An opinion piece by Caroline Bryce, Asset Management Adviser at Mott MacDonald and member of the Commission’s Young Professionals Panel.

The UK announced its sixth Carbon Budget earlier this year, committing to reducing emissions by 78 per cent by 2035 compared to 1990 levels. The government expects to achieve this target through investing and capitalising on new green technologies and innovation, while maintaining people’s freedom of choice, including on their diet. That is why the government’s sixth Carbon Budget figure of 78 per cent is based on its own analysis and does not follow each of the Climate Change Committee’s specific policy recommendations.1

Last week the government announced its Transport Decarbonisation Plan (TDP). This is an important step for the UK as Transport2 is the largest source of carbon dioxide emissions, accounting for 34 per cent in 2019,3 the majority of which was from road transport.

When the government set out the decarbonisation of transport challenge, it aspired to make public transport, cycling and walking the natural first choice for journeys. It’s an important point to infrastructure planners – we do need to make it easier for people to make low carbon lifestyle changes. So does the transport decarbonisation plan provide a clear roadmap to enable the UK to meet its net zero target by 2050?

Electric vehicle infrastructure

The government had said it will ensure the UK’s charging infrastructure network “meets the demands of its users”. Overall, £1.3bn will be invested over the next four years to accelerate the rollout of chargepoint infrastructure, including funding pots available to upgrade the grid capacity and installing charging points within communities and service stations.

The TDP levels up the government’s commitment to phasing out new petrol and diesel cars by 2030 by proposing a similar ban on new large HGVs by 2040, which is now out for consultation. Both deadlines are not that far away and this infrastructure delivery is needed to improve public perceptions on whether electric cars are a viable option outside of cities, in order for the public to start making an organic move to electric vehicles.

Shift journeys from road and air to rail

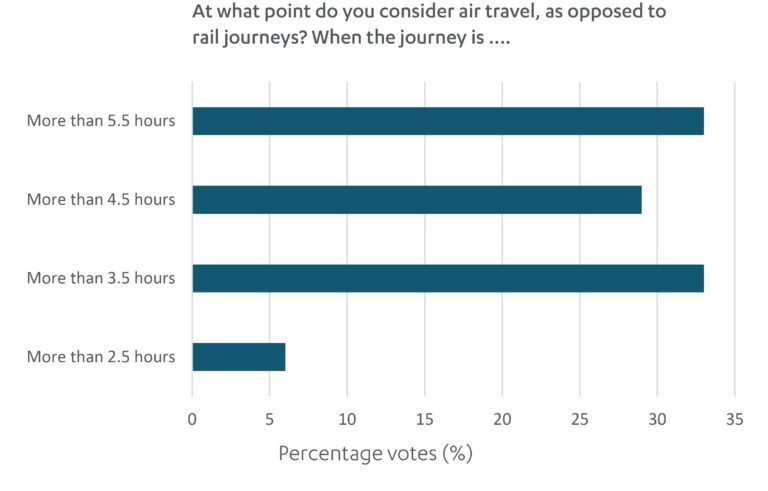

Back in April, Martin Lewis polled his followers on Twitter asking whether they would back a similar move to the French government, which banned domestic flights where an alternative train route was available and journey times were under two and a half hours. The result was overwhelmingly positive: 79 per cent in favour. When the Young Professionals Panel polled our own followers on LinkedIn, the cumulative majority said they considered the train over flights where the rail journey was less than 4.5hrs, similar to the initial recommendation from France’s Citizen’s Convention on Climate.

While the TDP does not seek to ban domestic flights, it does commit to building extra capacity on our rail networks to encourage the move. Domestic flights only account for one per cent of the 34 per cent the transport sector contributes to the UK’s greenhouse gases. Decarbonising rail, buses and private cars should therefore be higher on the agenda.

The government has a real opportunity through the creation of Great British Railways to influence passenger behaviours, by making rail fairs more competitively priced. The government consulted back in March on cutting air passenger duty on domestic flights, which seems the exact opposite to the ‘polluter pays principle’ and what is needed until a ‘jet zero’ solution is available. Instead, the government should be looking at reducing the prices on long haul rail journeys to make them more competitively priced, to encourage the shift from air and road travel.

Decarbonisation of the railways

Alongside the plan, the government published a Rail Environment Policy statement, which sets the ambition to achieve a fully zero emission rail network by 2050. The TDP includes plans to phase out all diesel trains by 2040, the majority of which will be achieved through electrification, and some through battery and hydrogen technologies.

Whilst many will be disappointed that the integrated rail plan remains “to be published soon,” the TDP will allow the energy sector to begin to respond and plan to accommodate for the increased electricity demand once the next phase of electrification projects pledged is announced.

Local public transport and active travel

The TDP states we must “avoid a car led recovery” and decarbonisation of private vehicles does not resolve congestion on our roads. It is encouraging to see the plan is looking to take a more full-journey approach to transport planning, looking at how we can enable the public to get to and from stations by cycling, walking or even e-scooters.

The TDP reinforces funding already pledged for creating better cycle and walking networks, to make the most of the momentum generated during the pandemic restrictions (cycling rose by 46 per cent last year4), with the aim that half of all journeys in towns and cities will be cycled or walked by 2030.

Some will be disappointed to see the government’s recommitment to its £27bn road investment strategy. The Welsh Government in contrast has decided to pause its own strategy to review each of its scheme’s environmental impact. However, the TDP does pledge to review the National Networks Policy statement which underpins all road investment in the UK.

The TDP also includes support for further light rail schemes in enabling local transport solutions after success in Greater Manchester and Nottingham in reducing traffic volumes.

The TDP reinforces its commitment made in Bus Back Better (the Bus strategy for England) to transform the sector by increasing frequency, reliability, affordability and user-friendliness. Approximately three per cent of the UK’s greenhouse gas emissions in 2019 came from buses and coaches. The government is currently consulting on the end date for non-zero emissions buses and is committed to deliver the first all-electric town or city bus service, but there is no date stated by which to achieve this.

Conclusions

Covid-19 has certainly caused a step change in how we use our transport systems (see chapter 1 of the Commission’s recent paper on Behaviour change and infrastructure beyond Covid-19) and it makes long term transport planning extremely difficult when no one really knows the extent to which homeworking and flexible hours will stay.

The plan targets the right areas to decarbonise transport in the UK. However, many of these plans are overdue and we are often left waiting for another strategy or plan for further details and clarity on the timetable for infrastructure delivery.

Much of the plan depends on our national grid being zero emissions, a target we have only achieved for 68 days in 2020. If all cars became electric in the UK, we would need approximately 75TWH additional energy in the grid, which would equate to a 20 per cent increase in the UK’s electricity production, even before we account for changes in rail, buses and other industries all racing to net zero.

A systems approach is needed to decarbonise infrastructure in the UK. All parties (including cross-sector) from regulators to suppliers need to understand their roles in this plan.

The plan lists a number of commitments and the short term funding pots allocated to them, with some sections providing more detail than others. But I can’t help but feel pessimistic about the vision without the delivery plans to back it up. The public and the market both need confidence more than ever if they are going to make the private investment to buy an electric car, or add a future new commercial fleet into their business plans.

As the news rolls in of extreme heatwaves in North America and flood events in continental Europe, the impact of climate change grows ever starker. Yet the pace for decision making and taking action doesn’t seem to match the severity of the crisis. The plan may outline the checkpoints the transport industry needs to reach, and a series of deadlines to meet, but the route to follow is less defined, leaving the industry still waiting for directions.

The views expressed reflect those of the author rather than the Commission.