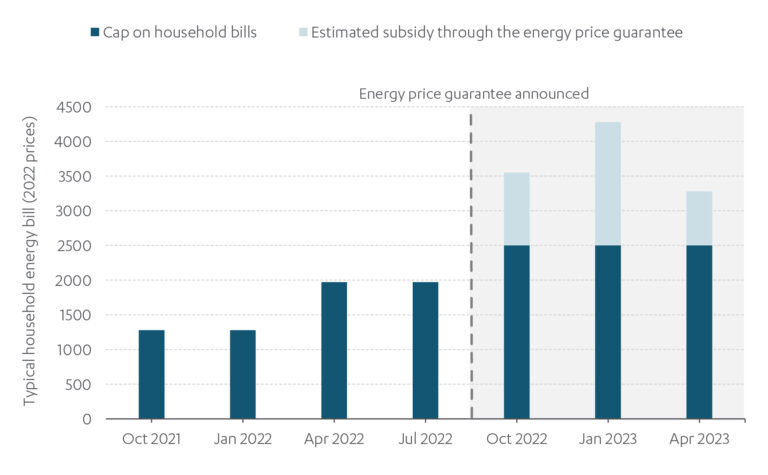

Energy

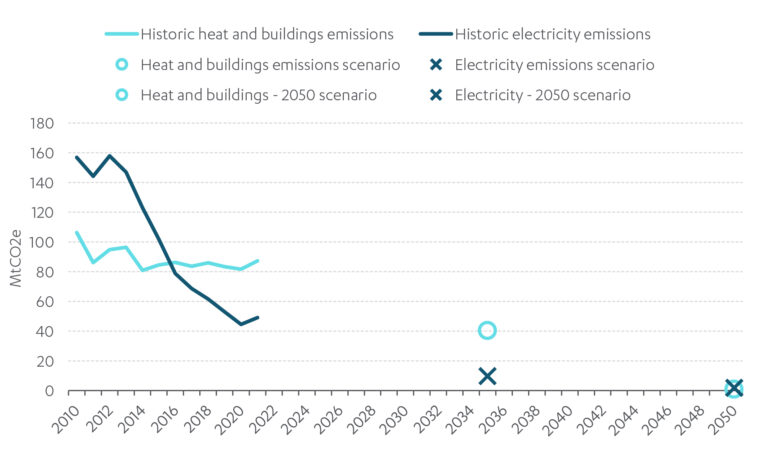

The UK is too reliant on natural gas: a high cost, high carbon, and insecure source of energy. In 2022, the sharp rise in gas prices prompted by Russia’s invasion of Ukraine increased the cost of energy and jeopardised security of supply. The government is now directly subsidising the energy consumption of households and businesses, setting prices for the average household at £2,500 per year between October 2022 and June 2023. Relying on natural gas for electricity and heating leaves the energy system far too carbon intensive. In 2021, emissions from the power and heating system were 135 MtCO2e, this needs to fall to around 50 MtCO2e by 2035.

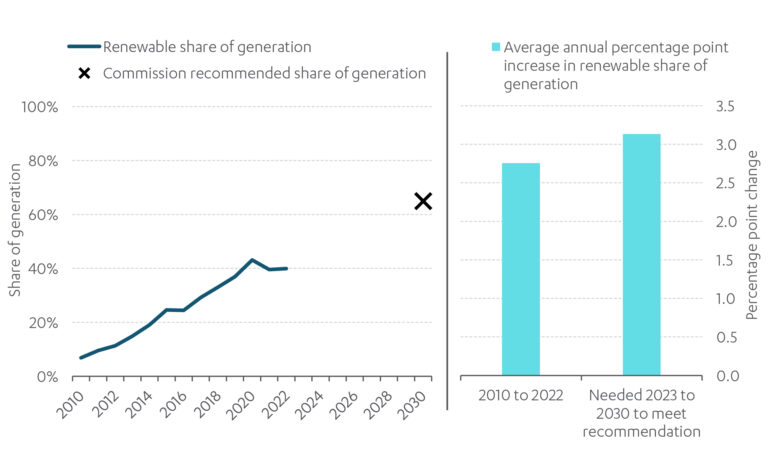

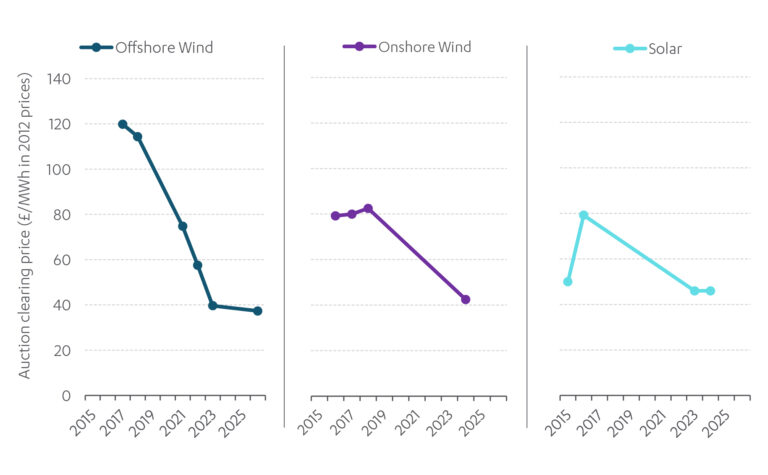

The Commission recommended that the UK should have a highly renewable electricity system, and good progress continues to be made delivering this. In 2022, 40 per cent of electricity was generated by renewables, up from around ten per cent a decade earlier. This has been driven by the government maintaining its contracts for difference policy, which provides revenue certainty and de risks investment. Renewable electricity, through offshore wind, onshore wind and solar, is now cheaper than producing electricity with natural gas. However, there are only 12 years to realise the government’s aim of a decarbonised electricity system by 2035. Barriers to further renewables deployment, such as securing transmission grid connections, must urgently be addressed to stay on track.

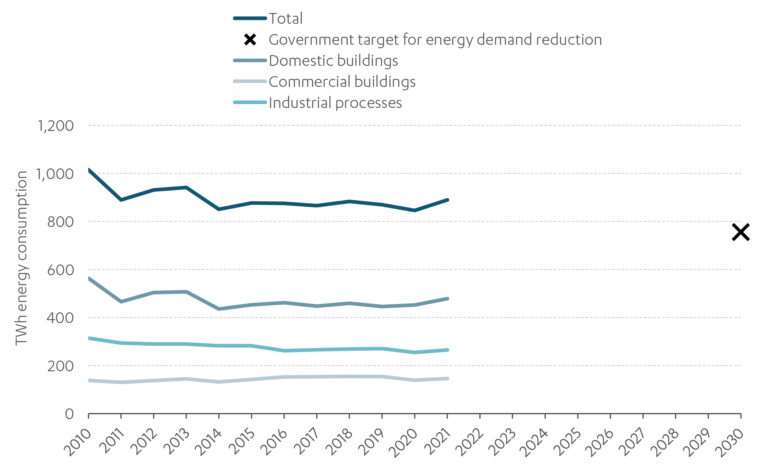

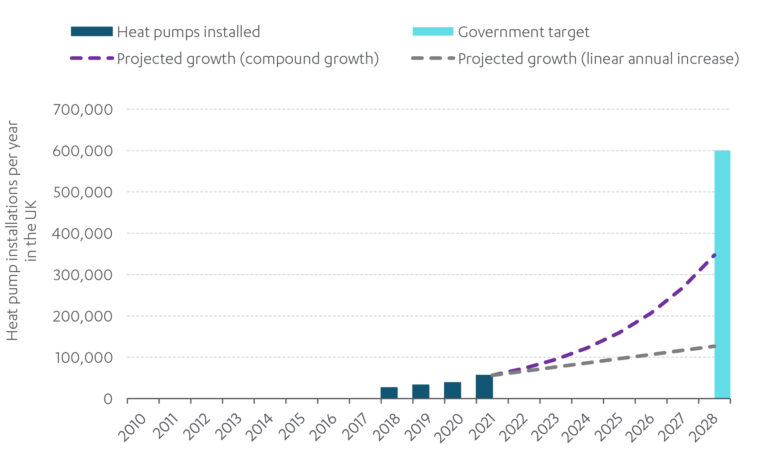

Little progress has been made on energy efficiency or heat this year. A concrete plan for delivering energy efficiency improvements is required, with a particular focus on driving action in homes and facilitating the investment needed. And while the government has set targets for decarbonising heating, these are not backed up by policies of sufficient scale to deliver the desired outcomes. Key policies remain missing, and government funding is insufficient to deliver the required change. In 2021, over 1.5 million gas boilers were installed. The government has set an ambition for at least 600,000 heat pumps to be installed each year by 2028, but only around 55,000 were installed in 2021. Unless the growth rate of installations increases significantly , the 600,000 heat pump installation target will be missed. These challenges must be urgently resolved to meet the Sixth Carbon Budget.

Flood resilience

Around two million homes and properties in England are in areas at risk of flooding from rivers and the sea, and climate change means the risk is growing. In line with the Commission’s recommendations, government investment in measures to reduce the risk of flooding has doubled and policies have been revised to emphasise catchment based planning, green infrastructure, and property level resilience. But government has yet to specify measurable long term targets for flood resilience. Until it does so, policies and investment are unlikely to fully address the flood risk challenges the Commission identified in the first Assessment.

Last year, the Commission published a study on surface water flooding. Over three million properties are currently at risk of suffering surface water flooding, and 325,000 are at high risk with at least a 1 in 30 chance of flooding every year. In the coming decades the number of properties in areas that are high risk could increase by up to 295,000, due to growing risks from climate change, new developments increasing pressure on drainage systems and the spread of impermeable surfaces from paving over gardens. The report sets out the need to better identify the places most at risk and reduce the number of properties at risk. This will mean devolving funding to local areas at the highest risk and supporting them to make long term strategies to meet local targets for risk reduction. The Commission expects government to respond to these recommendations this year.

Water

The drought of summer 2022 demonstrated the risk of water shortages due to climate change and population growth. In the first National Infrastructure Assessment, the Commission recommended addressing the growing risk of water shortages through a ‘twin track’ approach: to reduce demand and increase supply. To deliver this, the Commission called for ambitious targets for leakage reduction, compulsory smart metering, the creation of additional supply and a national water transfer network.

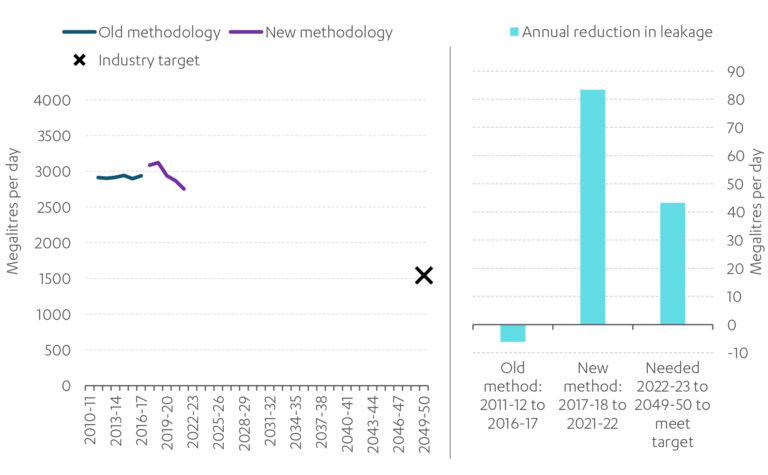

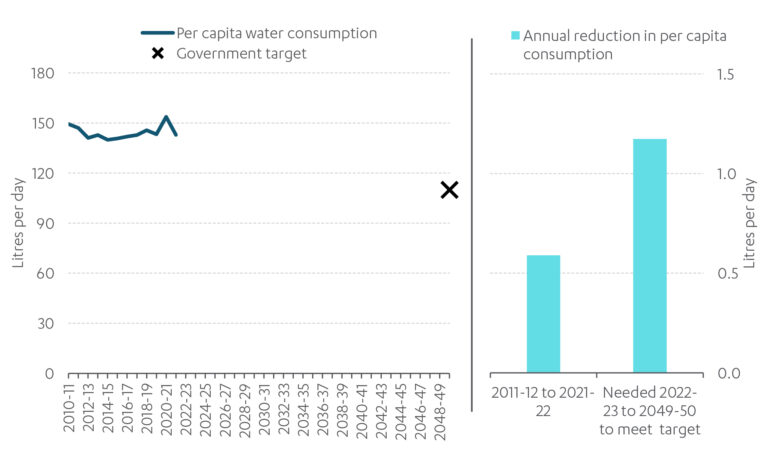

If implemented, industry plans are ambitious enough in scale to meet the Commission’s recommendations on leakage and new supply. And some progress has already been made, with leakage rates have fallen from around 3085 mega litres per day in 2017-18 to 2755 mega litres per day in 2021-22. However, there is still a long way to go to meet the target of reducing leakage by 50 per cent by 2050. To meet ambitions on supply, current plans suggest that at least 12 nationally significant infrastructure projects will need to be consented by 2030, so it is critical the planning system is fit for purpose and progress is made rapidly.17 Longer term demand reduction is dependent on government action, and it is not clear that current government policies on water efficient homes and water efficient product labelling are sufficient to achieve the 110 litres per person per day consumption target by 2050.

Waste

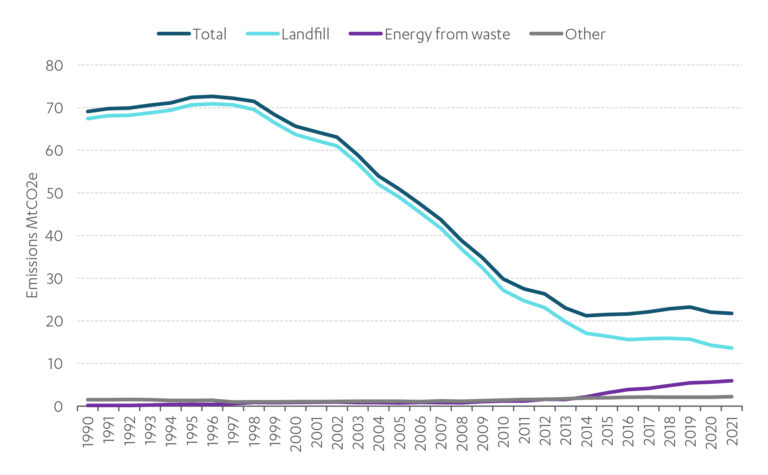

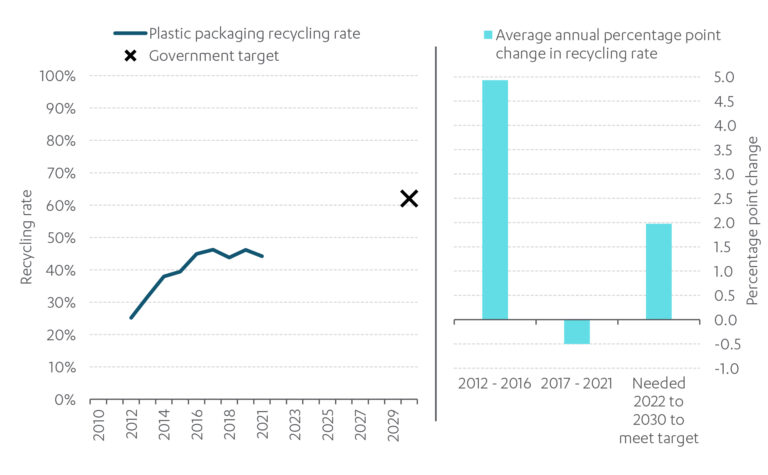

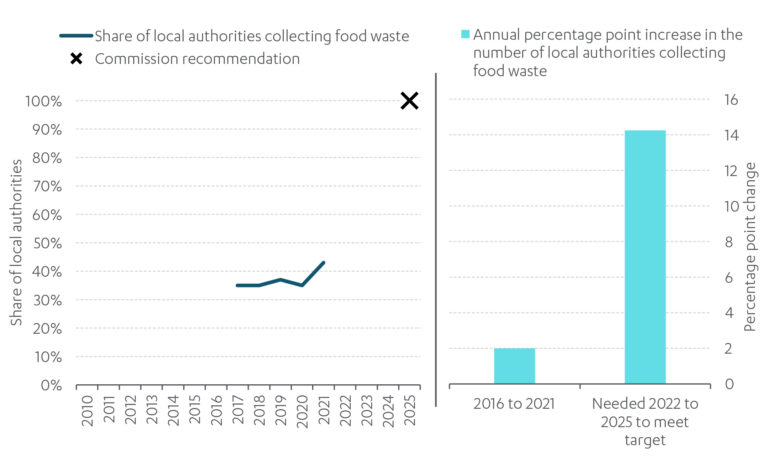

Government must do more to increase waste recycling rates. The Resources and Waste Strategy and the Environment Act 2021 indicated an ambition to incinerate less and recycle more. In line with the Commission’s recommendations, government set targets to recycle 65 per cent of local authority collected waste by 2035, 62 per cent of plastic packaging by 2030, and achieve universal food waste collection by 2025. However, despite having clear overall targets, recycling rates have stagnated since the mid 2010s: local authority collected waste recycling rates have plateaued at around 40 per cent, as have plastic packaging recycling rates, and only around 40 per cent of local authorities currently have separate food waste collections. Unless clear rollout plans are now put in place, these recycling targets will be missed, and the sector will remain a major source of carbon emissions.

Getting back on track

To get back on track, government needs to take a more consistent and committed approach to policy and delivery. Government’s infrastructure ambitions are essential. But they are also challenging to deliver.

The Commission recommends that going forward, government should embed four key principles in its approach to infrastructure policy making:

- Develop staying power to achieve long term goals. Continued chopping and changing of infrastructure policy creates uncertainty. This uncertainty creates a cost for business and delays or deters investment. For example, government’s stop start approach to energy efficiency policy has led to low rates of installations over the past decade; and uncertainty associated with the future of the Cambridge-Milton Keynes-Oxford growth arc has likely inhibited growth and deterred inward investment. In contrast, where government has created policy stability, investment has followed. For example, the contracts for difference mechanism has provided certainty to developers and resulted in rapid deployment of renewable electricity generation. Similarly, government’s stable policy on broadband, alongside network competition, facilitated significant investment leading to gigabit capable coverage increasing from five per cent of premises in 2018 to over 70 per cent of premises in 2022. Government must create greater certainty around key projects, such as High Speed 2, to follow through on its long term goals.

- Fewer, but bigger and better interventions from central government. Meeting the challenges of net zero requires clear strategic focus. The need for rapid progress to tackle climate change is becoming ever more apparent; the risk of delay is now bigger than the risk of building more infrastructure than is needed. But government continues to expend too much effort on many small scale funding interventions and repeated consultations, trying to maintain optionality in all areas. This leaves key strategic policies — such as business models for hydrogen and carbon capture and storage, taking a decision on the role of hydrogen for heating, and putting policy in place for getting off gas — unfinished. Going forward, government will need to take some strategic bets; such as the recent commitment to £20 billion funding to support key new energy technologies.18 Making small steps forward in all directions will not bring about the scale of change in infrastructure needed to meet the Sixth Carbon Budget and deliver a net zero economy. Government must now focus on the small number of areas where it can have a big impact and make bold decisions.

- Devolve funding and decision making to local areas. Long term planning and funding decisions taken at the right spatial level will better reflect local economic and social priorities and avoid distorted incentives created by pursuing myriad national grants. Evidence suggests that with good quality institutions and limited fragmentation across economic areas, devolution is positively associated with productivity and growth.19 Moreover, devolving decision making allows central government to stay more focused on key national priorities. Government has committed to extending and simplifying devolution across the country and giving local leaders greater control over how funding is spent. Where progress has been made, for example with the extension of Metro Mayors, positive impacts are being seen. The trailblazer deals and single multi year budgets announced for Greater Manchester and West Midland Combined Authorities are exemplars. Government must complete the move away from competitive bidding processes and implement flexible, long term devolved budgets for all local transport authorities. The missing link is fiscal devolution and allowing greater revenue raising powers at a local level. Local leaders should be able to fund as well as find their own local infrastructure solutions. This would create stronger economic incentives to drive local economic growth and provide resources for city regions and Mayoral Combined Authorities to contribute to the costs of improving local infrastructure. The Commission is looking at the scope for transport user charges to support local transport infrastructure – and this principle could be applied to areas such as business rates growth retention.

- Remove barriers to delivery on the ground. The planning system for handling nationally significant infrastructure projects has slowed in recent years, with the timespan for granting Development Consent Orders increasing by 65 per cent between 2012 and 2021.20 Not only does this mean that much needed infrastructure is not getting delivered, but it also adds significant cost which will ultimately be paid for by consumers and taxpayers. The system needs to return to the situation in 2010 where projects were typically taking two and a half years to achieve consent.21 Recent publication of the draft National Networks National Policy Statement is a step in the right direction. Government must now publish the final National Policy Statement for Energy. Decarbonising the electricity system will require over 17 transmission projects to receive development consents in the next four years, a fivefold increase on current rates.22 The Commission will publish its study on the infrastructure planning system shortly and the Commission hopes government will rapidly progress its recommendations.

Alongside these four key principles to embed in policy making, the Commission is calling on government to progress ten actions over the next year (figure 3). These actions will help get government back on track to delivering the Commission’s recommendations and tackling the challenges of net zero, regional growth, and climate resilience.

Figure 3: Government actions for the year ahead

| Theme | Targeted action for the year ahead |

|---|---|

| Supporting growth across regions | Move away from competitive bidding processes to give local areas more flexibility and accountability over economic growth funds, and implement flexible, long term devolved budgets for all local transport authorities |

| Demonstrate staying power by progressing the Integrated Rail Plan for High Speed 2 and Northern Powerhouse Rail and remaining committed to the £96 billion investment required | |

| Follow through on commitments made in 2018 to the Cambridge-Milton Keynes-Oxford growth arc, by setting out how the road and rail infrastructure to support new houses and businesses will be delivered | |

| Net zero and energy security | Deliver a significant increase in the pace of energy efficiency improvements in homes before 2025, including tightening minimum standards in private rented sector homes, to support delivery of the government’s target for a 15 per cent reduction in energy demand by 2030 |

| Remove clear barriers to deployment in the planning system by publishing National Policy Statements on energy to accelerate the consenting process for Nationally Significant Infrastructure Projects | |

| Accelerate deployment of electric vehicle public charge points to reach the government’s expectation of 300,000 by 2030 and keep pace with sales of electric vehicles | |

| Ensure that Ofgem has a duty to promote the delivery of the 2050 net zero greenhouse gas emissions target | |

| Building resilience and enhancing nature | Implement schedule 3 of the Flood and Water Management Act 2010 this year and without delay |

| Rapidly put in place plans to get on track to reduce per person water consumption to 110 litres per day by 2050, starting by finalising proposals on water efficiency labelling and water efficient buildings this year | |

| Initiate a step change in recycling rates, including for food waste, by proceeding with the Consistency of Recycling Proposals, and finalsing the Extended Producer Responsibility and Deposit Return Scheme |

The Next National Infrastructure Assessment

Later this year the Commission will publish the second National Infrastructure Assessment. This will set out a series of further recommendations for government to meet the challenges of delivering growth across regions, meeting net zero, and enhancing climate resilience and the environment.

Next Section: Approach to reviewing progress

The government established the National Infrastructure Commission to assess the UK’s long term infrastructure needs, provide impartial, expert advice on how to meet them, and hold the government to account for delivery. The Infrastructure Progress Review is the Commission’s annual monitoring report and sets out the Commission’s views on the extent to which the recommendations government has endorsed have been progressed and delivered over the past 12 months.

Approach to reviewing progress

The government established the National Infrastructure Commission to assess the UK’s long term infrastructure needs, provide impartial, expert advice on how to meet them, and hold the government to account for delivery. The Infrastructure Progress Review is the Commission’s annual monitoring report and sets out the Commission’s views on the extent to which the recommendations government has endorsed have been progressed and delivered over the past 12 months.

The 2023 Infrastructure Progress Review reviews the government’s progress over the past year against the recommendations from the 2018 National Infrastructure Assessment and the studies the Commission has published and which the government has responded to. The Commission uses five tests to assess progress in delivering endorsed recommendations. Each test is assessed to be either met, partially met, or not met. The judgements the Commission has made are supported by evidence, which is summarized in this document. The Infrastructure Progress Review is focused on assessing government progress against meeting those of its recommendations which government has endorsed, or where government has set out alternative proposals to the Commission’s recommendations. It does not give an overall view on government’s progress on infrastructure policy and delivery more widely.

The government’s existing commitments

To date, the government has responded to the Commission’s National Infrastructure Assessment, and eleven studies, most recently The Rail Needs Assessment, Engineered greenhouse gas removals, and Infrastructure, Towns and Regeneration.

The Commission expects government to respond to its latest study Reducing the risk of surface water flooding in 2023. The Commission will make new recommendations to government in the upcoming second National Infrastructure Assessment, which will be published in 2023.

The five tests

The Commission uses five tests, described below, to assess government’s progress in delivering endorsed recommendations over the past year:

- Taking a long term perspective: government should look beyond the immediate spending review period and sets out its plans over the next ten to 30 years

- Clear goals and plans to achieve them: there should be a specific plan for government policy ambition or endorsed Commission recommendations that is commensurate with the task and contains clear deadlines and identified owners

- A firm funding commitment: where necessary policy ambition should be supported by firm funding commitments commensurate with the level of investment needed to deliver the required infrastructure

- A genuine commitment to change: the Commission has recommended that, in some areas, fundamental shifts in policy are required; government policy should respond in the same spirit

- Delivery on the ground: looking beyond policy, infrastructure should be changing in line with the Commission’s recommendations, providing better services to consumers and taxpayers now.

The Commission ranks progress against the five tests into three categories: not met, partially met, and met:

- Not met: no or limited action has been taken by government to meet the test, and government is not on track to meet the test over the coming years. Substantial and sustained action is required to get on course to meet the Commission’s recommendation.

- Partially met: material action has been taken that will bring about a real change, but not one that is fully commensurate with the test being met; to meet the Commission’s recommendation more action will be needed.

- Met: current policy fully meets the test and a substantial part of the Commission’s recommendation is on track to be delivered.

Ranking against the test reflect the Commission’s judgements. The judgements are supported by a comprehensive analysis of the evidence, which is summarised in the rest of this report. For policy to be fully on track to implement the Commission’s recommendation, each test should be ranked as met.

Story of progress against the Commission’s recommendations

Next Section: Digital

Government continues to make good progress on supporting deployment of new digital infrastructure networks. Delivery of full fibre and gigabit capable broadband is progressing rapidly. And government has set out ambitious targets for 4G coverage in the Shared Rural Network agreement with industry. Across both fixed and mobile networks, government must ensure that hard to reach areas do not get left behind. In addition, Government must now set out a clear vision for 5G mobile networks in the upcoming Wireless Infrastructure Strategy.

Digital

Government continues to make good progress on supporting deployment of new digital infrastructure networks. Delivery of full fibre and gigabit capable broadband is progressing rapidly. And government has set out ambitious targets for 4G coverage in the Shared Rural Network agreement with industry. Across both fixed and mobile networks, government must ensure that hard to reach areas do not get left behind. In addition, Government must now set out a clear vision for 5G mobile networks in the upcoming Wireless Infrastructure Strategy.

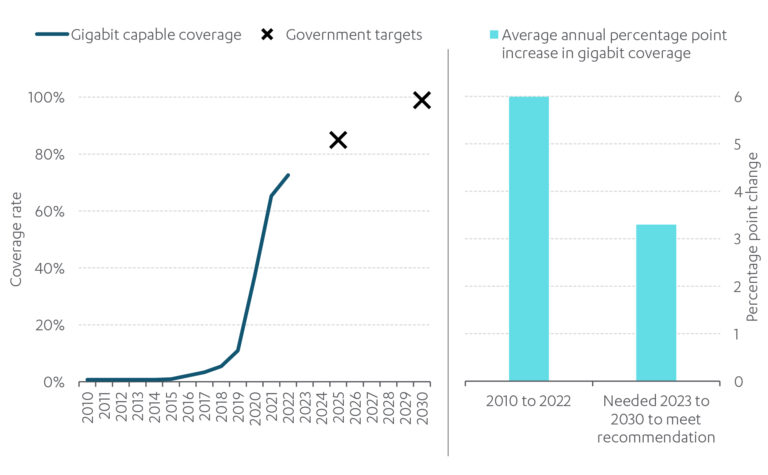

Government has made a genuine commitment to change digital connectivity across the country. Delivery of gigabit capable broadband networks is progressing rapidly and, in 2022, gigabit capable coverage was extended to over 70 per cent of premises. This reflects significant increased investment from operators in recent years. If operators deliver on their published plans, and government maintains the £5 billion subsidy programme for underserved areas, government will achieve its target to deliver nationwide coverage by 2030.

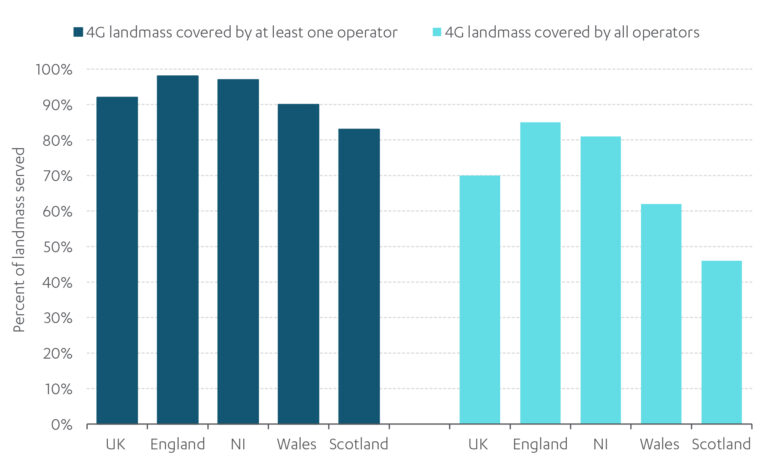

On mobile, 4G coverage from at least one operator now extends to around 92 per cent of the UK landmass, and the Shared Rural Network agreement should increase this to 95 per cent by the end of 2025, with further coverage improvements in the harder to reach areas continuing to be delivered until the start of 2027.

Mobile network operators are also extending their 5G network across the UK, and coverage outside of premises from at least one operator now stands at around 70 per cent. There has also been some improvement on coverage on the road network. However, challenges remain on upgrading mobile coverage on the rail network and securing investment for deploying new 5G networks.

Government must now set out a clear vision for 5G mobile networks in the upcoming Wireless Infrastructure Strategy. The long term commercial and strategic value of 5G will be determined by whether it becomes more than just a faster version of 4G, and whether it provides solutions to pressing problems.

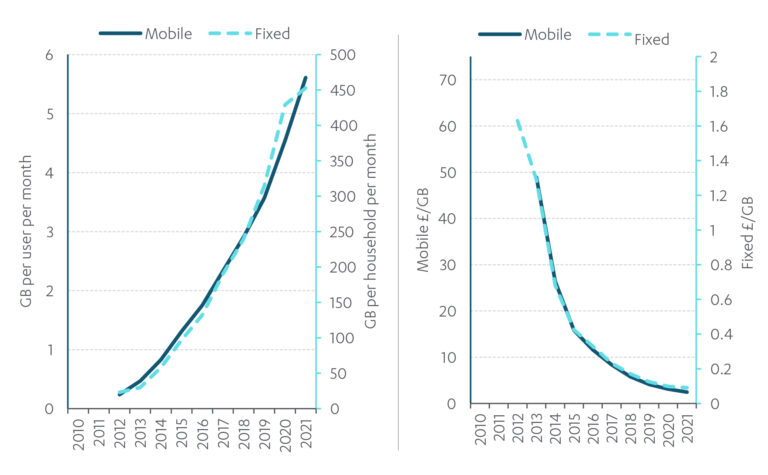

The digital sector

Digital infrastructure covered by the Commission focuses on services accessed by consumers and businesses in two categories: fixed broadband and mobile connections. The digital sector continues to perform well. Increases in consumption have been matched by reductions in unit prices (figure 4). This means consumers now pay less for both fixed and mobile services than they did a decade ago, although April will see above inflation price rises for many broadband and mobile services.23 The UK’s digital infrastructure has demonstrated good resilience. However, in 2022, the number of outages or disruptions increased to 1,280, up from 760 the year before.24 This was, in part, driven by winter storms causing outages on the power network.25

The Commission has set out a more detailed overview of the digital sector in the Second National Infrastructure Assessment: Baseline Report Annex A: Digital and the Commission’s data on sector performance is available online.

Figure 4: Consumption has grown rapidly over the past decade, but unit prices have fallen at the same time

Data consumption and unit price of data, 2012 to 2021, United Kingdom

Source: Ofcom – Communications Market Report (2022)

Progress against the Commission’s recommendations

Commission recommendations

In 2018, the Commission recommended that government set out a nationwide full fibre connectivity plan by spring 2019, including proposals for connecting rural and remote communities, to ensure that full fibre connectivity would be available to 15 million homes and businesses by 2025, and to 25 million by 2030, with nationwide coverage by 2033. A significant number of premises will be commercially unviable for providers to deliver full fibre, so the Commission also recommended that rollout of full fibre to these premises should be partly subsidised by government.

To accelerate delivery, the Commission recommended that Ofcom should promote network competition through deregulation where possible, and by allowing access to Openreach infrastructure for alternative providers. The Commission also argued that government should improve processes to obtain wayleaves for telecommunications providers, promote the appointment of digital champions by local authorities, and work with Ofcom to allow for copper switch off by 2025.

In its Infrastructure, Towns and Regeneration study the Commission also highlighted that many commercially unviable properties will likely be in towns. Analysis suggests that around 20 per cent of towns may be reliant on government support to deliver gigabit capable broadband to more than 20 per cent of their premises.

Government policy

Government has endorsed the Commission’s recommendations on full fibre rollout in the Future Telecoms Infrastructure Review (2018) and its Response to the National Infrastructure Assessment.

In the National Infrastructure Strategy, the government set out its goal to deliver a minimum of 85 per cent gigabit capable coverage by 2025. In the Levelling Up White Paper government built on this target and set an aim to deliver gigabit capable coverage to at least 99 per cent of premises by 2030. Gigabit capable coverage refers to connections that can provide download speeds of 1 Gigabit or higher and can either be delivered through a full fibre connection or a hybrid fibre coaxial cable used by Virgin Media O2.26 The Commission will continue to monitor government progress against its gigabit capable targets going forward.

In March 2021, the government announced Project Gigabit, a £5 billion fund to support the rollout of gigabit capable broadband to homes and premises in the hardest to reach 20 per cent of UK premises, equivalent to around six million premises. The 2020 Spending Review allocated £1.2 billion of this funding for the years between 2021 and 2025. The government has set out the first phases of its procurement programme to extend coverage to hard to reach premises.

Alongside Project Gigabit, both government and Ofcom have undertaken significant policy reform to ensure that the investment signals are right to support rapid deployment of gigabit capable networks. Ofcom published the Wholesale Fixed Telecoms Market Review 2021 – 26, which set out a series of decisions designed to support investment in gigabit capable networks, including policies to allow pricing flexibility and promote competition between networks, where viable.

The government has also continued to remove barriers to deploying new gigabit capable networks. The Product Security and Telecommunications Infrastructure Act received Royal Assent in December 2022. This made changes to the Electronic Communications Code to make it easier for operators to reach agreements to access private land to deploy telecoms infrastructure. It also strengthened the rights of operators to upgrade and share existing apparatus to deploy new networks.27

Change in infrastructure

Progress on gigabit broadband coverage has continued over the past year. Gigabit capable coverage has increased from 65 to 73 per cent (figure 5). Much of the rapid increase in gigabit capable coverage over the past five years is due to Virgin Media upgrading its hybrid fibre network to be gigabit capable, which requires less effort than Openreach upgrading its copper network or new network build.28 However, full fibre coverage has also increased rapidly in the last year from 30 per cent to 45 per cent, and so industry is still on track to meet government’s targets.29 However, rural coverage is lagging coverage in urban areas. As of 2022, over 73 per cent of urban premises in England have access to gigabit capable coverage, but only around 33 per cent of rural premises do.30 This trend is similar in Scotland, Wales, and Northern Ireland.31

Industry has also made a series of positive commitments on gigabit capable rollout. Openreach has committed to spend £15 billion to deliver full fibre to 25 million premises across the UK by the end of 2026, including aiming to reach six million hard to reach homes and businesses across the country. As of November 2022, Openreach’s full fibre coverage footprint stood at 8.7 million premises. In 2021 Virgin Media O2 announced that it would upgrade its entire fixed network to full fibre by 2028, and in July 2022 it announced a joint venture to pass seven million premises with a wholesale full fibre network.32 Challenger firms are also expected to invest £17 billion in full fibre networks by 2025, and are expected to cover 11.5 million homes by the end of 2023.33 The third largest network provider, CityFibre, announced in September 2022 that it had deployed full fibre to more than two million homes, 25 per cent of its overall coverage ambition of eight million premises.34

Figure 5: Government is on track to deliver its gigabit capable targets

Historic coverage and government targets 2010 – 2030 (Left chart), Rates of change in coverage 2010 – 2030 (Right chart), United Kingdom

Source: thinkbroadband – UK Superfast and Fibre Coverage

Note: ‘nationwide’ gigabit coverage by 2030 is defined as at least 99 per cent of premises in Levelling Up White Paper.

Assessment of progress

If operators deliver against their published plans, the government is likely to deliver on its high level targets. But some challenges do remain for government in ensuring coverage is universal. Government is taking a long term approach, with funding and market frameworks in place to deliver clear plans, but it is essential that it accounts for how coverage will be extended to hard to reach premises going forward.

- Taking a long term perspective: Met. Government’s goal for 85 per cent gigabit capable coverage by 2025 and 99 per cent coverage by 2030 looks beyond the current funding cycle and account for future proofing the network.

- Clear goals and plans to achieve them: Met. Government is taking the right procurement approach, focused on premises that lack superfast broadband. It is also positive that more premises are becoming commercial for private sector rollout.35 But government must make sure there are no delays, and that rural premises are able to access gigabit capable connections at the same time as urban premises.

- Firm funding commitment: Met. The £5 billion funding for Project Gigabit aligns with the Commission’s own estimates. But it is important that government allocates the remaining funding through future spending reviews, as needed. Market structures and regulation continue to incentivise significant private sector investment in the networks.

- Genuine commitment to change: Met. While government is making good progress, it must ensure that hard to reach premises are not left behind. Alongside spending money from Project Gigabit to support deployment in areas where the commercial case is weak, it must continue to develop approaches to overcome barriers to access that infrastructure providers face, for example through the recent reforms to the Electronic Communications Code.

- Delivery on the ground: Met. Good progress continues to be made in rolling out gigabit capable networks. Government appears on track to deliver its target of 85 per cent coverage by 2025 and 99 per cent coverage by 2030. Project Gigabit should be able to support connections to harder to reach premises. However, as Virgin Media O2 have upgraded their entire network to be gigabit capable, which resulted in a rapid increase in coverage between 2019 and 2021, coverage can now only be expanded through delivering new full fibre connections.

Mobile connections

In Connected Future, the Commission recommended the expansion of 4G coverage to all UK roads and rail and that government must support rollout of 5G across the country.

To support this, in its study Infrastructure, Towns and Regeneration, the Commission recommended that:

- Ofcom should consider crowd sourced data based on real world usage to improve understanding of mobile coverage and produce insights that can help with further optimising mobile coverage

- government should partner with towns to run innovation pilots for new communications technologies, including 5G use cases.

Government policy

In 2020, government secured the Shared Rural Network agreement with mobile network operators to increase 4G coverage across the country and reduce both total and partial not spots. To do this:

- 95 per cent of the UK landmass should have 4G coverage from at least one operator by the end of 2025, with further coverage improvements in the harder to reach areas continuing to be delivered until the start of 2027

- 84 per cent of the UK landmass will have 4G coverage from all four operators

- collectively operators will provide additional coverage to 16,000 kilometers of road and 280,000 premises.

The deal includes over £500 million of public investment, which is matched by over £500 million of private sector investment.

The government is currently developing a new Wireless Infrastructure Strategy, which will set out a strategic framework for the development, deployment, and adoption of 5G and future networks in the UK over the next decade.36

Change in infrastructure over the past year

In 2022 UK 4G landmass coverage from at least one operator was 92 per cent, and 70 per cent for coverage from all operators (figure 6), compared to 92 per cent and 69 per cent respectively in 2021.37 However, significant disparities between the nations persist (figure 6). This is largely driven by the difference in coverage in urban and rural areas: coverage from all operators is near 100 per cent in urban areas, but for rural areas it is around 67 per cent.38

Coverage on the rail network remains poor and reporting on actual consumer experience of mobile coverage on railways is limited.39 Ofcom published measurement data for mobile coverage along the rail network to the outside of train carriage in December 2019. It found that while predicted coverage may be present along the railways, this did not always mean that consumers had good coverage on trains, and that instead mobile coverage on the railways could be ‘patchy and sometimes non existent’.40 Ofcom did not collect data on coverage inside train carriages and has not reported on mobile coverage along the rail network since 2019. However, Network Rail is entering into agreements with some network providers to upgrade its rail telecoms network and to improve coverage along rail routes.41

Coverage is not the same as consumer experience. Coverage statistics are based on predictions provided by mobile operators rather than user data. Consumer and business’s experience of mobile coverage in certain areas may be very different to the reported numbers.

5G coverage continues to grow. Coverage outside premises from at least one operator has increased from around 50 per cent in 2021 to around 70 per cent in 2022.42 There are now over 12,000 5G deployments in place in the UK, almost double the 6,500 reported in 2021.43 5G deployment has been focused on urban areas where deployments provide additional capacity for mobile broadband in areas of high demand, although availability in smaller towns and along busy transport routes has also been increasing.44 However, to date 5G deployment has been non standalone,45 with the first standalone networks only beginning deployment in 2023.46 A standalone 5G network, where the 5G Radio Access Network is connected to a 5G core, can deliver the full functionality of 5G. In contrast, a non standalone network, where the 5G Radio Access Network is connected to a 4G core, is not able to support the full range of 5G capabilities including, for instance, ultra low latency.

Figure 6: There is now good coverage of the UK landmass by at least one operator, but coverage by all operators is lower

Percentage of 4G landmass covered by at least one operator and all operators, 2022, United Kingdom

Source: Ofcom – Communications Market Report (2022)

Assessment of progress

Government continues to make good progress on delivering nationwide mobile coverage. The Shared Rural Network agreement sets out a clear, long term plan for 4G mobile connectivity across the country. However, while there has been some improvement in road coverage, coverage on the rail network remains poor and must be improved. In addition, the UK still lacks a strategic approach to 5G deployment, and the upcoming Wireless Infrastructure Strategy must address this.

- Taking a long term perspective: Met. There is a long term strategy in place for 4G coverage and government recently released a strategy paper on 5G and 6G.

- Clear goals and plans to achieve them: Partly met. There are clear goals for 4G coverage and plans to deliver them through the Shared Rural Network agreement. However, there is currently no plan in place for delivering 5G. As part of the next National Infrastructure Assessment the Commission will consider what economic infrastructure sectors, such as energy or transport, may create 5G demand in future. Work must also continue establishing better reporting metrics for mobile coverage.

- Firm funding commitment: Partly met. There is clear funding in place for the Shared Rural Network agreement from government and the private sector. The investment case for 5G networks, whether for private or public funding, remains unclear due to the significant level of uncertainty around use cases for 5G.

- Genuine commitment to change: Partly met. On 4G coverage there is a clear commitment to change, and positive steps have been taken over the past year. However, this is not yet the case for 5G.

- Delivery on the ground: Partly met. There continues to be some increases in coverage from 4G networks, with additional sites being deployed to deliver the Shared Rural Network. Coverage on mainline rail networks remains poor, and more needs to be done to report on actual consumer experience of connectivity of trains. 5G networks are at an early stage of deployment, with no standalone networks operational yet.

Next Section: Transport

Transport systems are important for connecting people to economic and social activities. However, constraints on transport infrastructure continue to hold back large cities and towns, preventing them from achieving their productivity potential and hindering quality of life. At the same time, transport remains far too carbon intensive. Progress implementing the Commission’s recommendations, from broadening devolution to decarbonising road transport, has been too slow.

Transport

Transport systems are important for connecting people to economic and social activities. However, constraints on transport infrastructure continue to hold back large cities and towns, preventing them from achieving their productivity potential and hindering quality of life. At the same time, transport remains far too carbon intensive. Progress implementing the Commission’s recommendations, from broadening devolution to decarbonising road transport, has been too slow.

Government has made some progress with devolution, taking forward the commitments from the Levelling Up White Paper to transfer new powers, funding, and responsibilities to City Regions. The trailblazer deals and single multi year budgets announced for Greater Manchester and West Midland Combined Authorities are exemplars. However, devolution must stretch across the whole country not just to major city regions. Progress empowering local authorities and helping them build capacity and capability must continue.

Progress on key transport projects connecting major cities is mixed. The Integrated Rail Plan is a long term plan for rail in the North and Midlands to build new high speed lines and upgrade and electrify existing lines. While government’s commitment to East West Rail in the Autumn Budget is welcome, further action on the Cambridge-Milton-Keynes-Oxford arc remains slow. Greater urgency on delivery is needed or the country will miss a significant growth opportunity.

In 2022, government published critical strategies on decarbonising road transport, which reinforce government’s aim to reach near 100 per cent electric car and van sales by 2030. There are, however, only eight years left to achieve this target. A rapid increase in electric vehicle charge point deployment is needed now to achieve this ambition.

Actions for 2023

Move away from competitive bidding processes to give local areas more flexibility and accountability over economic growth funds, and implement flexible, long term devolved budgets for all local transport authorities.

Demonstrate staying power by progressing the Integrated Rail Plan for High Speed 2 and Northern Powerhouse Rail and remaining committed to the £96 billion investment required.

Follow through on commitments made in 2018 to the Cambridge-Milton Keynes-Oxford growth arc, by setting out how the road and rail infrastructure to support new houses and businesses will be delivered.

Accelerate deployment of electric vehicle public charge points to reach the government’s expectation of 300,000 by 2030 and keep pace with sales of electric vehicles.

The transport sector

Transport infrastructure connects people, communities, and businesses, and is essential to economic growth, productivity, and quality of life. It includes the roads and rail used by transport, stations used by passengers to access the network, fueling infrastructure such as electric vehicle charging points, and ports and airports.

Improving transport connectivity is the most significant way that infrastructure can contribute to improving productivity across the country’s regions. Cities must be well connected to each other so that they can trade in goods and services, and freight distribution networks need to operate efficiently. Urban areas need to be able to expand beyond the limits that congestion places on road capacity, requiring mode shift from cars to other forms of travel. And this needs to be done while improving the environment, particularly reducing carbon emissions to meet carbon budget and net zero targets.

The 30 years before the Covid 19 pandemic saw overall transport passenger miles and freight mileage gradually increasing. Modes of transport have followed different patterns, but the overall trend has been a steady long term increase, driven primarily by a rise in journeys by private car. The pandemic changed travel behavior dramatically. Total volume of travel has now reached close to prepandemic levels.47 The extent to which transport patterns will revert to previous trends, or whether changes in behaviour will become permanent, remains unclear but will be critical for future policy. Network capacity is driven by peak demand, whereas the ability to pay for transport systems is dependent on total revenues. A challenging situation could emerge where peak loading returns to pre pandemic levels, even if on fewer days of the week, but overall passenger numbers and revenue per passenger remain down. This would result in revenues struggling to cover the largely fixed costs of the networks.

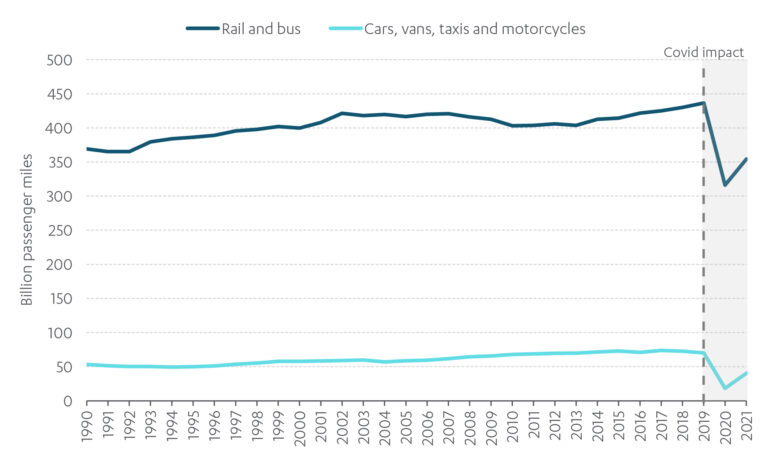

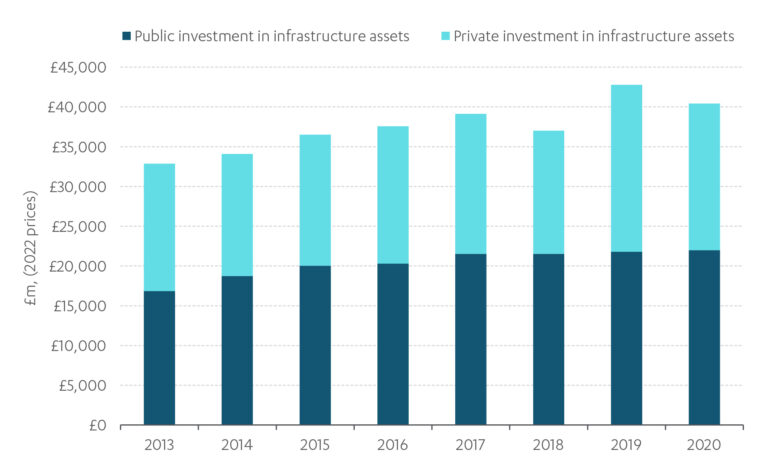

Figure 7: Transport usage has risen over the past 30 years

Annual passenger miles for surface transport, 1990 – 2021, Great Britain

Source: Department for Transport – modal comparisons (2022)

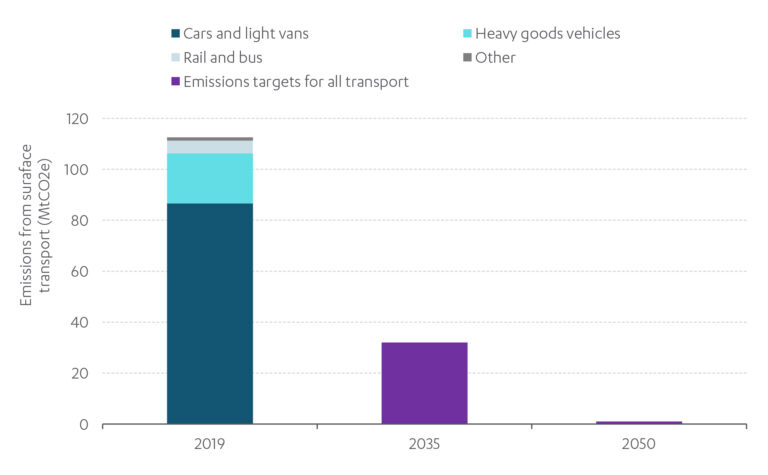

Despite the impacts of the pandemic, transport remains the biggest contributor of greenhouse gases by sector, producing 101 MtCO2e in 2021, or 24 per cent of the UK’s total emissions.48 Emissions from cars and vans accounted for around 75 per cent of the UK’s total domestic transport greenhouse gas emissions in 2019. Emissions from heavy goods vehicles accounted for around 15 per cent.49 Therefore, moving past fossil fuels towards a zero emissions fleet of vehicles is central to reaching net zero.50

Figure 8: Cars and heavy goods vehicles make up the vast majority of surface transport emissions

Historic transport emissions and target for 2035 and 2050, United Kingdom

Source: Department for Transport – Energy and environment (2022), Climate Change Committee Sixth Carbon Budget (2020)

Note: Figure uses 2019 emissions rather than 2020 emissions due to uncertainty around the short term impact the pandemic may have had on emissions.

The Commission has set out a more detailed overview of the transport sector in the Second National Infrastructure Assessment: Baseline Report Annex: F Transport and the Commission’s data on the performance of the sector is available online.

Progress against the Commission’s recommendations

Urban and local transport

Commission recommendations

The first National Infrastructure Assessment recommended that local leaders in city regions outside London be given stable, devolved five year infrastructure budgets.51 The Commission’s study Towns, Infrastructure and Regeneration built on this recommendation, calling for government to provide all county and unitary authorities, or combined authorities where they are in place, with devolved five year budgets for transport and make available expert strategic advice and support for places that lack the capability and capacity to develop their own infrastructure strategies and wider place based plans.52

These recommendations set out how local transport funding should be reformed to enable infrastructure strategies to be developed and led locally, by people who understand the needs and strengths of the area and can take account of the local context. The study highlighted that a permanent transition away from the competitive bidding system that erodes local capacity is needed.

The first Assessment also recommended that government commit long term funding for major urban transport investment. This includes locally raised finance and a process to identify priority cities for transformational upgrade programmes, to be developed in partnership with local authorities.53

Government policy

The Levelling Up White Paper extended devolution beyond metropolitan areas and committed to inviting nine areas to agree new County Deals, with all areas of the country having a chance to agree a deal by 2030. Subsequently, the Spending Review 2021, through the City Region Sustainable Transport Settlements, committed to £5.7 billion for England’s largest Mayoral City Combined Authorities’ for 2022-27, to transform local transport networks through London style integrated settlements. It also committed £5.3 billion funding for local road improvements and maintenance.54 At the Spring Budget 2023 government followed up on this with a further £8.8 billion transport funding for England’s largest Mayoral City Combined Authorities through the City Region Sustainable Transport Settlements from 2027-28 to 2031-32.55

The Levelling Up and Regeneration Bill was introduced into Parliament in May 2022 and expands on devolution by enabling the creation of Combined County Authorities through new devolution deals.56 In 2022, devolution deals were signed for York and North Yorkshire, the East Midlands, Cornwall, Norfolk, Suffolk and the North East.57 At Spring Budget 2023 government promised deeper devolution deals (‘trailblazer deals’) for Greater Manchester and West Midlands Combined Authorities that will give a single multi year funding settlement across local growth policy areas including transport.58

The government issued its response to the Commission’s study Towns, Infrastructure and Regeneration in August 2022. The response recognises the importance of devolution and repeats the commitments from the Levelling Up White Paper to extend the number of areas with devolved powers but indicates that beyond the 5 year settlements already provided through City Region Sustainable Transport Settlements, more bespoke arrangements will be a matter of negotiation in each devolution deal. The response highlights the advisory service the UK Infrastructure Bank is developing to support local authorities to develop infrastructure projects that support net zero or regional and local growth.59

The government has only committed to one large scale urban transport project, announcing as part of the Integrated Rail Plan that it will support West Yorkshire Combined Authority as it plans and builds a mass transit system, at an indicative cost of over £2 billion.60 A statutory consultation has been launched to review the revised West Yorkshire Mass Transit Vision 2040, which sets out the process for developing a new system of transport to make the region greener, more inclusive, and better connected.61

Assessment of progress

Progress with devolution deals in major city regions is welcome, particularly for the Greater Manchester and West Midlands Combined Authorities. However, progress extending devolution beyond these areas is slower. Government’s timeline to finalise devolution deals by 2030 is unambitious and they can and should be delivered much faster. To empower local leaders to deliver regional growth, government must invest sufficient time and resources to deliver new structures:

- Long term: Partly met. The five yearly transport budgets given to England’s largest Mayoral City Combined Authorities’ will enable them to plan ahead. The recent commitment from government of £8.8 billion for the next five years now gives funding certainty for maintenance and enhancements for the next 10 years, a significant step forward. A legislative framework to enable of the cycle of five year city region budgets to be renewed permanently would also help facilitate long term planning. And longer term transformational goals will not be achieved without commitment to planning projects on a larger scale for key cities. Other transport authroties now need to be given the same planning horizon.

- Clear goals and concrete plans to achieve them: Partly met. While positive progress has been made for City Regions, the government’s ambition to establish simplified funding arrangements for places outside cities should be achievable much sooner than 2030. It already has a clear working model for devolved transport budgets, tested in existing Mayoral Combined Authorities through the current City Region Sustainable Transport Settlements, which could be extended.

- Firm funding commitment: Partly met. Funding for England’s largest Mayoral City Combined Authorities is now confirmed for the next five year period (out to 2032). But other places are still waiting to see what scale of investment they should be planning for. The funding made available so far has been sufficient for incremental improvements, but not to enable transformational change.

- Genuine commitment to change: Partly met. There has been some progress with extending devolution, with half the country’s population living in an area with a combined authority or devolution deal in place.62 Additionally, the ‘trailblazer’ deals and single multi year settlements for the Greater Manchester and West Midlands Combined Authorities are a step towards providing local partners with more flexibility and accountability over funding. However there needs to be a permanent shift away from competitive bidding between councils for multiple, centrally controlled, short term funding pot Government accepted the Commission’s recommendation to make expert strategic advice and support available to authorities representing towns, and must continue taking steps to empower local authorities and help them build capacity and capability.

- Delivery on the ground: Partly met. Beyond the West Yorkshire mass transit system, government has not made further plans for major urban transport schemes.

Interurban transport

Commission recommendations

In the Rail Needs Assessment, the Commission set out a menu of rail investment options in the Midlands and the North, including the latter stages of High Speed 2. The Rail Needs Assessment set out five different illustrative packages of rail schemes that could be taken forward, depending on the level of funding made available by government:

- focusing on upgrades with a baseline budget of £86 billion; consistent with rail spending in the North and Midlands proposed in the Commission’s first National Infrastructure Assessment

- prioritising regional links with both a 25 per cent increase (£108 billion) and 50 per cent increase (£129 billion) funding scenario

- prioritising long distance links, again with both a 25 per cent increase (£108 billion) and 50 per cent increase (£129 billion) funding scenario.

The Rail Needs Assessment concluded that focusing on upgrades alone would not meet the strategic objective of levelling up, and that prioritising regional links would likely bring higher economic benefits overall for cities in the North and Midlands than the long distance link packages. The Commission recommended that government should take an adaptive approach to investment and commit to a core set of affordable, stable investments, with a clear funding profile and rigorous costings.

The Commission has also made recommendations on infrastructure to support the Cambridge-Milton Keynes-Oxford arc. The region contains some of the most productive and innovative places in the country, centered around two of the world’s leading universities. There are over two million jobs in the region adding over £110 billion to the economy every year.63 The region is an internationally competitive cluster, with a highly skilled labour force, world leading research facilities, and knowledge intensive firms. The central finding from the Commission’s study Partnering for Prosperity was that rates of house building will need to double if the region is to reach its economic potential, and that this should be delivered through new housing settlements. These housing settlements are being held back by a lack of infrastructure. The Commission recommended that government progress work on East West Rail between Oxford and Cambridge and the Oxford-Cambridge expressway road.

Government policy

The government set out a long term plan for rail in the North and Midlands through the Integrated Rail Plan in 2021, which includes a commitment of £96 billion government investment over the period to 2050. The Integrated Rail Plan committed to:

- the completion of High Speed 2 from Crewe to Manchester

- a new line from the West Midlands to East Midlands Parkway

- a combination of upgrades and new line to connect Liverpool, Manchester and Leeds.

The Integrated Rail Plan also committed to electrifying and/or upgrading three existing main lines, including the Transpennine Route, and set out government’s plans to improve local services and integrate these properly with High Speed 2 and Northern Powerhouse Rail. The adaptive approach recommended by the Commission in the Rail Needs Assessment was taken forward, with a core pipeline of investment and options to potentially roll out further schemes.64 In January 2022, government introduced the High Speed Rail (Crewe – Manchester) Bill to seek the powers needed to construct and operate High Speed 2 between Crewe and Manchester, with an Additional Provision introduced six months later. A further £959 million of funding was made available for the Transpennine route upgrade in July 2022. The government recommitted to core Northern Powerhouse Rail, High Speed 2 to Manchester and East West Rail in the Autumn Statement 2022. In the Spring Budget 2023 government also confirmed that it will make a route announcement for East West Rail in May, along with committing £15 million for local authorities to maximise economic opportunities along the route.

With the annual rate of construction output price growth at 9.7 per cent in 2022, construction inflation is placing pressure on capital budgets.65 The most recent report to Parliament on High Speed 2 indicated that the first phase of High Speed 2 is projected to exceed its target budget.66 The Department for Transport has recently announced that, due to inflationary and affordability pressures, construction on phase 2a between Birmingham and Crewe will be rephased by two years and Euston station will also not be completed until later in the programme.67

In the Cambridge-Milton Keynes-Oxford Arc, government remains committed to the East West rail link. However, plans for the Oxford Cambridge Expressway have been cancelled. Government argued that, despite initial commitments, it was no longer possible to deliver the scheme and its benefits at a reasonable cost.68 To support the region government began creating a spatial framework to help develop a strategic vision for the Cambridge-Milton Keynes-Oxford arc and facilitate the successful deployment of the East West rail link. A draft spatial framework for consultation was due to be published in autumn 2022, with implementation of the final framework shortly after.

Change in infrastructure over the past year

The first phase of High Speed 2 is under construction, with work underway at over 350 active sites. This phase is due for completion in stages between 2029 and 2033, depending on further approval for later stages.69

The East West Rail project will be delivered in three connection stages: Oxford to Bletchley and Milton Keynes, Oxford to Bedford and Oxford to Cambridge. As part of connection stage one, the upgrade of the rail connection between Oxford and Bicester was completed in December 2016. Further work on connection stage one is underway on the line that links Bicester to Bletchley and Milton Keynes. This includes reconstructing and repairing existing sections of the line and sections that are no longer in use. Services between Oxford and Milton Keynes via Bletchley are expected to commence in 2025.70 71

Assessment of progress

The Integrated Rail Plan sets out government’s plan to deliver major long term investments to improve rail for the North and Midlands in the face of public spending constraints. However, progress is less positive on the Cambridge-Milton Keynes-Oxford Arc. Although some progress has been made on East West rail, the Oxford-Cambridge Expressway has been cancelled and there has been no further progress on publishing the spatial framework. The region presents a significant growth opportunity for the UK but this will be missed if long term certainty is not provided..

- Long term: Partly met. The Integrated Rail Plan considers the next 30 years, providing a long term plan for rail in the North and Midlands to build new high speed lines, stations, and upgrade and electrify existing lines. However, the long term vision for the Arc is less clear.

- Clear goals and concrete plans to achieve them: Partly met. The Integrated Rail Plan is a realistic plan, that takes an adaptive approach and includes a set of strategic objectives and a timeline for when they should be achieved. Government must continue to provide certainty that the commitment in the Plan will be delivered. There has been wavering commitment to the Arc in the last year. Government should clarify their vision for the direction of the Cambridge-Milton Keynes-Oxford region, including the expected roles of different stakeholders and the intention for the spatial framework.

- Firm funding commitment: Partly met. Significant funding has been allocated through the Integrated Rail Plan for High Speed 2 and to part of the East West Rail route. The full route for all stages of East West Rail should be announced as soon as possible and long term funding should be forthcoming to enable construction of the remaining parts of the line to start in mid 2020s.

- Genuine commitment to change: Partly met. The Integrated Rail Plan sets out the ambition to significantly improve connectivity into and between major population centres in the North and Midlands. It is the largest public investment in Britain’s rail network. Additionally, it takes an adaptive approach, setting out a core pipeline of investment that should speed up delivery of benefits for communities and businesses. Government should continue to take an adaptive approach to ensure that the project does not overrun in terms of costs and delivery dates.

- Delivery on the ground: Partly met. Some progress is being made on the projects committed in the Integrated Rail Plan and to construct East West Rail. However, the Oxford Cambridge Expressway has been cancelled. Delays to delivery of High Speed 2 will inevitably delay the benefits of greater connectivity that are crucial to the economies of towns and cities across the North and Midlands – government must act to create a greater sense of certainty around the whole project and ensure that there are no delays to the current timetable for High Speed 2 services reaching Manchester.

Deploying electric vehicles

Commission recommendations

Emissions from cars and vans accounted for around 75 per cent of the UK’s total domestic transport greenhouse gas emissions in 2019. The transition of the fleet to electric vehicles will be one of the most important actions to decarbonise the transport sector. In the National Infrastructure Assessment, the Commission recommended that government, Ofgem and local authorities should enable the rollout of charging infrastructure sufficient to allow consumer demand to reach close to 100 per cent electric new car and van sales by 2030. To facilitate this a national network of both rapid and slower chargers will be needed. To support this the Commission recommended that:

- government should subsidise rapid charge points in rural or sparsely populated areas of the country where the market alone is unlikely to deliver; a visible core network of rapid chargers is critical to give drivers confidence and tackle range anxiety

- Ofgem ensure that charge points can contribute to the optimisation of the energy system and work with network operators and charge point providers to identify areas where anticipatory investment in the networks may be needed.