Rail Needs Assessment for the Midlands and the North: Final report

The final report of the Commission's study.

Tagged: Transport

In brief

Rail has the potential to contribute to economic transformation in the Midlands and the North. But to give it the best chance of doing so, rail investment must be concentrated and at scale, and form part of a wider economic strategy including skills, development and urban transport. Government should use an adaptive approach and commit to an affordable, deliverable, fully costed pipeline of core investments to improve rail in the Midlands and the North. If further funding is available there could then be options to either enhance these schemes or add further schemes later.

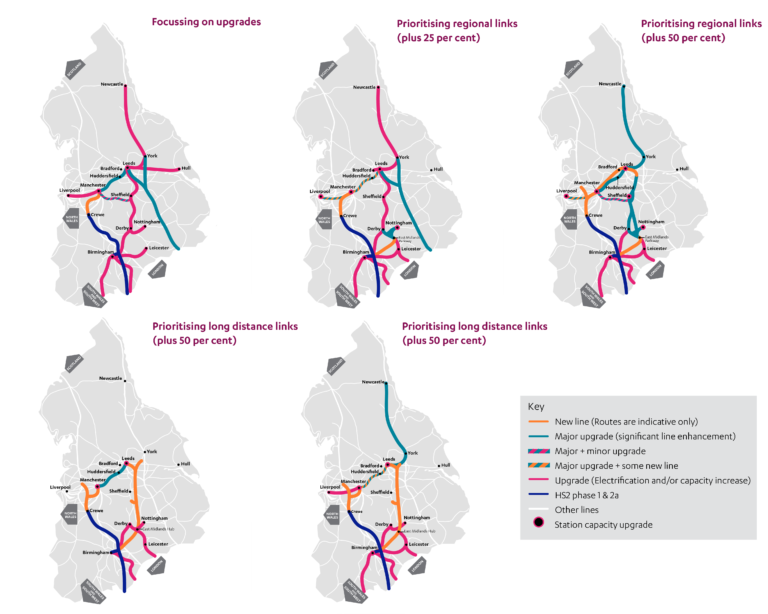

To support government’s decision, the Commission has developed a menu of options for a programme of rail investments in the Midlands and the North, using three different illustrative budget options (baseline, plus 25 per cent and plus 50 per cent):

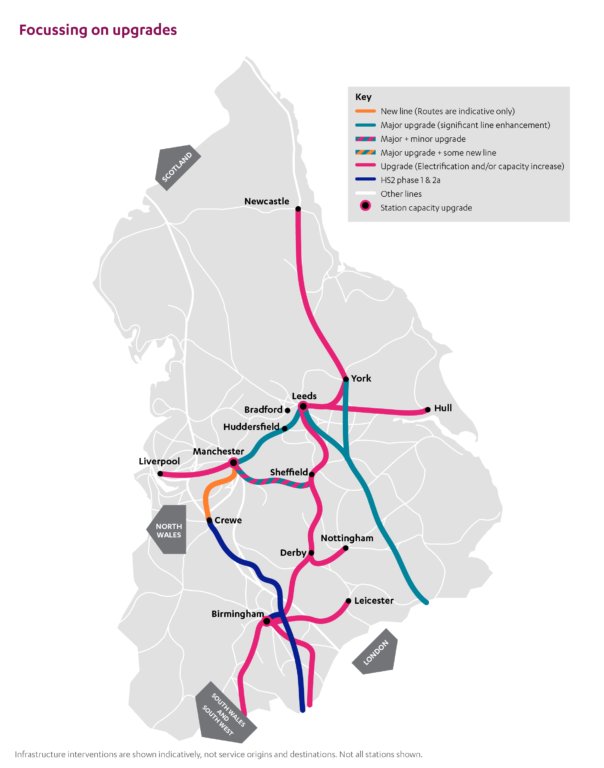

- focussing on upgrades (baseline budget only)

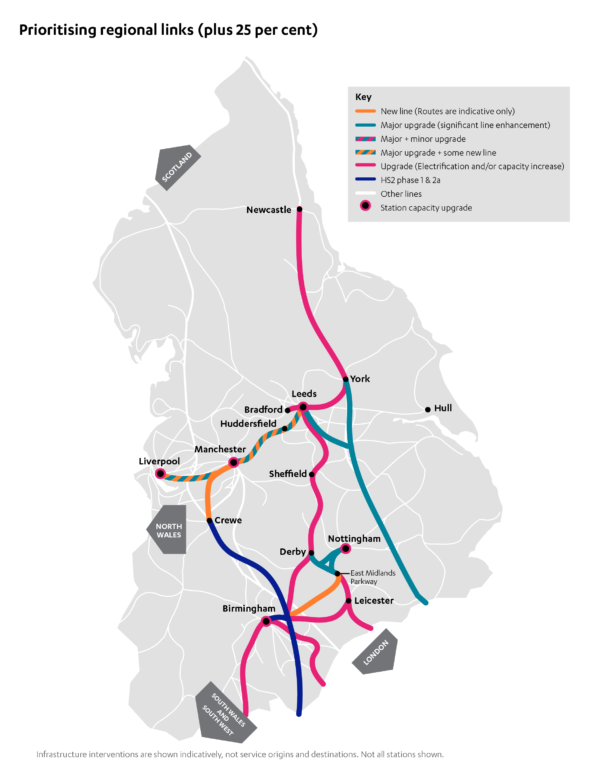

- prioritising regional links

- prioritising long distance links.

The package focussing on upgrades is unlikely to be sufficient to support levelling up. Prioritising regional links appears to have the highest potential economic benefits overall for cities in the Midlands and the North and would improve many of the currently poorest services.

Even in the ‘plus 50 per cent’ budget, there is not enough money for all the proposed major rail schemes in the Midlands and the North, which total up to £185 billion.i While there is an argument for increasing the budget to plus 50 per cent, government would need to balance this against spend on other important aspects of economic infrastructure. The packages in the ‘plus 50 per cent’ budget have higher potential benefits, but higher risks. This level of investment would be a strategic bet.

As part of an adaptive approach, the government could sensibly begin by committing to a core set of programmes. If further funding is available, government could add additional schemes, or enhance existing schemes if:

- the core pipeline is delivering on time and to budget

- the costs and benefits of additional schemes are well developed

- complementary investments are being made that increase the likelihood of major rail investments delivering benefits.

Government should also consider ways of accelerating the benefits of the Plan to deliver benefits faster for passengers in the North and Midlands.

Next Section: Foreword

The forthcoming Integrated Rail Plan takes place against the disrupting impact of the Covid-19 pandemic and a period of economic turbulence. Government will need to make crucial choices about rail investment in a climate of uncertainty. While old patterns of work and mobility may not return, our judgement is that it is unlikely that the current circumstances will put an end to the desire or need to travel within and between our towns and cities over the longer-term.

Foreword

The forthcoming Integrated Rail Plan takes place against the disrupting impact of the Covid-19 pandemic and a period of economic turbulence. Government will need to make crucial choices about rail investment in a climate of uncertainty. While old patterns of work and mobility may not return, our judgement is that it is unlikely that the current circumstances will put an end to the desire or need to travel within and between our towns and cities over the longer-term.

Indeed, at this critical juncture, we must harness every benefit that infrastructure investment can bring. The government’s Integrated Rail Plan represents a golden opportunity to bring clarity, stability and pragmatism to future rail planning. Strategic and long term investment in rail is necessary both to ensure passengers have a service fit for the long term, and as part of a wider economic strategy to rebalance regional growth and maintain national competitiveness.

The Plan also presents an opportunity to avoid the mistakes of the past. It is better to under promise and overdeliver than for rail schemes to be cancelled or cut back because costs have risen. The Integrated Rail Plan should provide a strong commitment to schemes that are sufficiently developed and costed. If more money becomes available, additional schemes or enhancements could be included as part of an adaptive approach.

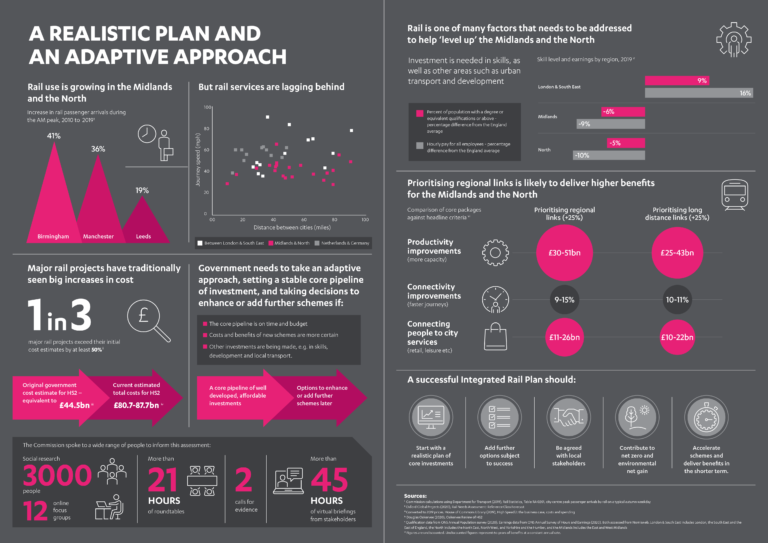

We listened to more than 3,000 people in the Midlands and the North, with more than 21 hours of roundtables and 45 hours of virtual briefings from stakeholders, to inform our report, and while the railway needs to deliver what people care about, not everyone will be able to get the exact scheme they want or to the timescale they’d prefer. The Commission’s assessment of rail needs in the Midlands and the North sets out a range of options to maximise and accelerate benefits for these communities.

The work for this report was undertaken at pace between July and November and has necessarily relied on the evidence that others have produced so is a high level strategic analysis of options. The NIC team have worked enormously hard to pull together and analyse this evidence in quick time and all working at a distance through the pandemic. We are extremely grateful to them all and for the help of the work of secondees from Network Rail, Office of Rail and Road and the Department of Transport.

This report sets out three illustrative budget options and assesses the merits offered by various packages of interventions. Although it is for government to decide on the appropriate level of investment in rail, the evidence suggests that focusing on upgrades alone, the option with the lowest cost, would be insufficient to make real progress towards ‘levelling up’ our economic geography.

Even in the highest budget option we have considered, there is not enough money for every rail scheme proposed. Our analysis suggests that prioritising regional links, for example from Manchester to Liverpool and Leeds or Birmingham to Nottingham and Derby, has the potential to deliver the highest benefits for cities in the Midlands and the North.

While major projects will be vital to enhance connections between cities, where rail can be most effective, it could take many years for the economic impact of a large programme of rail investment to be fully felt. The Commission’s findings should be considered alongside its previous recommendations for further devolution, to give local leaders the powers and funding they need to reshape transport within cities – strategies that could be realised much more quickly.

Our Victorian heritage once made the UK the envy of the world, but today our rail performance lags behind that of many of our European neighbours. Ultimately it will be for government to decide where public resources should be prioritised, but this report offers an evidence-based review of some of the options currently available and the choices that need to be made.

In turn it is our hope that the government’s forthcoming Integrated Rail Plan paves the way for a better-connected, more prosperous Britain, where economic success is shared more evenly across the country.

Sir John Armitt, Chair

Bridget Rosewell, Commissioner

Andy Green, Commissioner

Next Section: Executive summary

The Integrated Rail Plan for the Midlands and the North is an opportunity for government to bring clarity, stability and pragmatism to future rail planning, and avoid the mistakes of the past. Government should commit to a core pipeline of stable, affordable investments, as part of a wider economic strategy for levelling up. The Commission’s analysis shows that prioritising regional links is likely to deliver the highest potential economic benefits to the Midlands and the North.

Executive summary

The Integrated Rail Plan for the Midlands and the North is an opportunity for government to bring clarity, stability and pragmatism to future rail planning, and avoid the mistakes of the past. Government should commit to a core pipeline of stable, affordable investments, as part of a wider economic strategy for levelling up. The Commission’s analysis shows that prioritising regional links is likely to deliver the highest potential economic benefits to the Midlands and the North.

Rail has the potential to contribute to economic transformation in the Midlands and the North. To give rail the best chance of doing so, investment must be concentrated and at scale, and form part of a wider economic strategy including skills, development and urban transport. This includes giving city leaders the powers and funding to develop long term strategies for improving urban transport, which can bring benefits faster than major intercity rail.

To support government’s decision, the Commission has developed a menu of options for a programme of rail investments in the Midlands and the North, using three different illustrative budget options (baseline, plus 25 per cent and plus 50 per cent):

- focussing on upgrades (baseline budget only)

- prioritising regional links

- prioritising long distance links.

The package focussing on upgrades is unlikely to be sufficient to support levelling up. Prioritising regional links appears to have the highest potential economic benefits overall for cities in the Midlands and the North.

Government should commit to an affordable, deliverable, fully costed pipeline of core investments to improve rail in the Midlands and the North. If further funding is available there could then be options to either enhance these schemes or add further schemes later if:

- it is clear the pipeline of core schemes is delivering on time and within the budget

- additional schemes or enhancements are sufficiently developed with robust cost ranges

- complementary investments are being made.

Government must also consider ways to ensure the Plan endures and accelerate the benefits to local communities and passengers in the North and Midlands.

Rail and economic outcomes in the Midlands and the North

Rail in the Midlands and the North needs improvement

The Midlands and the North are home to seven out of ten of England’s largest cities, many of which are not far apart. In recent decades, cities such as Manchester and Leeds have experienced rapid population growth in their city centres, mainly driven by young professionals. Nevertheless, the Midlands and the North lag behind London and the South East in terms of productivity.

Improvements to rail services have long been proposed to support and boost economic growth in the Midlands and the North. The number of people commuting by rail into cities in the Midlands and the North was growing fast before Covid-19. Between 2010 and 2019, passenger arrivals by rail during the morning peak increased 36 per cent in Manchester, 41 per cent in Birmingham and 19 per cent in Leeds. However, capacity has not been able to keep up. Trains are often crowded, with peak morning trains operating over capacity in Manchester, Birmingham and Leeds in particular.

Despite the growth in the number of people commuting into city centres, rail journeys between major cities in the Midlands and the North can be slow, and the service unreliable. Trains between Reading and London run at almost double the speed of trains between Manchester and Leeds, which have an average speed of 48 miles per hour. These problems need to be addressed to enable growth in cities in the Midlands and the North and the surrounding towns.

The Commission’s social research, based on a survey of 3,000 people in the Midlands and the North, showed that participants were doubtful that new lines would or could be delivered.

Rail can also improve economic outcomes

The government has made clear that the current position on regional economic disparities is not acceptable and that it has a strategic objective to level-up prosperity across the UK. The Integrated Rail Plan will need to set out a programme of rail investments that has the best chance of contributing to this strategic objective, within a budget that is affordable.

There is a strategic case for investing more in rail as a necessary part of a wider regional growth strategy. While infrastructure investment alone is not sufficient to change the UK’s economic geography, rail can provide a significant contribution to any package of measures aiming to drive transformative change by improving connectivity between cities. Improving rail in the Midlands and the North will also improve the entire UK rail network.

Rail performs a unique function – it can move large numbers of people in and out of congested city centres, where there isn’t enough space for everyone to use cars and air pollution is a concern. Rail also offers fast journeys between city centres. In dense, successful city centres, lack of rail capacity can be a constraint to further growth. Good rail connections into and between cities tend to be present in comparable groups of cities in other countries.1 And none of England’s economic comparators, with similar geography, have poor rail accessibility between cities.2

The government should focus rail investment on places where it can have the most impact, rather than spreading investment too thinly. Good rail connections can support economic growth by:

- increasing the density of clusters of people and businesses, which in turn increases the productivity of firms and workers and thereby supports growth

- facilitating business between cities, as faster, more frequent rail connections (improved ‘connectivity’) increase options for supply chains and markets for firms in each city, supporting the regions’ local industrial strategies

- making places more attractive to live and work in, by facilitating access to a wider range of places, businesses and services (‘amenities’)

- acting as an anchor for commercial investment, by signalling that an area is worth investing in.

The benefits of rail investment depend on certain assumptions

The benefits of rail, as of all long term investments, are not certain. The government will have to consider the following issues to decide whether investing in rail is a good idea, including:

- that the economy will remain focussed on city regions following the Covid-19 crisis or other shocks

- that other technologies, for example digital communication, do not replace rail

- that complementary policies in the Midlands and the North are delivered and work to raise productivity.

These judgements are all set out in more detail in chapter 2.

A core pipeline and an adaptive approach

Large scale rail investment has high costs, and the benefits for economic transformation are not certain, making it a strategic bet. Rail has the best chance of supporting economic transformation if complementary policies are in place. An adaptive approach can help reduce the risks of such a strategic bet, setting a stable core pipeline of investment but enabling further decisions to be made when costs and benefits are more certain.

The Plan should not overpromise

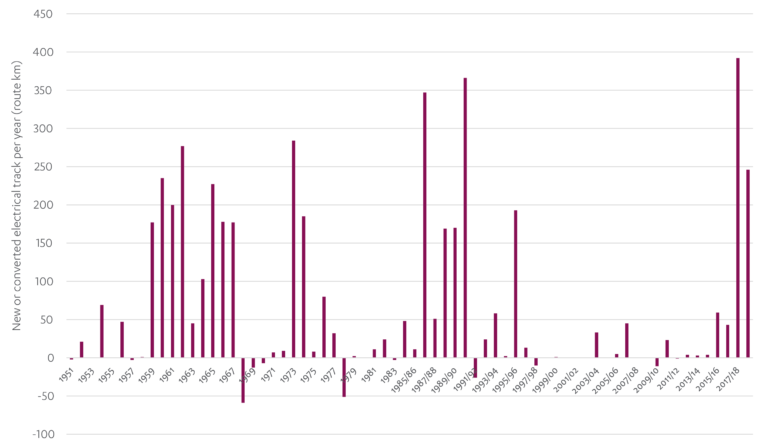

The Integrated Rail Plan presents an opportunity for this government to break the cycle of committing to major rail schemes, underestimating the costs and ultimately having to reopen plans or find additional funding. Rail has a history of overspends. For example, the cost of electrification of the Great Western railway grew by £2.4 billion between 2013 and 2016.3 As set out in the Oakervee Review, the total costs of HS2 were estimated at £80.7-87.7 billion, against a budget equivalent to £62.4 billion.4This suggests that government should begin by focussing on a core set of investments and leaving some decisions on possible enhancements or additional schemes for later.

Making a long term plan and sticking to it are two different challenges. For the rail investments to be delivered to budget and on time, there need to be tight cost controls and rigorous governance. The Infrastructure and Projects Authority should assure and monitor the performance of the Plan at regular intervals to ensure it remains on track.

The Plan should maximise the benefits that rail can deliver

To give the Plan the best chance of supporting growth in the Midlands and the North, it must form part of a wider regional growth strategy, large parts of which should be delivered by and in city regions. To contribute successfully to a wider strategy of tackling regional variability, rail investment should focus on journeys both between cities and into city centres from their surrounding areas. Economic transformation in the Midlands and the North will only occur once the region’s major cities become more productive. But successful cities can also improve the prospects for towns in the vicinity: most successful towns in England are close to successful cities.

Investing in complementary policies such as skills, urban transport, and devolving powers and budgets to locally accountable leaders could both deliver economic benefits to the Midlands and the North in the short to medium term and help maximise the benefits of rail investments in the longer term. The Commission has separately estimated that more than £40 billion is required between now and 2040 to fund major transit schemes in the fastest growing, most congested cities, as well as increased multi-year settlements for transport in all cities.5

An adaptive approach can address these challenges

The Integrated Rail Plan should adopt a long term, adaptive framework for planning. If the government wants to commit to higher levels of investment in rail it should initially set out a firm commitment to a pipeline of affordable core investments, with a clear funding profile and rigorous costings (using the upper end of cost ranges), that should not be reopened.

If further funding is available and can be committed, there could then be options to either enhance these schemes or add further schemes later, subject to certain conditions:

- it is clear the pipeline of core schemes is delivering on time and within the budget

- enhancements and new rail schemes are sufficiently developed with robust cost ranges

- complementary investments, for example in skills, development and urban transport, are being made that increase the likelihood of major rail investments contributing to transformation.

Assessing options for programmes of rail investment

It is for the government to decide how much investment in rail is affordable, given competing demands. While there is a strategic case for investing more in rail, the Commission’s view is that this should not come at the expense of investment in other important and complementary aspects of economic infrastructure, including local urban transport projects.

The Commission has assessed the existing information on the capital costs of different proposed rail schemes and used this to develop potential options for packages of rail investments that fall within three illustrative budgets for rail spending in the Midlands and the North:

- baseline (£86 billion) – a fiscal envelope consistent with the rail spending in the Midlands and the North proposed in the National Infrastructure Assessment’s fiscal remit table (in 2019/20 prices)6

- plus 25 per cent (£108 billion) – a fiscal envelope that assumes the money available for rail spending is 25 per cent higher than in the baseline scenario

- plus 50 per cent (£129 billion) – a fiscal envelope that assumes the money available for rail spending is 50 per cent higher than in the baseline scenario.

The ‘plus 50 per cent’ budget is still not enough to deliver all the proposed schemes in the Midlands and the North. The current total estimated capital cost of HS2, Northern Powerhouse Rail, the Transpennine Route Upgrade, Midlands Engine Rail and other interventions such as decarbonisation and digital signalling is in the region of £140 – 185 billion in 2019-20 prices between 2020 and 2045.7

These budgets include the costs of HS2 Phases 1 and 2a, as these phases are relevant to rail spending in the Midlands and the North. This is also line with the Commission’s fiscal remit which includes the expected cost of projects government has committed to taking forward. However, as Phases 1 and 2a were not in scope of the assessment, their marginal benefits have not been evaluated as part of the Commission’s analysis. Therefore, to provide a fair comparison to the potential benefits of packages, the costs of packages have been provided with Phases 1 and 2a excluded.

Evidence

The volume and complexity of data and the differing approaches across schemes means that completing the analytical programme of work has been challenging. The costs and benefits of many of the schemes in scope have changed during the Assessment, and the costs remain wide ranges. In part, this is because a significant number of schemes are still at a relatively early stage of development – some require refining of complex station or junction proposals, while others are still considering many possible options for routes and stations. The analysis informing this Assessment was finalised prior to the Spending Review and does not take into account any Spending Review announcements.

Government should ensure that costs and benefits continue to be refined as part of the Integrated Rail Plan to better develop the evidence base if it is to avoid past pitfalls. This includes avoiding too early a judgment on realistic costs.

Options for programmes of rail investment

The Commission has developed five packages of rail investment in the Midlands and the North within the three illustrative budget options. The packages are designed to show the choices and trade-offs between strategic objectives. With the limited time available for the study, detailed options of schemes have not been examined in detail. Further planning and design work will be required as part of the Integrated Rail Plan process.

The packages are:

- Focussing on upgrades: by completing the western leg of HS2 Phase 2b and upgrading key existing lines, including the East Coast Main Line and Midland Main Line, in line with the baseline budget (capital costs estimated at £44 billion)8

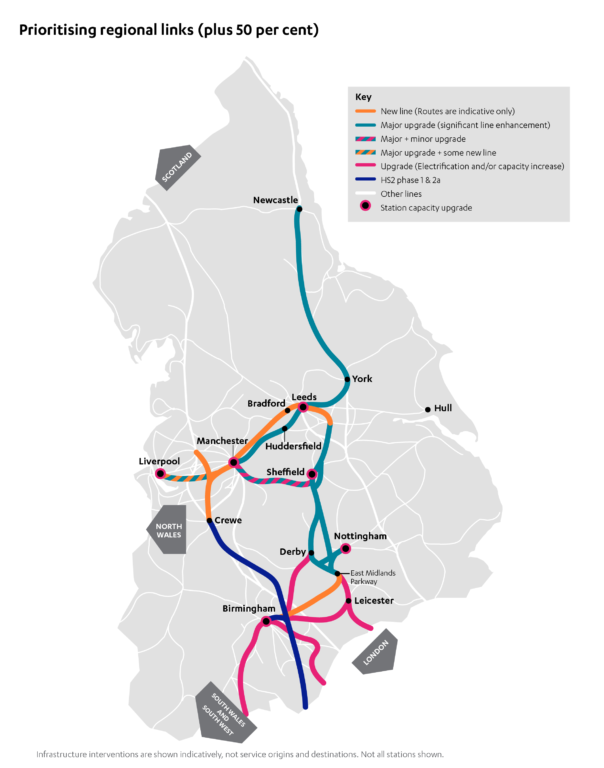

- Prioritising regional links:

- by delivering major upgrades (including some new line) on the Liverpool, Manchester, Leeds corridor, addressing congestion between Leeds and York and improving links to Bradford, a new high speed line from Birmingham to the East Midlands providing direct services to Nottingham, upgrades to the Midland Main Line and East Coast Main Line, improving links to Birmingham Airport and enhancements across the Midlands through the Midlands Rail Hub, in line with the plus 25 per cent budget (capital costs estimated at £69 billion); or

- by building new lines across the Liverpool, Manchester, Leeds corridor which also serve Bradford, increasing capacity between Leeds and Newcastle and upgrading the route from Manchester to Sheffield, delivering a new line into Leeds, providing improved journey times to/from Sheffield, and upgrades to the Erewash Valley route, as well as the Midland Main Line, building a new high speed line from Birmingham to the East Midlands, improving links to Birmingham Airport and enhancements across the Midlands through the Midlands Rail Hub, in line with the plus 50 per cent budget (capital costs estimated at £92 billion)

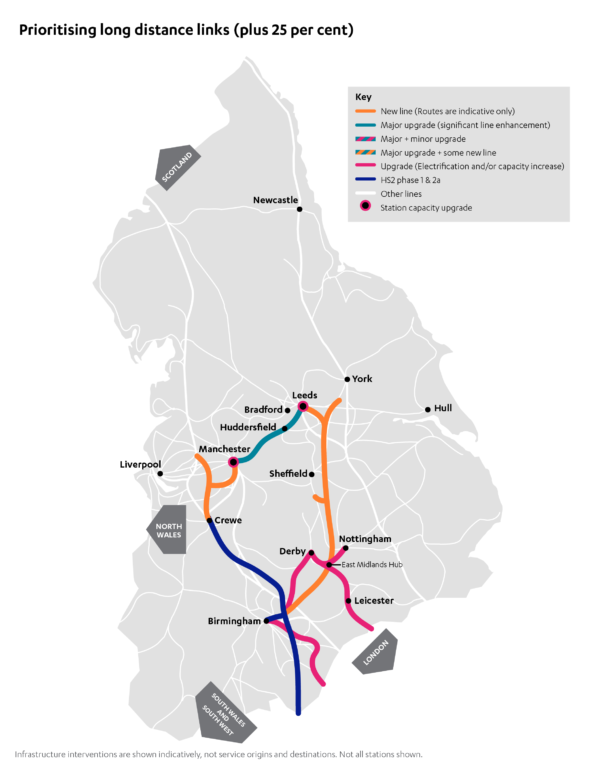

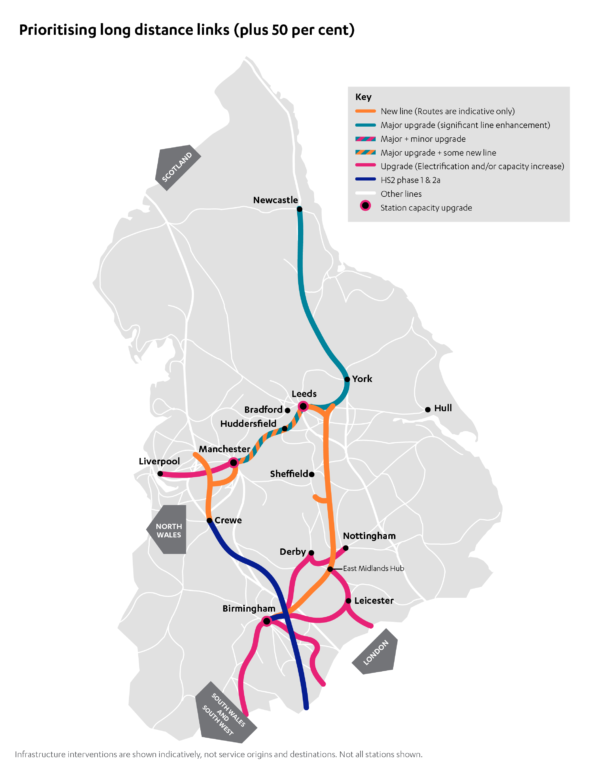

- Prioritising long distance links:

- by focussing on delivering the full HS2 Phase 2b network to improve long distance connections, completing the Transpennine Route Upgrade between Leeds and Manchester, and Midlands Connect schemes that utilise the eastern leg of HS2, in line with the plus 25 per cent budget (capital costs estimated at £68 billion); or

- by delivering the full HS2 Phase 2b network and the other schemes in the ‘plus 25 per cent’ package, as well as adding additional tracks to the Transpennine Route Upgrade between York and Manchester, upgrading connections and capacity from York to Newcastle, and Manchester to Liverpool, and building the Midlands Rail Hub to improve capacity into and across the Midlands, in line with the plus 50 per cent budget (capital costs at £90 billion).

Across each of the packages, the Commission has included at least £15 billion for ongoing transformation programmes for decarbonisation and digital signalling, as well as ‘early wins’, as it is important that these are considered as part of the Plan, and funding for them included (see chapter 6). This could include schemes such as the Northern Powerhouse Rail proposal between Leeds and Hull, or other interventions complementary to planned works, where these have not been covered in a package.

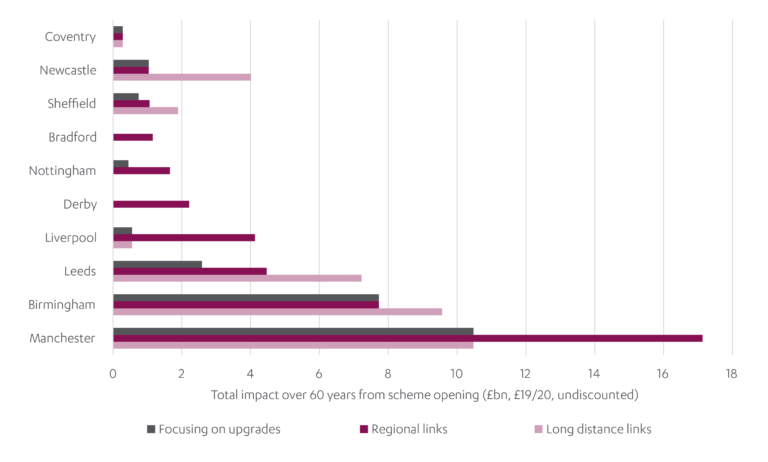

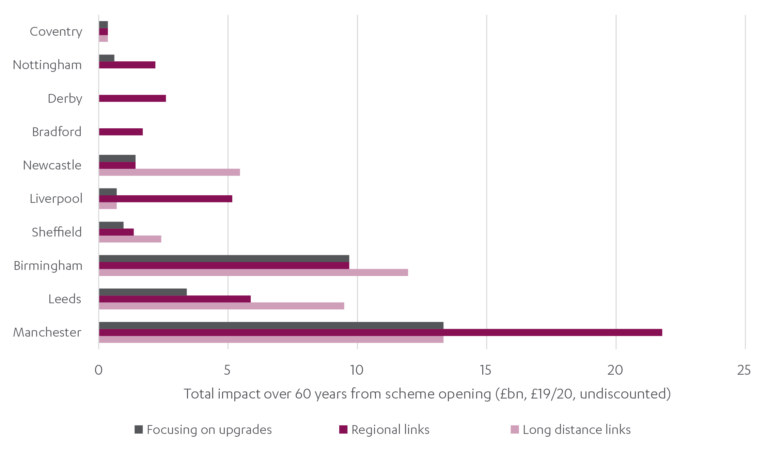

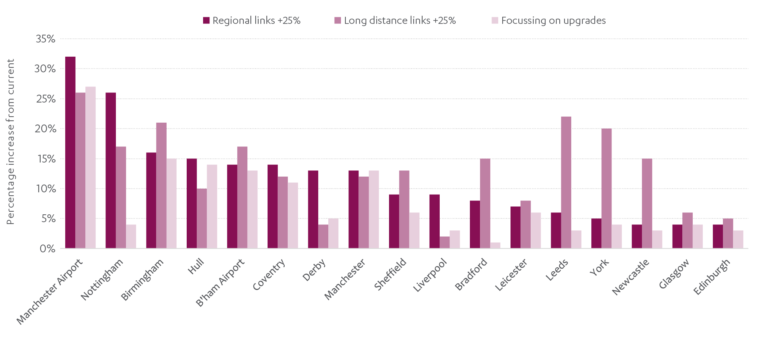

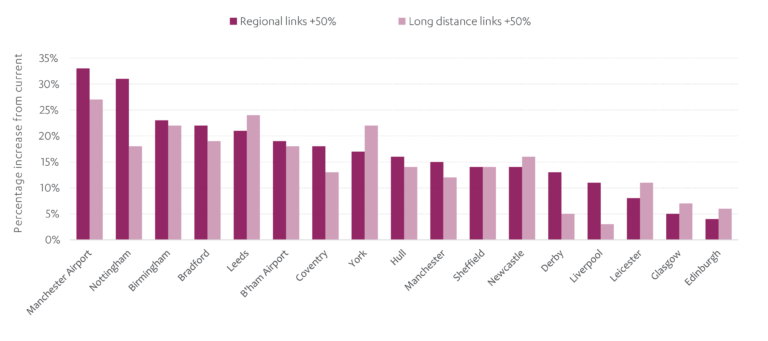

Benefits of packages

The Commission has assessed the benefits of the five packages for economic growth and competitiveness, and for sustainability and quality of life. The Commission used a multi-criteria approach, which was set out in detail in the interim report. Figure 0.1 sets out the headline assessment of the benefits and impacts of the packages that the Commission has quantified, alongside a central estimate for costs (see chapter 4).9 The government’s budget for the Integrated Rail Plan will need to reflect the range of potential costs.

Figure 0.1: Headline benefits and impacts across packages10

| Package | Economic growth and competitiveness | Sustainability and quality of life | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Improvements to connectivity from faster journeys | Improvements to productivity in city centres, undiscounted | Benefits from connecting people to city services, undiscounted | Environmental impact (combined quantified partial valuation of the loss of natural capital and monetised lifecycle carbon impact) | |

| Focus on upgrades | 7% - 9% | £18-30bn | £7-15bn | -£0.3 to -£0.2bn |

| Plus 25 per cent | | | | |

| Regional links | 9%-15% | £30-51bn | £11-26bn | -£0.7 to -£0.5bn |

| Long distance links | 10%-11% | £25-43bn | £10-22bn | -£0.7 to -£0.5bn |

| Plus 50 per cent | | | | |

| Regional links | 11%-19% | £41-71bn | £16-38bn | -£1bn to -£0.8bn |

| Long distance links | 11%-12% | £33-58bn | £13-31bn | -£1bn to -£0.7bn |

As shown in figure 0.1, the packages prioritising regional links are likely to provide the highest combined benefits. At the ‘plus 25 per cent’ budget, the package prioritising regional links has the highest potential improvements for productivity overall in cities in the Midlands and the North, and may also provide higher trade benefits to businesses from faster and more frequent connections between cities (10-15 per cent compared to 10-11 per cent for the ‘plus 25 per cent’ package prioritising long distance links). At the ‘plus 50 per cent’ budget, the package prioritising regional links has the highest potential benefits of all the packages, both in terms of productivity and trade benefits.

The Commission has also considered the potential benefits of the packages for unlocking investment in land around stations, and the potential impact on freight. These are set out in Annexes A-C.

The Commission has also looked at the impact of each of the packages on:

- connectivity with Scotland

- connectivity with the rest of the world (via airports)

- disruption.

All these are covered in more detail in chapter 5.

In this Assessment, the Commission has considered how best to deliver the government’s commitment to improve rail connectivity in the North and Midlands, rather than whether to do it at all. The Commission’s methodology therefore assesses which rail interventions deliver the most potential benefits within a given budget, rather than producing a traditional Benefit Cost Ratio. The numbers in figure 0.1 would only form one part of a traditional Benefit Cost Ratio and should therefore not be interpreted as such. However, with some assumptions, the Commission’s analysis suggests the benefits meet or outweigh the costs of the packages.11 The value for money case is covered in more detail in the modelling annex, published alongside this report. Critically, the Commission’s methodology is intended to guide judgements on which rail investments are most likely to deliver economic transformation as part of a wider strategy – it is the cumulative effects of such a strategy, not the direct impact of rail investment alone, that can deliver significant benefits to the Midlands and the North.

Comparison of packages

The significant increase in the cost of many rail schemes since the National Infrastructure Assessment was published two years ago means that the level of funding set out in that Assessment only provides enough funding for upgrades and some new lines, as demonstrated in the package focussing on upgrades. The package focussing on upgrades is unlikely to meet the strategic objective of levelling up in the North and the Midlands.

Although the option focussing on upgrades provides some improvement to the speed and frequency of trains between cities and capacity into city centres, and has the lowest environmental impact, the benefits it delivers are not at scale and would be less likely to trigger long term economic transformation than other packages.

The packages prioritising regional links are more likely to bring higher benefits, overall, to cities in the Midlands and the North and to support the strategic objective of levelling up, because they:

- improve the quality of regional, largely east to west rail links between cities within the Midlands and the North, which are generally inferior to longer distance rail links

- focus on schemes that can provide the biggest potential improvements in productivity across the Midlands and the North

- deliver greater improvements to connectivity for several key cities, including Nottingham, Coventry, Derby, Manchester and Liverpool, while also providing significant improvements to a range of smaller places, such as Crewe, Doncaster, Huddersfield and Warrington, and potentially Hull under the electrification programme.

- address the biggest problems of existing poor capacity and connectivity, with significant further capacity added to Birmingham, Manchester and around Leeds, particularly on the route to York, and improved connectivity between and within the West and East Midlands, for example improving journey times between Birmingham and Nottingham

- focus improvement on the journeys that people are most likely to take – into cities from the surrounding area, rather than into London (for example, in 2018-19, 60 per cent of rail journeys in Yorkshire and the Humber were between places in the region, while only 10 per cent were to London).

As part of an adaptive approach, the government could sensibly begin by committing to a core set of programmes. Some elements of the major rail projects proposed for the Midlands and the North, including the Transpennine Route Upgrade, Midland Main Line electrification and some Midlands Engine Rail schemes, present opportunities for earlier delivery as work is underway already, or because they are independent of other major schemes.

There is a strategic case for increasing the budget to ‘plus 50 per cent’. However, this high level of investment would be a strategic bet and comes with higher risks. The costs and benefits of all the necessary schemes are not sufficiently well articulated for the Commission to take a firm view on this. If more funding were available, there are options to either enhance these schemes or add further schemes later, under an adaptive approach as set out above.

The Commission has had to develop packages on the basis of existing proposals, which do not necessarily fit within the Commission’s preferred adaptive approach, so it is not possible to set out exactly which additional schemes should be considered under an adaptive framework. However, if the pipeline of investments was based on the Commission’s ‘plus 25 per cent’ package prioritising regional links or something similar, further schemes or enhancements under a ‘plus 50 per cent’ budget could include:

- a phased approach to the remaining sections of the eastern leg of HS2 Phase 2b from the East Midlands to Leeds

- prioritising improved connectivity between Sheffield and Leeds – as set out in the ‘plus 50 per cent’ package prioritising regional links

- improved connectivity between Sheffield and Manchester

- a new line from Manchester to Leeds via Bradford, building on the partial new line option in the ‘plus 25 per cent’ package.12

While the Commission’s analysis suggests that the highest local economic benefits are likely to be delivered by initially prioritising regional links, this does not rule out the further development of options such as the HS2 Phase 2b eastern leg that also have strategic value. There is the possibility of approaching the eastern leg in phases to deliver benefits earlier, starting with a high speed line between the West and East Midlands to significantly enhance capacity and connectivity between these two areas. These schemes should continue to be developed so decisions can be made on the best possible evidence.

It is important that whichever schemes are included in the Integrated Rail Plan, the Commission’s design principles are used to ensure that schemes including stations are well designed and contribute to climate, people, places and value.

Areas of further work

Given the short timeframe for the Assessment, the Commission has had to focus on the strategic case for investment. The Commission has not undertaken the type of detailed railway planning that a project of this scale will need. Government, along with Network Rail and regional transport bodies, will need to ensure that this detailed work is undertaken for the Plan to be a success, both to ensure schemes are sufficiently developed and plan for their effective delivery. In particular, government will need to ensure it has properly considered and planned for the integration of different schemes, both with one another and with the existing rail network.

Further work will also be needed to ensure that the Plan is able to also deliver on long term priorities, such as decarbonisation, and to maximise opportunities for development and regeneration. The latter will be particularly important if government chooses to make changes to the current investment plans. Even the core set of schemes will require further work and refinement as they go through the consents process, but it is important that this is given sufficient focus. More detail on the areas where additional work required is set out in chapter 4.

Long term commitments and shorter term wins

Whichever package of rail schemes the government chooses in the Integrated Rail Plan, the benefits from many of the schemes will likely not be seen until the 2030s or 2040s on current plans. Government should systematically look at how to accelerate the delivery of these schemes, and ensure the Plan delivers benefits in the short to medium term. Steps should be taken to reduce the risk of the core interventions in the Plan needing to be reopened or replaced in future.

Ensuring the Plan endures

Long term transport plans have sometimes been subject to delay due to disagreement and appeals. There are steps government can take to ensure the plan endures:

- Agreeing the Plan with local stakeholders will ensure it reflects local priorities and reduce the risk of the Plan being disputed. Government may also wish to consider strengthening regional transport bodies, and their remits, to ensure that they can most effectively work alongside government and Network Rail to enable a coordinated and prioritised approach to rail investment.

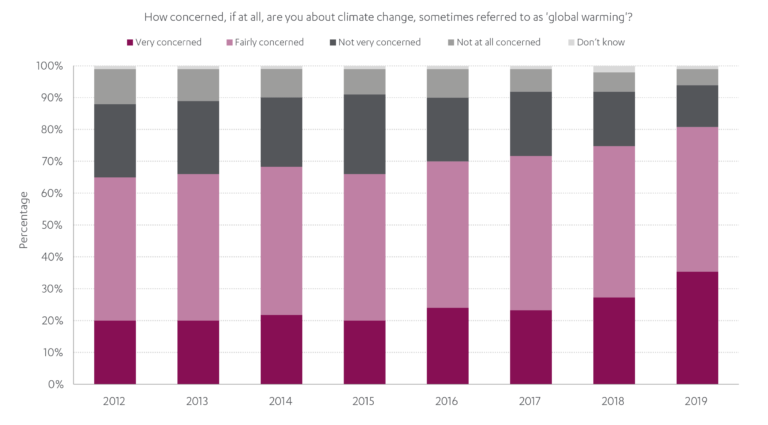

- Ensuring plans contribute to net zero and net environmental gain is important for its own sake but will also avoid the risks of plans being delayed at a later stage due to controversy around the potential environment impact. Decisions on the Integrated Rail Plan should be consistent with the government’s legislative commitment to reaching net zero and transport decarbonisation plans and the Integrated Rail Plan should set out a strategic approach to minimising, and where necessary mitigating, impacts on the local environment and natural capital, adopting a ‘net gain’ approach.

Accelerating schemes and delivering benefits in the shorter term

As set out above, some elements of the major rail projects proposed for the Midlands and the North present opportunities for earlier delivery as work is underway already, or because they are independent of other major schemes. There are also some other schemes, including upgrades on the East and West Coast Main Lines, that need to be progressed earlier in the timeframe to allow other schemes to advance. Government should also ensure necessary upgrades to the conventional network are completed in time to enable the integration of new, faster rail lines like the HS2 Phase 2b western leg.

The Commission has also identified several potential ‘early wins’ that could help deliver benefits for passengers in the North and Midlands within the next decade. These include smaller scale interventions including station improvements to improve passenger experience and enable longer trains and increase capacity, and digital signalling to increase reliability and capacity across the network.

The government is undertaking a programme of work to speed up the delivery of major infrastructure projects. The lessons learnt should be applied to the schemes in the Integrated Rail Plan. From the Commission’s perspective there are several non-infrastructure issues that government should address to help accelerate delivery of major new rail schemes and upgrades, and which would also limit further escalation of rail costs. These include:

- the process for acquiring the necessary consents

- the existing regulatory framework

- certainty for the supply chain

- the approach to upgrading existing lines.

Next Section: Facts & Figures

This infographic from the Rail Needs Assessment shows the key findings from the Commission's research.

Facts & Figures

This infographic from the Rail Needs Assessment shows the key findings from the Commission's research.

Next Section: Background

The government asked the Commission to carry out an assessment of rail needs in the Midlands and the North of England, to inform the development of the government’s Integrated Rail Plan.

Background

The government asked the Commission to carry out an assessment of rail needs in the Midlands and the North of England, to inform the development of the government’s Integrated Rail Plan.

In July, the Commission published an interim report, which covered rail and economic outcomes, the Commission’s methodology, and set out a series of questions for stakeholders.

The Commission conducted an extensive stakeholder engagement process as part of this Assessment, including social research, a call for evidence and several virtual briefings.

Background to the Assessment

Following the Oakervee review of HS2 in February 2020, the government announced its intention to draw up an Integrated Rail Plan for the North and the Midlands which will identify the most effective scoping, phasing and sequencing of relevant investments and how to integrate HS2, Northern Powerhouse Rail, Midlands Rail Hub and other proposed rail investments. This plan will be informed by the Commission’s independent assessment of the rail needs of the Midlands and the North.

The Infrastructure and Projects Authority is conducting a review of the lessons learned from HS2 Phases 1 and 2a on the supply chain and costs for the delivery of the rest of the project, which will also feed into the government’s Plan.

The Commission has previously recommended investing in better rail in the North, particularly in High Speed North, the Commission’s report on strategic improvements to transport connectivity in the North. However, before this Assessment the Commission has not previously considered HS2, as its remit excludes decisions that have already been made and spending that has already been committed, unless specifically requested to do so by government.

Interim report

In July, the Commission published an interim report, which covered rail and economic outcomes (which is summarised in chapter 2), the Commission’s methodology (which is summarised in chapter 4) and set out a series of questions for stakeholders. Responses to the questions are covered in box 1.1.

Box 1.1: Responses to interim report questions

The interim report set out questions for stakeholders on the proposed methodology for assessing the costs and benefits of different rail investment packages. The Commission held two roundtables with key stakeholders including government, transport bodies, rail interest groups and rail providers, as well as receiving 35 written responses to the questions.

Feedback was generally supportive of the methodological approach, although there was some concern that the approach may not capture potential transformational impacts from rail investments, particularly land values. The Commission’s methodology is intended to assess which rail investments are most likely to lead to transformational change but does not directly capture all the benefits that would arise from transformational change. The Commission’s methodology is covered in more detail in chapter 4.

Other key themes in the responses included:

- the need for Assessment to consider the ‘last mile’ of journeys and integration with local transport, which was particularly raised by local government respondents

- concern that small or underdeveloped schemes would be out of scope, meaning that proposals of significant local importance would not be included

- some opposition to the proposed approach to freight, particularly not assessing it under economic growth and not considering projected increases in rail freight volumes

- that a degree of uncertainty can be mitigated by government by setting out a clear long term pipeline of schemes

- a desire for greater clarity on the definitions being used for criteria, particularly amenity benefits and land values, and how different criteria will be measured and weighted against one another

- the need to take greater notice of demand forecasting in the analysis

- concern about the granularity of natural capital assessment tools.

Chapters 2 and 3 cover the need for the Integrated Rail Plan to avoid providing additional spending for rail at the expense of local transport. The interim report also stated that the Commission would not consider local (rather than strategic) rail schemes, and the Commission has followed this approach in the packages that have been developed for this assessment. Separately, some smaller schemes have been considered under ‘quick wins’ which can be delivered in the short term and may help to enable larger schemes to deliver benefits. Larger, strategic projects cannot be delivered to this timescale.

The Commission’s approach to freight is discussed further in box 5.4, and chapter 3 sets out the need for government to commit to a core long term pipeline of investment within an adaptive approach. The Commission has also published a modelling annex, which sets out more detail on the methodology, including the criteria used, alongside this report.13

The final Assessment

The Commission’s final Assessment sets out:

- key considerations for a successful Integrated Rail Plan

- an analysis of five options for programmes of rail investment, within three illustrative budgets

- options for accelerating the benefits of long term rail investments and identifying ‘early wins’.

While the Commission’s work on this Assessment has been informed by engagement with central government departments, as well as the Infrastructure and Projects Authority, the Commission’s conclusions have been reached independently. These conclusions represent the Commission’s judgement, informed by the evidence provided by stakeholders and its own analysis. The analysis informing this Assessment was finalised prior to the Spending Review and does not take into account any Spending Review announcements.

Stakeholder engagement

The Commission conducted an extensive stakeholder engagement process as part of this Assessment, including:

- a Call for Evidence, asking for evidence on the benefits and drawbacks of different schemes

- Interim Report questions on the methodology for assessing cost and benefits, as set out in box 1.1

- social research on the views and perceptions of rail of people in the Midlands and the North

- roundtable and briefing sessions with a range of expert stakeholders from local government, the rail industry, businesses, academia, environmental groups and other sectors.

Due to the ongoing Covid-19 crisis, this engagement has taken place virtually. The potential impact of Covid-19 on rail demand is discussed in chapter 2.

Responses to the Call for Evidence covered a wide range of different issues, proposals and potential investments across the Midlands and North in detail; a report summarising the key themes from those responses is being published alongside this report, as well as a summary of responses to the interim report questions.

A summary of the key themes from the Commission’s social research is included in chapter 2.

Rail and economic outcomes in the Midlands and the North

Despite being home to seven out of ten of England’s largest cities14 – many of which are not far apart – economic outcomes in the Midlands and the North of England are lagging behind those in the South of England. There is also a considerable difference between journey speeds in the Midlands and the North, and similar journeys in other countries and the South.

Rail cannot singlehandedly achieve the government’s objective of levelling up the UK. But it can improve productivity in dense city centres and deliver benefits to businesses from faster and more frequent connections between cities. The Integrated Rail Plan must address the existing issues in the Midlands and the North and focus on improving rail connections into dense city regions and between cities in the Midlands and the North, to have the best chance of supporting economic growth.

The Midlands and the North

The Midlands and the North are home to seven out of ten of England’s largest cities, many of which are relatively close together.15 In recent decades cities such as Manchester and Leeds have experienced rapid population growth in their city centres, mainly driven by young professionals. This has led to city centre populations doubling in size between 2002 and 2015, and they have continued to grow since.16

But economic outcomes in the Midlands and the North of England are lagging behind those in the South of England. Although cities such as Manchester and Birmingham are projected to see high employment growth and high congestion,17 productivity in cities in the North and the Midlands is still below the national average (although London and the South East are the only regions with above average productivity)18 and some smaller cities and towns, particularly those on the coast,19 have lagged behind. While other countries face persistent regional economic variation, the extent of regional variation within England appears to be unusually high compared to other countries.20

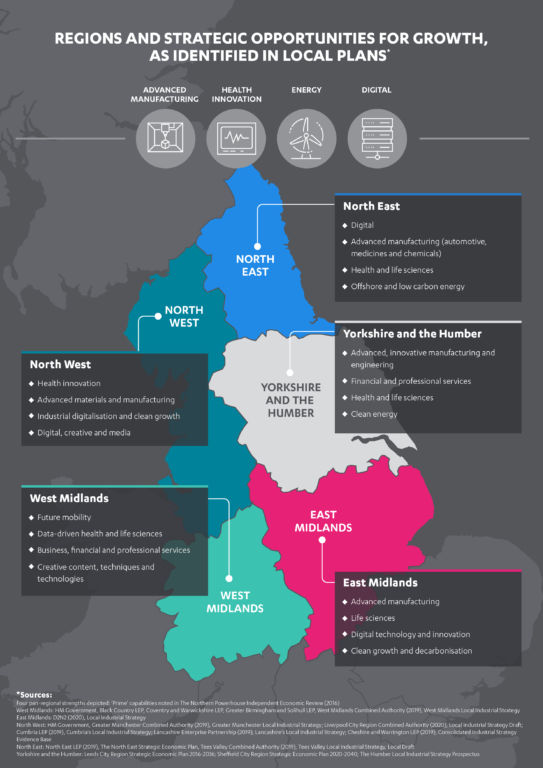

Each of the regions has different economic strengths and opportunities they wish to unlock to improve economic outcomes in the region; see figure 2.1. Many of these are high skilled, knowledge based sectors which particularly benefit from improvements to productivity in cities.21 The businesses and supply chains in these sectors will also gain benefits from increased connectivity.22 The Commission’s methodology assesses the potential benefits of a menu of options of rail investments in these areas and so packages that perform better against these criteria should support the regions’ economic strengths and opportunities.

Figure 2.1: Regions in the Midlands and the North – economic strengths and strategic opportunities

Only ten per cent of journey miles are made by rail.23 However, the benefits of rail investment do not just fall to those who use the railway. Rail investment also brings benefits to the cities it connects and the towns nearby.

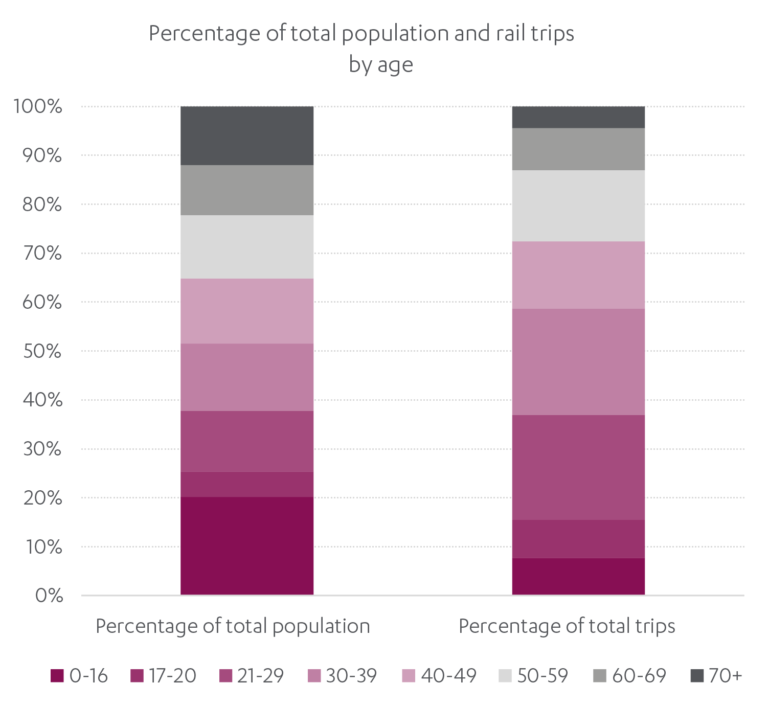

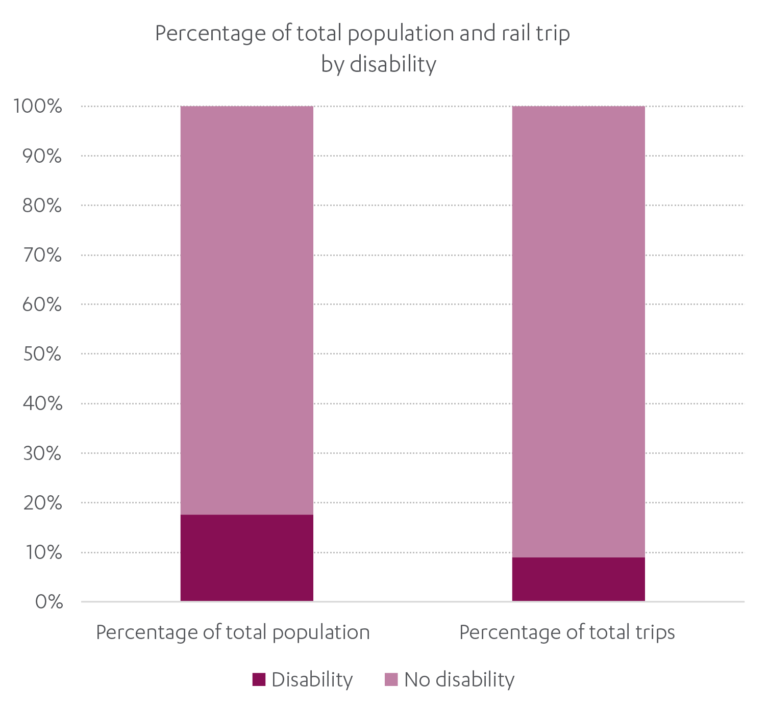

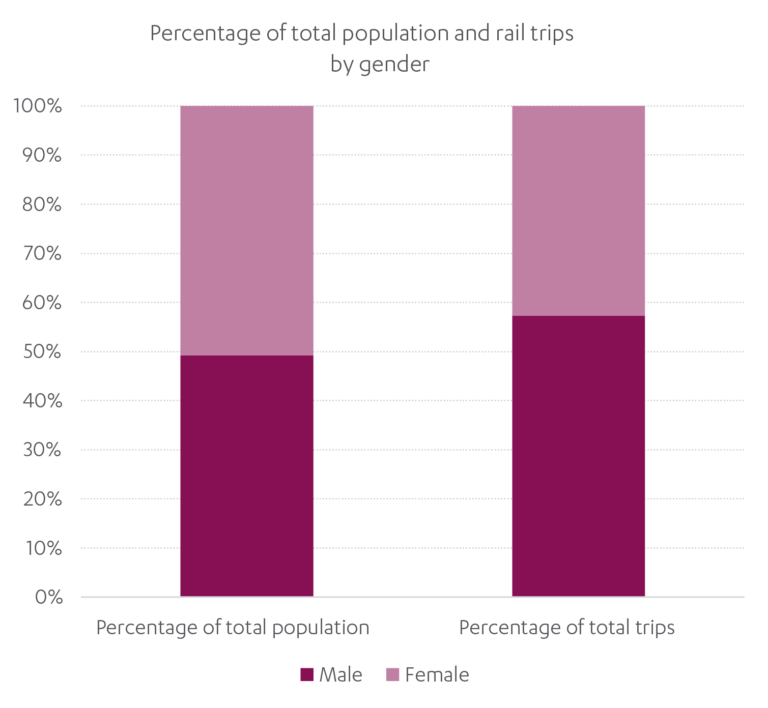

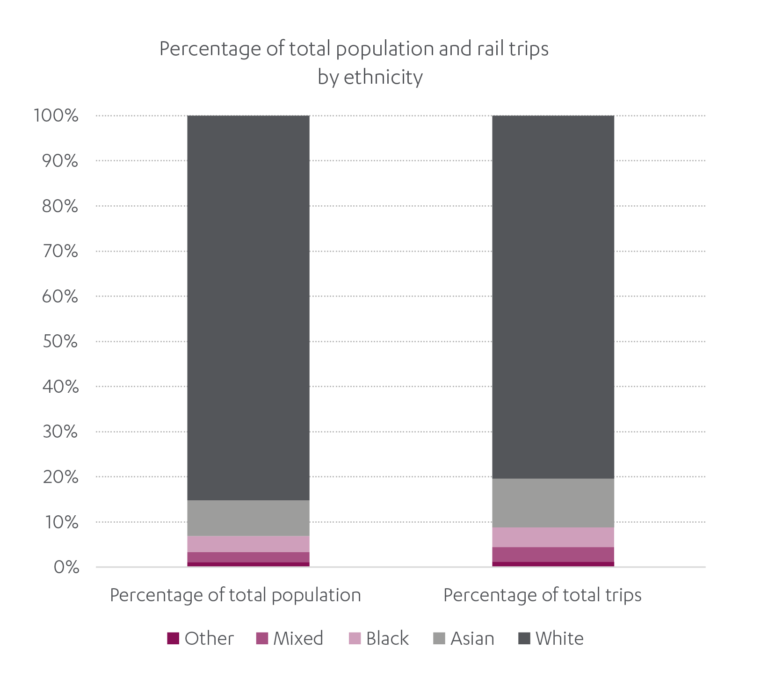

Who uses the railway in the Midlands and the North?

As well as testing the public’s preferences for rail investment, the social research undertaken by the Commission to inform the assessment also provided a picture of rail use in the Midlands and the North. The research found that only a minority of people use rail as their main mode of transport, frequent rail users are more likely to earn higher incomes and work in managerial and professional occupations, rail use is more common among those living in urban areas, and rail use is higher amongst the working age population, with younger people more likely to use the train. This is consistent with the analysis in the Commission’s interim July report.

These characteristics are aligned with the characteristics of rail users across England. Other characteristics of rail users across England are set out in figure 2.2.

Figure 2.2: Railway use in England24

Who will share the wider benefits of rail investment in the Midlands and the North?

The economic benefits of rail tend to fall primarily to cities, which generally have a more diverse ethnic makeup than rural areas.25 The population of cities also tends to be younger – the population in major cities in the Midlands and the North is younger on average than the population as a whole.26 Figure 2.3 sets out distributional data about the people who live in and around key cities in the Midlands and the North.

Figure 2.3: Distributional data for travel to work areas (TTWA) in the Midlands and the North27

| % of TTWA Population | Age | Ethnicity | Disability | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age 0 to 19 | Age 20 to 29 | Age 30 to 44 | Age 45 to 64 | Age 65+ | White | Mixed | Asian | Black | Other | Disability | No Disability | |

| Manchester | 25% | 14% | 21% | 25% | 15% | 85% | 2% | 10% | 2% | 1% | 19% | 81% |

| Liverpool | 23% | 15% | 19% | 26% | 17% | 94% | 2% | 3% | 1% | 1% | 23% | 77% |

| Birmingham | 26% | 14% | 20% | 24% | 17% | 74% | 3% | 17% | 5% | 1% | 19% | 81% |

| Leeds | 26% | 15% | 21% | 24% | 15% | 79% | 2% | 15% | 2% | 1% | 17% | 83% |

| Nottingham | 23% | 14% | 19% | 26% | 19% | 89% | 3% | 5% | 2% | 1% | 19% | 81% |

| Sheffield | 23% | 14% | 19% | 25% | 18% | 89% | 2% | 5% | 2% | 1% | 20% | 80% |

| Newcastle | 23% | 14% | 19% | 27% | 18% | 95% | 1% | 3% | 1% | 0% | 22% | 78% |

Rail in the Midlands and the North needs improvement

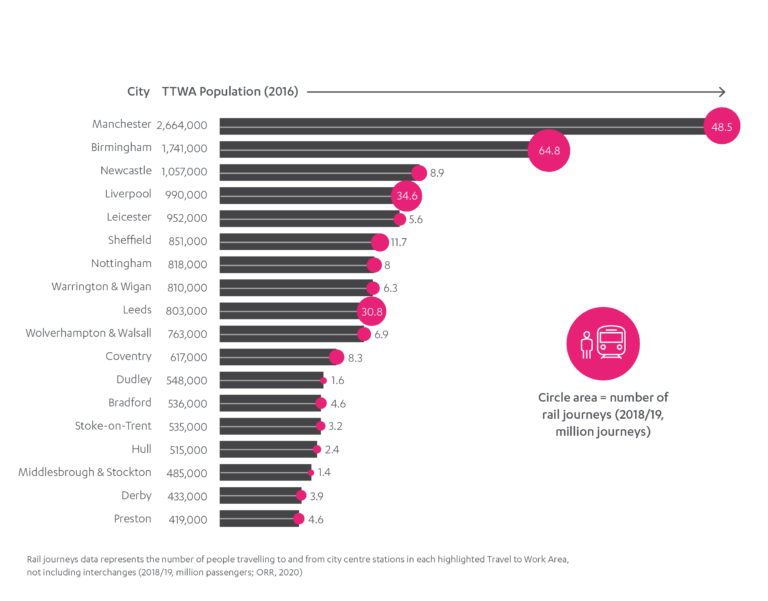

Major cities in the Midlands and the North are experiencing capacity issues

Alongside the growth in city centre living, many large cities in the Midlands and the North were experiencing very high volumes of rail journeys in and out of city centres before the Covid-19 pandemic see figure 2.4. And this number appeared to be growing – between 2010 and 2019, passenger arrivals by rail during the morning peak increased 36 per cent in Manchester, 41 per cent in Birmingham and 19 per cent in Leeds.28

Figure 2.4: Rail journeys in cities in the Midlands and the North

Some of these cities, such as Manchester, Birmingham and Leeds, have had commuting capacity issues for several years, with peak morning trains operating with 2.6, 4.6 and 2.1 per cent of standard class passengers in excess of capacity in 2018. This has also become more of an issue in Nottingham in recent years.29

There are also congestion issues on the rail network. One of the benefits of HS2 is that it would free up train paths and platforms on the heavily congested East and West Coast Main Lines and the Midland Main Line.30

Rail services in the Midlands and the North can be slower than those in the South and other comparable countries

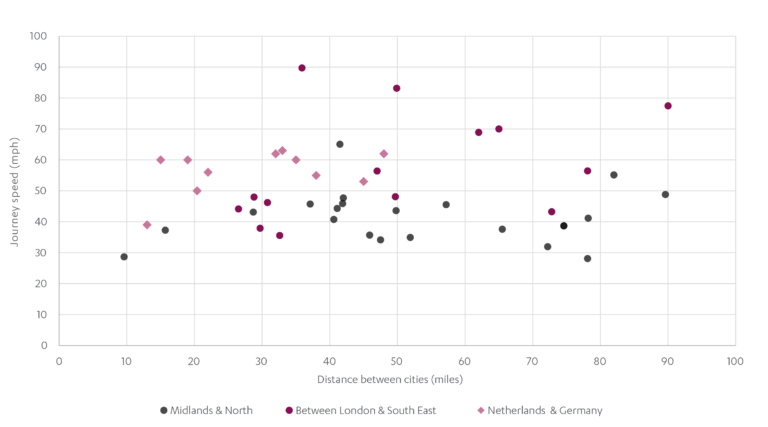

Rail journeys between major cities in the Midlands and the North also tend to be slower than those in London and the South East, and in regions with high productivity in other countries, particularly for shorter distances (see figure 2.5).

Figure 2.5: Rail journey speeds versus distance between cities: Key cities in the Midlands and the North, compared to London and the South East, and the Netherlands and Germany 201931

Furthermore, some train services in the North and the Midlands can be unreliable, with services including Northern, CrossCountry, TransPennine Express and Hull Trains performing worse than the national average for trains arriving on time in 2019-20.32 The issues with rail in the Midlands and the North were covered in more detail in the Commission’s interim report.33

The public see room for improvement in rail, but are doubtful that it can or will be delivered

The Commission carried out social research to support this Assessment, which aimed to understand what rail users value about the railways, identify barriers to using rail among non-users, establish public priorities for future investment and explore what might encourage rail use. The social research comprised:

- a quantitative survey of a representative sample of 3,000 adults in the North and the Midlands, including around 2,000 rail users, and around 1,000 people who had not used the railway in the last 12 months

- twelve online focus groups to understand the thoughts underpinning the survey responses.

The key findings from the social research included the following:

- Participants in focus groups were doubtful that new lines would or could be delivered: Participants in the focus groups favoured rail investments which felt tangible, including increased capacity and reliability, but not new lines, because they were sceptical about whether these would or could be delivered.

- Participants prioritised the minimisation of disruption for improvement works over completing work quickly: While minimising disruption did not score highly in priorities for improvement, the possibility of work taking place at night was well-received, with many saying that there are few night trains in the regions. There was also widespread cynicism that rail improvement works are ever completed on time, leading to participants being sceptical about delivery schedules.

- People use rail when it is convenient, and services are direct: The quantitative survey revealed rail users choose rail because of its speed and convenience and are more likely to live and/or work within walking distance of a railway station. Conversely, non-users do not use rail because it does not offer a simple route and is considered slow and inconvenient compared to other forms of transport.

- Participants did not prioritise further increases in train speed: In the quantitative survey ‘faster trains’ ranked eighth out of a list of 12 priorities for improvement. Rail users consider trains to be a fast means to travel and they do not prioritise increasing the speed of future journeys.

- Participants favoured increased rail capacity: All survey respondents expressed an overall preference for increased capacity (which they likely understood as reduced crowding and more available seats) and reliability on the rail network, well ahead of other areas for investment.

- Participants struggled to see the connection between rail and economic growth: Arguments related to ‘boosting local economies’ were generally met with confusion by participants.

The Integrated Rail Plan must improve services for rail passengers in the Midlands and the North

Improvements to rail services in the Midlands and the North are needed to accommodate long term growth in the number of people commuting by rail. While providing additional rail capacity would reduce crowding on trains in the short term, existing crowding demonstrates that increased capacity would be valuable (people are already willing to board crowded trains for these journeys) and likely to be filled over time. Although this means crowding is likely to increase again in the long term, without additional capacity being used the economic benefits of rail investment will not be delivered.

Rail can improve economic outcomes

The Integrated Rail Plan is intended to support the government’s strategic objective of ‘levelling up’ by contributing to economic growth in the North and the Midlands.

The Commission’s recent discussion paper Growth across regions sets out three different pathways by which infrastructure investment can help to achieve economic outcomes in different regions:

- universal provision – setting common/minimum standards for infrastructure services where appropriate to reduce differences in access and opportunity across the UK

- addressing constraints to growth – enabling future growth in congested places by investing in capacity upgrades, with the expectation that this will also benefit surrounding areas

- contributing to transformation – prioritising infrastructure investment alongside wider polices to increase growth in low productivity places.34

The most appropriate pathway and type of infrastructure measures will vary according to the characteristics and strategic needs of different places. Providing faster or more frequent journeys is the clearest way rail investment can address constraints to growth. However, with the right package of complementary investments rail can also contribute to transformation. This pathway has the biggest impact on growth where it is effective but is also the highest risk strategy.

Rail can contribute to improving economic outcomes by:

- increasing the density of clusters of people and businesses,35 which can increase the productivity of existing firms and workers in cities, improve the environment for innovation and make cities more attractive for businesses and workers to locate in

- facilitating ‘trade’ between cities by providing faster, more frequent rail connections to businesses, enabling them to source a wider range and better quality of inputs to their supply chains, and increasing the size of the market any one business can access, allowing successful firms to grow, and encouraging workers to specialise and upskill36

- making places more attractive to live and work in

- encouraging commercial investment by signalling that an area is worth investing in.

These benefits tend to arise from rail investment that supports transporting people into dense city regions and providing high speed rail links between cities, where rail can be faster or more convenient than cars for many people.

Good rail connections into and between cities tend to be present in comparable groups of cities in other countries. While cities in the Midlands and the North have below average productivity, strong regional centres in other countries, such as the Randstad in the Netherlands and the Rhine-Ruhr region in Germany, have productivity above their national averages.37 This is driven in part by strongly performing cities within those regions, but those cities are also well-connected by rail links which tend to be faster and, crucially, more frequent than those between Northern cities in the UK (see figure 2.5).38 None of England’s economic comparators, with similar geography, have poor rail accessibility between cities.39

To contribute successfully to a wider strategy of tackling regional variability, rail investment should focus on journeys both between cities and into city centres from their surrounding areas. Although major rail interventions can most successfully support big cities, successful cities can improve the prospects for towns in the vicinity: most successful towns in England are close to successful cities.40 41 Rail improvements for big cities can benefit cities and towns nearby – for example, improving links between Manchester and Leeds will also improve connectivity for places like Huddersfield and Bradford, and places like Solihull will benefit from better services to and from nearby Birmingham.

Rail alone may not be enough to deliver economic transformation

Rail investment alone is unlikely to be enough to transform the economic outcomes of a region, city or a town. Large scale rail investment is a strategic bet. However, there are things that can be done to increase the likelihood of rail investment contributing to economic transformation. More concentrated interventions have a better chance of supporting economic transformation than a series of small changes. And a wider set of complementary policies are also needed to address other issues, such as skills and urban transport, that are necessary for economic transformation.

As part of a combination with other policies, rail is much more likely to contribute to the type of non-linear benefits that true transformational change can bring. It is difficult to quantify these benefits, or the tipping point at which they will occur. But delivering the right set of interventions together, rather than in isolation, should increase the chance of these non-linear benefits occurring.

Investment needs to be at scale

Where rail can support growth, the direct benefits are modest compared to the size of local economies. Investment must be concentrated and at scale for it to have the best chance of contributing to growth in cities.42

Enabling places with low productivity to ‘catch up’ with more successful places requires a step change in growth that outpaces the more successful places for a sustained period, which is very hard to achieve. But, according to the Industrial Strategy Council, “the evidence also clearly suggests that reversing the cycle of stagnation is possible provided policy measures are large-scale, well-directed and long-lived.”43

The analysis shows that under all the packages Birmingham, Manchester and Leeds are generally the largest beneficiaries. This is consistent with the Commission’s view that levelling up and increasing economic growth in regions requires economic growth in the major cities. While the relationship is complex there is a strong linkage between highly performing major cities and highly performing regions.

Rail needs to be combined with other policies

Regional disparities are caused by many interrelated issues, including skills, that would need to be addressed to achieve economic transformation. Other factors, such as the availability of good housing, schools, urban transport, city services such as shops and hospitals, low crime rates and good governance also affect outcomes, such as where people choose to live.

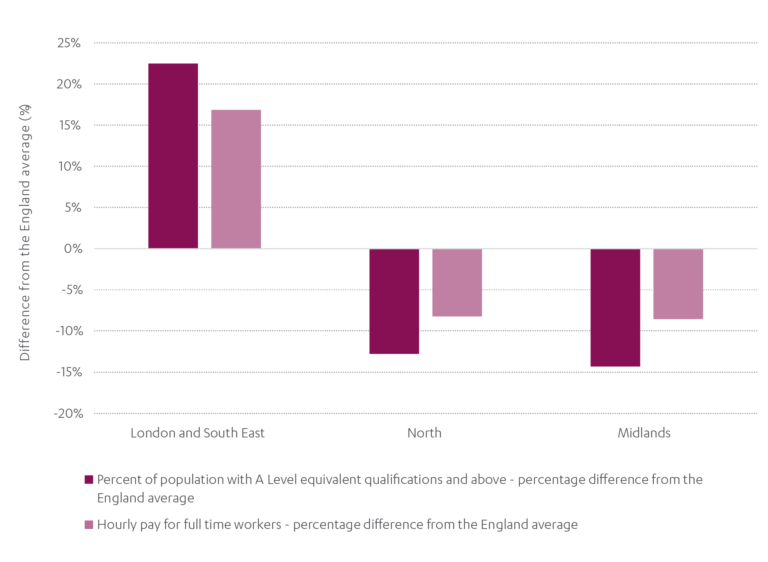

Figure 2.6: Skill level and earning potential for London and the South East, the Midlands and the North, 201944

Other measures that support growth can increase the likelihood of rail investment delivering the intended benefits, and rail investment can in turn encourage other investment and contribute to the success of these other measures, contributing to a positive cycle. Therefore, it is vital that when and where rail investment happens it is coordinated with, and enables, local plans to address other issues and support growth, in order to maximise the benefits of the rail investment.

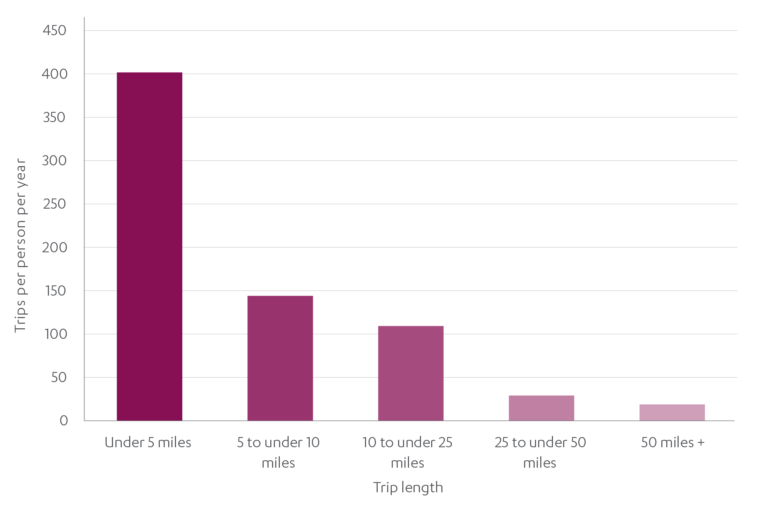

Urban transport is particularly important, as urban transport networks underpin commuter journeys that create deep labour markets and enable people to access cultural and leisure activities. Most journeys are short, relying predominantly on urban transport networks (see figure 2.7). Infrastructure to support public transport in growing and congested cities offers some of the highest returns for transport investment.45

Figure 2.7: Average number of trips per person per year by trip length, 201946

For example, West Yorkshire Combined Authority are developing mass transit options for the Leeds City Region, which is often characterised as the largest metropolitan area in Europe without any form of light rail or underground rail network.47 Delivering a mass transit system for Leeds could likely be done sooner than the current lead-in times for major rail projects and could enable passengers to see improvements faster.48 Box 3.1 covers urban transport strategies.

Rail can also be an anchor for investment

Rail, particularly in and around new railway stations, can also act as an anchor investment, signalling to the market that the location is worth investing in because other people or businesses are also likely to move there. This helps to solve coordination problems where the value of private sector investment depends on other investors making similar choices.49

New and major redevelopments of stations are the most visible sign of this and can help to create further development opportunities where land in city centres is scarce and expensive. Development plans are already in place for new HS2 stations. For example, the Curzon HS2: Masterplan for Growth is aiming not only to increase commercial floor space in the centre of Birmingham but also to add 4,000 new homes, and the plan claims that it will increase Birmingham’s GVA by £1.4 billion per year.50

Not only does this provide an example of rail’s ability to act as an anchor, it also shows that the signal provided by stable future commitments can enable benefits to be delivered well in advance of rail investments themselves coming online. By providing an anchor, rail can help to enable the broader set of policies needed to create the potential for transformational change.

The benefits of rail investment depend on certain assumptions

In order to think that investing in rail is a good idea, government will need to consider that the current evidence supports the following assumptions remaining true:

- The economy will remain focussed on cities – Rail is predominantly effective for transporting large numbers of people into and between dense city centres. Nowhere outside of cities and their surrounding areas has the high densities of people using rail that would justify its high costs. Since the 1990s cities have grown as centres of employment and entertainment, making rail more important. This is likely to continue if the following hold true:

- Covid-19 or other shocks do not cause people to abandon cities over the long term

- there continue to be benefits to many UK businesses from being located close to other businesses, which is particularly important in highly skilled services, which the UK currently specialises in, but less important in other areas such as agriculture

- that people continue to go to cities for leisure, retail and entertainment.

- Other technologies will not replace rail – Technologies usually go out of use because they are replaced by something better. Government would need to consider that rail will not be replaced either because digital connectivity replaces face to face communication or because alternative transport technologies offer a cheaper and more convenient way to move into and between dense city centres.

- Complementary policies in the North and the Midlands work – Rail is necessary but not sufficient to deliver economic transformation. It needs to form part of a wider economic strategy for levelling up the Midlands and the North. Government would need to consider that the wider economic strategy will work for rail investment to deliver the intended benefits. Rail use will also be higher if the economic strategy works, as people in the highest income band are the biggest users of rail,51 and because rail is a complement to highly skilled industries, as it provides specialist services with a wider potential market and employment pool.

- The economy does not stagnate – Government would need to consider that the economy will grow on a national level over the coming decades. Rail use will grow if the economy does well, for the same reasons set out above.

- The working age population does not fall – The last 20 years have seen large increases in the UK’s working age population, partly due to immigration; however, EU exit and low birth rates mean this trend may not continue. Since rail is mainly used for commuting to work,52 a fall in working age population could also lead to a fall in peak rail use and undermine the case for additional capacity.

Next Section: A core pipeline and an adaptive approach

The Integrated Rail Plan is an opportunity for government to bring clarity, stability, and pragmatism to future rail planning. But that doesn’t mean committing to every major project – it is also an opportunity for this government to break the cycle of committing to major rail schemes, underestimating the costs and ultimately having to reopen plans or find additional funding. The Plan also needs to form part of a wider economic strategy.

A core pipeline and an adaptive approach

The Integrated Rail Plan is an opportunity for government to bring clarity, stability, and pragmatism to future rail planning. But that doesn’t mean committing to every major project – it is also an opportunity for this government to break the cycle of committing to major rail schemes, underestimating the costs and ultimately having to reopen plans or find additional funding. The Plan also needs to form part of a wider economic strategy.

The Integrated Rail Plan must be well costed to provide greater certainty and avoid overspends. If the Plan is to have the best chance of delivering economic transformation, investments must be concentrated and at scale in the places where they are most valuable and form part of a wider economic strategy.

Government should commit to a core pipeline of rail investments that align with its strategic objectives. If further funding is available and can be committed, government could add further schemes or enhancements that build on this core pipeline to deliver the strategic objectives. Further enhancements or additional schemes should only be delivered where:

- it is clear the pipeline of core schemes is delivering on time and to budget

- complementary investments are being made that increase the likelihood of rail investments contributing to transformation

- they are sufficiently developed with robust cost ranges.

The Plan should not overpromise

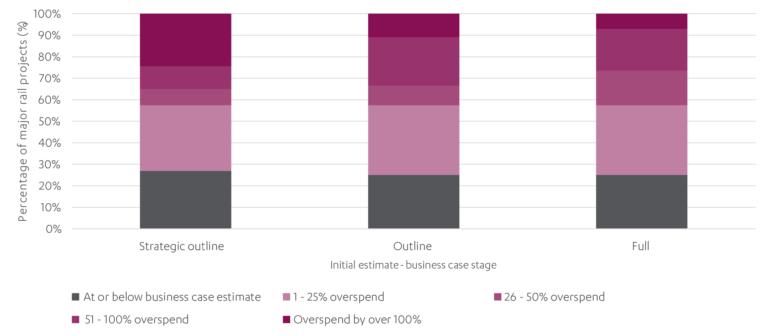

There is a long history of overspends and cost increases on major rail projects.53 The cost of electrification of the Great Western railway grew by £2.4 billion between 2013 and 2016.54 Costs for the West Coast Main Line upgrade rose by £7.8 billion.55 The central section of the Elizabeth line was initially planned to open in December 2018, but this has since been delayed to 2022, and the project could cost £1.1 billion more than the financing package (of £17.6 billion) agreed in December 2018.56 As set out in the Oakervee Review, the total costs of HS2 were estimated at £80.7-87.7 billion, against a budget equivalent to £62.4 billion.57 Cost increases and overspends can lead to schemes being revised or descoped because costs have increased and plans are no longer affordable within the funding available.

Cost overruns are driven by several factors, including underestimation of the cost and quantity of materials required, and changes in standards or scope during construction, planning and design. However, cost estimates for projects continue to insufficiently consider these possibilities, in part down to optimism.

It is standard in the rail industry to have a 64-66 per cent uplift applied to the ‘base’ cost estimate when a single option is selected. Research carried out for the Commission suggests that, for certain projects, a significantly higher uplift to the base cost estimate may be more appropriate.58 Given this uncertainty about costs, the Commission has included potential cost ranges for each package.

Figure 3.1: Outturn costs of major rail projects compared to cost estimates at different business case stages59

It is better that government promises less and eventually delivers more, than that places in the Midlands and the North are promised projects that eventually have to be cut, delayed or significantly descoped due to cost overruns. The government should develop realistic costings in the Plan, considering the potential for current costs and lead times to be underestimated and having regard to findings from the Infrastructure and Projects Authority. This may mean more time is needed to develop the Plan, but this will cause less delay in the long term and provide greater certainty and stability for stakeholders.

While better cost estimation would help reduce the likelihood of overspends, it is also important that projects stick to budget during construction. If one project runs over budget, then others in the pipeline may no longer be affordable. Government therefore needs to ensure that the right processes are in place to manage costs and that difficult decisions about scope are made to avoid cost increases.

There is also a clear tendency for the timescale for schemes to be underestimated as well as costs. On average, construction schedules for rail projects have ended up being between a quarter and a third longer than predicted, although the overrun distribution differs quite a lot between project types.60

The Plan should maximise the benefits that rail can deliver

As set out in chapter 2, rail can contribute to economic outcomes, but rail alone is not necessarily enough to deliver economic transformation. To give the best chance of delivering economic transformation rail investment should be concentrated and at scale, and form part of a wider economic strategy.

Investment should be at scale

As set out in the previous chapter, rail investments have the best chance of contributing to economic outcomes if they are at scale. Practically, this means:

- investment should be targeted at places where rail is most valuable, for example where there are already capacity constraints – rail capacity will be most in demand where there are already economic opportunities in the cities that people want to access, and this may be where complementary factors are already in place

- rail investment should be focussed at scale on specific places – if investment is spread thinly between different places the benefits, if they are achieved, will likely be smaller.

The Plan should form part of a wider economic strategy including local transport

As set out in the previous chapter, to have the best chance of realising their benefits rail interventions should form part of a wider economic strategy.

The Plan should form part of a comprehensive strategy to make cities attractive places to live, work and invest in, alongside other factors including skilled employment, urban transport, good governance and local decision making, which should include local strategies (see box 3.1).61 To be successful, the strategy will need to be comprehensive and recognise the scale of the regional variation challenge and its self-reinforcing nature.

Box 3.1: The Integrated Rail Plan and urban transport strategies

In the National Infrastructure Assessment, the Commission recommended that urban authorities should be given the powers and funding they need to pursue ambitious integrated strategies for transport, employment and housing. These strategies should enable cities to make the most of national rail schemes, such as those in the Integrated Rail Plan, ensuring they are integrated with local transport networks, and support housing and employment. As part of that recommendation, the Commission advised that £43 billion of additional investment should be made available between now and 2040 for major urban transport projects in the fastest growing, most congested cities, which could cover interventions such as delivering a mass transit for Leeds.

Both HS2 and Northern Powerhouse Rail will interact with existing local transport strategies along their routes. Examples of these include:

- the Sheffield City Region Transport Strategy62

- West Midlands Combined Authority’s Movement for Growth strategy63

- West Yorkshire Combined Authority’s Transport Strategy 204064

- Greater Manchester Combined Authority’s Transport Strategy 2040.65

Local transport plans in Liverpool, Tees Valley, Derby and Cheshire East are also all closely linked to major rail schemes.66

Integrated infrastructure strategies will help ensure that cities in the Midlands and the North can maximise the benefits of the Integrated Rail Plan and will form an important part of delivering a transport network that can support transformational benefits across the country.

An adaptive approach can address these challenges

Even with a well costed Plan that concentrates investment and forms part of a wider economic strategy of complementary policies, there will still be inevitable uncertainty. Costs may still increase due to unforeseen factors. Other projects may overrun and delay construction. The location or size of capacity demand may change. Complementary policies may not be delivered on time or may not deliver economic transformation.

Therefore, while it does make sense to deliver rail investment to address existing issues and contribute to supporting economic outcomes, this does not mean investing in every major project proposed. The current total estimated capital cost of HS2, Northern Powerhouse Rail, the Transpennine Route Upgrade, Midlands Engine Rail and other interventions such as decarbonisation and digital signalling is in the region of £140 – 185 billion in 2019/20 prices between 2020 and 2045.67 Government should exercise some caution, especially on projects where the costs and benefits are less certain.

An adaptive approach can enable government to address this uncertainty. Government could initially set out a commitment to a core set of affordable, stable investments, with a clear funding profile and rigorous costings, that should not be reopened. This will provide stability for stakeholders, enable local bodies to make and enact plans and help provide investors and developers with the confidence to bring forward their own investments, meaning the benefits from rail investment will be seen sooner.

There could then be clear options to either enhance these schemes or add further schemes later. If further funding is available and can be committed, the decisions to progress further enhancements or schemes should be taken within a set framework. For example, only if:

- it is clear the pipeline of core schemes is delivering on time and within the budget