Managing uncertainty in the second National Infrastructure Assessment

This paper considers how infrastructure policymaking can best deal with an uncertain future.

Executive summary

Infrastructure projects must be designed to be useful and effective over the course of their lifetimes, withstanding as far as possible the changes that occur over the years, decades, or even centuries of their use. Future projections and forecasts – for example, for the economy, population and environment – are often used to help plan infrastructure. But this has limited benefit in a highly uncertain world. Good infrastructure policy must instead be robust to a wide range of possible futures, both at a project and portfolio level.

Good infrastructure policy must be robust to a wide range of uncertain future events, to ensure that decisions taken now really do serve the needs of people in the future. When infrastructure policy is designed for a “central scenario” it targets a future that is unlikely to happen with actions that are unlikely to be right. Significant opportunities can be missed, and avoidable risks may materialise.1 This is a common failing of UK infrastructure policy and contributes to the country’s experience of start-stop infrastructure delivery. From their earliest stages policies must work in as wide a range of scenarios as possible.

The challenges presented by uncertainty are exacerbated by long lead times and the long lives of infrastructure assets.2 Even when sophisticated analysis of future uncertainties is done, it may be disregarded or misunderstood by the time options are put in front of decision makers.3

In the face of genuine uncertainty, processes for responding to unforeseen events are more important than increasingly sophisticated attempts at predicting them. Where prior experience can help us understand the likelihood and impact of future events, it is possible to take a risk management approach. But not all events have a recent historic parallel. Instead, sequencing projects, learning from the first steps, and adapting in subsequent ones (“adaptive frameworks”) can allow flexibility to respond to the unexpected.

Infrastructure proposals should be designed to perform well across many different scenarios of the future. Adaptive frameworks can address circumstances where uncertainty may resolve itself over time, providing forward momentum around a stable core while maintaining flexibility to follow a range of different adaptive pathways. Infrastructure plans as a whole should not be unduly biased towards one, or one set of, possible futures: they should seek to balance a set of robust investments, strategic bets and hedging activities that help to seize unexpected opportunities and insure against bets going wrong.

A pragmatic approach backed by experience

Designing for multiple possible futures significantly increases the chance that infrastructure will be useful and effective through its whole life. This can involve designing for one scenario and adjusting to improve performance in others, or looking for the common elements of policies that are optimised to each scenario in turn. The Commission’s study Engineered Greenhouse Gas Removals discussed the need for a strategic commitment to engineered removals because, in most scenarios, some engineered removals are needed to meet net zero.4 Rail Needs Assessment for Midlands and the North identified a stable core of investments that are likely to perform well in a wide range of possible futures.5

Not every project or policy will pay off in every scenario, so it is important to ensure a balance of risks across a wider portfolio. To do this, there must be a clear framework for deciding whether a project is part of a stable core of investment, a strategic bet or a hedging activity. The nationwide rollout of full fibre can be viewed as a strategic bet, whilst some major road schemes that are consistent with net zero have characteristics that place them in the stable core. Hedging activities are harder to identify in the infrastructure sector but are more common in military6 and public health sectors where resources are invested in preparing for inherently unpredictable events.

Adaptive frameworks are particularly useful for making firm delivery commitments in the face of an uncertain future. In some cases, it will be possible to incorporate flexibility for the future and, in others, to simply avoid closing down options earlier than necessary. The first Assessment discussed adaptive approaches to flood defence infrastructure: the Commission recommended flood defences are not built higher than needed for a world that is 2 degrees warmer, because they can be added to incrementally.7

The experience of high speed rail in France can be viewed as a successful adaptive approach to infrastructure planning. The first line was approved in 1978,8 and the second was announced when the first had been successfully delivered at an acceptable cost; only once the second line had opened did the French Government make a strategic commitment to a much larger high speed network.

The right approach to managing uncertainty depends on the specific policy, and a detailed understanding of what the future could look like. Developing a wide range of reasonably plausible scenarios of the future is an important but limited part of this. Many events could still lead the future outside this range and policymakers should be challenged to explore what future conditions would make their proposals unviable or unnecessary.

Scenarios should be based on relatively few key drivers, keeping the analysis simple and honest about the true scale of future uncertainty. The rest of the paper describes practical steps to do this.

A simple and honest approach to demand scenarios

Scenarios describe the possible future context within which infrastructure policy should be made. This is distinct from “policy pathways” towards a specified policy goal, which would capture the effects of new infrastructure policy.

The Commission has looked at work published by other organisations to understand the full range of demand scenarios relevant to its sectors and will seek to reflect this range in its own analysis for the second Assessment. Scenarios relevant to the Commission’s sectors are routinely published by industry, government and academia. They are often based on large and complex models and between them represent fairly wide but reasonably plausible ranges.

In reflecting the ranges produced by other organisations, the Commission does not need to accept the input assumptions used to generate them. Any given level of demand can be achieved by many different combinations of input assumptions. Describing the full range of possible future scenarios for demand is far more important than the precise combination of inputs that generated each scenario.

For illustrative purposes, this report presents the findings of its scenarios review in relation to electricity demand and road demand. Trends in electricity demand illustrate many of the changes expected across the wider energy sector and road demand is such a significant part of transport that it tends to dominate trends here. The scenarios review for these two sectors found:

- UK electricity demand could rise from around 300 TWh in 20229 to a range of 560-890 TWh by 2050.10 The wide range is driven by uncertainty about the generation mix (which affects the costs of electricity) and key policy choices over the role of electricity in decarbonizing transport and heating.

- Demand for road transport in England could remain at similar levels to today, around 300 billion vehicle miles,11 or rise to as much as 450 billion vehicle miles by 205012 Most scenarios foresee an increase as the population and economy grow and electric cars make travel cheaper, but it is possible to imagine a world in which the historic link between economic growth and transport demand is broken and a significant shift away from commuting following the Covid 19 pandemic helps to keep demand steady. Transport demand is currently subject to particularly high levels of uncertainty because travel patterns changed significantly during the pandemic.

Understanding the scale of future uncertainty

The major drivers of infrastructure demand and supply have evolved significantly since the first Assessment and illustrate many of the challenges associated with predicting the future. This paper revisits work on population, economic growth, technology and environmental change, to demonstrate the need to design for a wide range of scenarios.

Projections of population and economic growth have been revised significantly downwards by the Office for National Statistics and the Office for Budget Responsibility. The most recent central projections of population are close to the lower bound of the set used in the first Assessment. Long term economic growth is now expected to be around 1.5 per cent per year13, down from a very stable historic average of around 2 per cent.14 Infrastructure policy must be designed to work across the full range of reasonably plausible future scenarios if it is to remain relevant in the long term.

Models of long term changes in the climate predict higher temperatures on average and more intense rainfall than previously, but also a wider range around the central case,15 showing that better information can reveal more uncertainties than were previously known. This underlines the importance of keeping options meaningfully open.

Technological change is particularly difficult to predict and can have a profound impact on infrastructure. Technology can change the need for a particular piece of infrastructure or lower the costs of operating it. And it can do the same for entire systems of infrastructure. Some technological changes are sufficiently near market and well understood that they can be reflected in scenarios, whilst others are not. Some technologies make behaviour change much easier when triggered by another event like the pandemic.16 Steam as a technology preceded steam trains by around a hundred years but steam trains, when they did arrive, had a significant impact on where people chose to live in the 19th century.17 Such high impact disruptors could take demand for infrastructure, or its costs, well outside the range of reasonably plausible scenarios. But what these technologies are and when they will have their greatest impact is near impossible to predict. Including hedging, or “preparedness” activities, alongside more standard infrastructure policy, can reduce the costs of adjusting to a radically different future.

Government policy that apparently has little to do with infrastructure can affect where and how much infrastructure is required. For example, the government’s skills policy18 has led to an expansion of the student population from two hundred thousand in 196019 to 2.7 million today,20 affecting population growth in university towns and the country’s industrial mix, changing both the scale and nature of infrastructure required in the UK. The impact of government policy outside of the infrastructure space is important context for the Commission to understand without seeking to influence. Remaining vigilant to this kind of change is an important part of ensuring the full set of possible futures is considered.

Next steps

As the Commission develops the second Assessment, it will produce scenarios of the future that reflect the wide range of uncertainty in the literature around infrastructure demand and cost. It will ensure a basic level of consistency between the range of scenarios in each sector, without introducing undue complexity.

The Commission will consider how to apply ideas about designing for multiple alternative futures, keeping options open, adaptive frameworks, and procedures that improve preparedness.

The rest of this paper describes in more depth the approach the Commission has developed to managing uncertainty, the review of energy and transport scenarios and the updated analysis of infrastructure drivers.

Next Section: Introduction

The Commission’s role is to provide impartial, expert advice on major long term infrastructure challenges. Infrastructure often has a long life, with the expectation that it will continue to provide services far into the future, but the nature of the future that infrastructure will inhabit is far from certain.

Introduction

The Commission’s role is to provide impartial, expert advice on major long term infrastructure challenges. Infrastructure often has a long life, with the expectation that it will continue to provide services far into the future, but the nature of the future that infrastructure will inhabit is far from certain.

The Covid-19 pandemic has demonstrated the critical importance of planning for unpredictable events and has sparked a renewed interest in managing uncertainty among infrastructure policy makers. Now more than ever it is clear that good decision making should account for uncertainties and minimise vulnerability to the unexpected.

This paper sets out an approach that the Commission believes could substantially improve the way infrastructure policy responds to and manages uncertainty about the future. The second Assessment presents an opportunity to take a significant step in developing infrastructure policy that is robust to uncertainty .

The Covid-19 pandemic has spurred a resurgence of interest in the topic of uncertainty, highlighting the particular set of challenges faced by infrastructure. The pandemic was a dramatic example of a shock that radiated through all dimensions of society and the economy. The possibility that a pandemic could cause massive disruption had already been recognised but was more widely expected to be a flu. Covid-19 is a reminder that the future often does not materialize as expected.

Infrastructure policy routinely faces three challenges in relation to managing uncertainty: overconfidence in forecasts of the future; failing to design policy in response to uncertainty; and inaction in the face of uncertainty, in some cases leading to under investment and in others to decisions based on convictions rather than evidence.

Examples of over confidence in forecasts are common both in the UK and internationally. Ciudad Real International Airport in Spain opened in 2009 with capacity for around 2 million passengers per year, but closed three years later after all airlines withdrew all routes to the airport. Forecasts of passenger numbers had failed to consider competition from other better connected airports and the effect of the financial crisis on demand for air travel in Spain.21

Even when good analysis of uncertainty exists, it can struggle to gain traction in the design and decision making processes that most require it. This may result from lack of time and resources to devote to the issue.22,23 It may be that the governance framework encourages a particular attitude to future risks, or a project’s own inertia – the race to build – gets in the way of considering uncertainty about the future (whether that’s driven by political, stakeholder, institutional or delivery factors).

The LSE Growth Commission and the Armitt Review that proposed a National Infrastructure Commission highlighted a pattern of stop start planning and long term underinvestment in infrastructure.24 The tendency to choose to change nothing in the face of uncertainty, called status quo bias, can partially explain this. Status Quo bias acts as a powerful force to retard investment and can become institutionalised in a focus on the risk of stranded assets, ignoring the risk of failing to deliver much needed services. ‘Conviction narratives’, where a project is based on belief rather than evidence of need, can look like an attractive antidote to status quo bias.25 But conviction narratives create significant delivery risks for major infrastructure when evidence emerges to contradict them and can lead to the pattern of start stop projects the Commission was set up to avoid. Instead, there are more systematic ways to navigate an uncertain future.

Infrastructure delivery has almost uniquely long lead times, for assets that in some cases will last more than a century. Uncertainty in the costs of, or the future need for, infrastructure is nothing new, and forecasting the future has been a part of infrastructure planning for decades. But for sectors like public transport, the impact of the pandemic means it is not even clear from what level to begin forecasting the future.26

The Commission is exploring an action-oriented approach to dealing with uncertainty in the second Assessment, with less emphasis on prediction and more on policy design. Core concepts include flexibility, taking well-judged risks, and effective hedging against alternative futures. The aim is to build confidence in a shared view of future possibilities by developing a set of simple scenarios that are honest about their limitations and, collectively, describe the extent of conceivable and plausible future uncertainties.

The Commission has developed a toolkit of approaches to design policy and take decisions that better reflect this uncertainty. This includes using a portfolio perspective, adaptive frameworks and hedging strategies, where each are relevant, to overcome the challenges for infrastructure policy presented by status quo bias and conviction narratives. In the second Assessment, the Commission will explore whether and how these ideas can be implemented in recommendations for future infrastructure policy.

Section 2 of this paper provides more detail on this approach with examples from the Commission’s past work and other organisations. Section 3 then follows the first step in the approach, presenting analysis of the range of published scenarios for energy and transport demand, and updating the Commission’s view on a selection of key drivers behind these scenarios.

Key concepts in this paper

Scenario

A description of possible actions or events in the future.27 In this paper, scenarios are quantitative descriptions of a specific variable like demand. Scenarios express what the variable could look like given a set of clearly defined conditions and assumptions. Scenarios reflect how the context around the variable could affect its path into the future. Scenarios explicitly include the effects that confirmed infrastructure policy might have on the variable, but ignore the effects of future changes to infrastructure policy.

Policy pathway

Policy pathways are typically based on scenarios but differ crucially by including the impact of potential new policies on the variable of interest. Policy pathways describe the set and sequence of policy interventions required to meet a stated goal. A degree of judgement is often required in identifying policies that are assumed to be committed and included in scenarios, compared to policies that are “new” and represent part of the pathway.

The balance of a portfolio

A portfolio includes a number of infrastructure projects or policies. The balance of a portfolio is defined by the different characteristics of those projects or policies. In particular, in this paper balance typically refers to the mix of low-risk low-reward and high-risk high-reward projects or policies. Where risk is undefined because the probabilities of different future events are unknown, balance refers to the mix of robust investments, strategic bets and hedges (defined below).

Robust investment

A robust investment mirrors the concept of a low-risk low-reward investment, in an uncertain future. Robust investments perform acceptably well across a wide range of future scenarios.

Strategic bet

A strategic bet mirrors the concept of a high-risk high reward investment, in an uncertain future. Strategic bets perform exceptionally well in a small number of scenarios and so may not pay off. If they do, the pay-off is very significant.

Hedge

A hedge is like an insurance policy. It is designed to pay off in scenarios where other investments, projects or policies would perform poorly. In so doing, the hedge provides some reassurance that no matter what the future holds, economic infrastructure can continue to provide some valuable services or at the very least can adjust quickly to an unexpected set of circumstances.

Adaptive frameworks

A number of types of adaptive framework have been proposed, all aiming to help manage uncertainty about the future by adapting as that future emerges.28 For instance, “Adaptive policymaking” has three elements to it: a core of actions that have some urgency to them; other actions that seek to shape how the future looks; and others still that are designed to keep options open.29 “Adaptive Policy Pathways” attempt to identify a number of different sequences of actions that could be taken depending on how the future turns out.30

Stable core

Within an adaptive framework, the stable core represents a set of investments, projects or policies that have a firm commitment to deliver. A stable core should perform acceptably well across a wide range of scenarios to minimise the chance that it is re-opened. It may well include a range of investments, projects or policies which individually are robust investments, strategic bets or hedges (see above), and so is likely to share many characteristics with a balanced portfolio.

Adaptive pathways

Where a policy pathway might include a specific sequence of policies or actions, adaptive pathways add a series of decision points or external triggers that could see a policy maker switch from following one pathway to another.

Next Section: Understanding and managing uncertainty

To effectively manage uncertainty, it is important to first understand how uncertain the future is. Once this is understood, policy can be developed to respond to the level of future uncertainty. This chapter outlines this approach and presents policy frameworks that can encourage action in the face of uncertainty.

Understanding and managing uncertainty

To effectively manage uncertainty, it is important to first understand how uncertain the future is. Once this is understood, policy can be developed to respond to the level of future uncertainty. This chapter outlines this approach and presents policy frameworks that can encourage action in the face of uncertainty.

2.1 Building understanding of future scenarios

A thorough explanation of future possibilities using whatever evidence is currently at a decision makers’ disposal is essential for efficient infrastructure planning and delivery, including how uncertain the future could be. Psychological studies show that it can be difficult to develop an objective view of uncertainty. Developing a wide range of fairly simple scenarios is important to help decision-makers manage these challenges. The future can turn out radically different from even the widest range of scenarios, so it is good practice to stress-test policies to conditions beyond the limits of these scenarios.

2.1.1 Overconfident estimates should be corrected for

It is common practice to apply a correction for optimism bias to cost estimates. The Commission took this approach in the first Assessment. But biased estimates can come in other forms too. For instance, the National Audit Office has highlighted that major infrastructure projects can also take longer than planned and not deliver the intended aims, as well as overrunning on cost.31

Building an understanding of what the future could look like must start with a focus on how the wider context around infrastructure policy might change, and the impact this would have on costs, schedule and benefits. An obvious first step is to ensure that known biases in estimates of cost, schedule and benefits are corrected. Recent work by Oxford Global Projects for the Department for Transport (see Box 1) shows such biases can be significant but are also straightforward to correct for.

Box 1: Department for Transport with Oxford Global Projects

The report Updating the evidence behind the optimism bias uplifts for transport appraisals (2021) has gathered data from thousands of transport projects from across the world, showing both estimates and outturn values of cost, schedule and benefits.

It finds that in the UK, across over 200 road projects, costs in “final business cases” are underestimated by 20 per cent on average and benefits are overestimated by one percent on average. Fewer than 20 rail projects were examined and, in this small sample, costs were underestimated by 39 per cent on average whilst benefits were overestimated by 10 per cent. Rail also suffered from schedule overruns of nine per cent on average whilst roads were delivered two per cent early on average.

Perhaps more significantly for the Commission’s work, the study finds that in the earliest stages of project development (when the Commission is typically involved), people tend to be particularly over-optimistic in relation to lower probability events that could affect costs. This suggests that uncertainty may be treated least well when it is at its highest level. The report recommends that at the earliest stage in a project’s life, its ‘strategic outline business case’, expected costs should be increased by 56 per cent for a rail scheme and 46 per cent for a road scheme.

[Box reference32]

2.1.2 A wider range of simpler scenarios

In the context of this paper, ‘scenarios’ are used to describe the possible future context within which infrastructure policy should be made. This is distinct from ‘policy pathways’, which capture the effects of new infrastructure policy towards a specific goal.

There are innumerable events that could affect what the future looks like. Whilst the large majority have some historical precedent, it is rarely possible to predict the likelihood of them occurring in future. Instead, it is increasingly common in infrastructure planning to set out a range of possible future scenarios, without a view on how likely each might be.

To prepare for the second Assessment, the Commission has undertaken a literature review of scenarios produced by other organisations, discussed further in section 6, which included everything from straight line extrapolations of past trends, to highly complex optimisation based models with many hundreds of parameters.

In general, considering a wider range of simpler scenarios has significant advantages in comparison to complex modelling of only a few. Scenarios based on a small number of key assumptions make it easier to spot their weaknesses and leave more time and resource available to develop alternative scenarios that do not suffer from the same weaknesses. Complex modelling is more suitable to help answer questions about the effectiveness of particular policy interventions.

There is a growing body of research that suggests simpler ‘heuristics’, or rules of thumb, can systematically perform better than very complex analysis.33 This research typically distinguishes between bias and measurement error. Bias occurs when information is available but interpreted incorrectly or ignored entirely.34 Simple models suffer from bias because they exclude many details captured in more complex models Error occurs because samples of data inevitably vary in some way from the true data they seek to represent and the underlying relationships between variables may not be fully understood.35 Complex models suffer from greater errors, particularly when there is high uncertainty, as they include more sources of possible error and less well understood relationships. Measurement error, or errors in the choice of modelling assumptions, can compound rapidly in complex models and provide misleading conclusions, whereas carefully chosen simplifications can perform better. Where uncertainty is high, the errors introduced by complex modelling can outweigh the biases that are eliminated by trying to take account of more factors.

Away from infrastructure investments, heuristics are common and in particular help to improve outcomes in clinical settings where decisions must be taken fast and in the face of uncertainty about a patient’s true condition. Using real data from a hospital in Michigan USA, researchers have looked at the performance of three strategies for deciding how to treat suspected heart attacks and found that a set of three simple sifting rules systematically out performed both doctors’ judgement and complex statistical analysis.36 The sifting rules struck an effective balance between the biases in doctors’ judgement (that tended to over treat patients), and measurement error in the statistical analysis (that tended to under treat patients).

With each scenario driven by a simpler set of interactions, it becomes more important to ensure the set of scenarios spans a wide range of uncertainties about the future. Again, there is a balance to strike between reflecting such a wide range of scenarios as to demonstrate that anything could happen, which fails to lead to any useful action, and choosing scenarios that span such a narrow range that they are essentially just variations on a central projection. It is not helpful to create hard and fast rules about how wide a range of scenarios is wide enough. An alternative might involve a process of challenging the range described by scenarios and exploring what would need to be believed to justify widening the range.

The Commission will explore a relatively simple approach to developing and challenging a wide range of scenarios for the second Assessment, drawing both on consensus views from the literature and its own assessment of the key drivers of change in each sector.

2.1.3 Challenging assumed stability

It is important to identify what is not expected to change for a number of reasons. On the one hand, this helps to provide some certainty for the purposes of planning and policy design. In particular it may help to identify ‘core’ investments or recommendations that are worthwhile under any scenario. But it also creates an opportunity to challenge assumptions about what is not expected to change and, in so doing, identify unusual events that might occur more often than we first think.

It is tempting to believe something is unlikely to happen in the future simply because it has never happened before. A ‘black swan’ was a metaphor for an impossible event until Dutch explorers landed in western Australia in 1697, where black swans are common.37 Even reasonably foreseeable events, like financial crises or ash clouds associated with volcanic activity, are often ignored until they actually happen. When significant risks are identified, like a global pandemic, it is not unusual to fail to effectively plan for them.

Identifying events or conditions that would cause a project to perform optimally and conversely to fail entirely can be a simple extension of the role of a ‘red team’. A red team subjects policy proposals to rigorous analysis and challenge,38 by asking what must one believe about the future for this policy to excel and to fail, and how likely are each of those futures to occur?

Such thought experiments can appear esoteric, but are essential precursors to the more practical question, what are the actions now that will set this policy up to seize opportunities and minimise losses outside the already wide range of scenarios?

The next section describes how infrastructure policy can be designed to reflect a confident understanding of future uncertainty.

2.2 Reflecting uncertainty in policy design and decisions

It is not enough simply to understand what the future could look like. If infrastructure policy is to stand the test of time it must be designed to respond to that uncertainty. This should involve designing policy that performs well in multiple scenarios, highlighting scenarios in which the policy performs less well, and ensuring it complements others’ policies that collectively serve the country’s need for infrastructure no matter what the future holds.

2.2.1 Recommendations should be robust to the widest range of scenarios

When designing policy to deliver positive impacts in an uncertain world, it is important to explore how multiple scenarios may influence the policy’s performance. There is no hard and fast rule about how many scenarios a recommendation should perform well in, and in some specific cases the answer may be just one, but in general a more future proof policy will deliver benefits across a larger number of scenarios. If a policy is to be considered robust to uncertainty it should perform acceptably well across a wide range of possible futures.

Terms like ‘central projection’ and ‘most likely scenario’ are commonly understood to mean that other scenarios are much less likely to occur, but that is rarely the case. Scenarios are typically developed because there is insufficient evidence to ascribe probabilities to any particular future, and in that context the middle scenario in a set of, say, five may be no more likely than any others: there might be a 20 per cent chance the future looks similar to that middle scenario (or more or less), and an 80 per cent chance it does not. Though it may be technically and economically attractive to optimise policies for a particular version of the future, policies that are designed for one particular view of the future will be less effective if the world turns out differently. It may be necessary to sacrifice some expected performance in the central projection to achieve acceptable performance over a wider range of possible futures. Furthermore, national infrastructure takes time to plan and build, so whichever future is most likely now may not be the most likely future when plans have been implemented.

There are a number of strategies to help design policy that is robust to a range of scenarios. Two popular approaches involve designing for one scenario and stress testing it to improve performance under others or running separate policy design exercises that target different scenarios, and then looking for the commonalities.

Planning for one and modifying to fit other scenarios is appropriate when the downsides of being wrong about the choice of scenario are minimal. It is simple to implement in a project environment, with clear assumptions and risk registers leading to specific mitigation plans.

Planning for multiple scenarios can be appropriate when the downsides of being wrong in any scenario are significant, and decision makers are looking to identify activities that perform acceptably across many scenarios while waiting for more clarity over which scenario will ultimately unfold. It can involve competing teams working on each scenario, setting up ‘red teams’ to challenge assumptions, or categorising proposals from stakeholders and others according to the scenarios in which they would perform best.

Box 2: Planning for multiple scenarios

Engineered Greenhouse Gas Removals (2021)39

The Commission explicitly looked at a range of scenarios for which others (the Climate Change Committee, UK government, Royal Society, Energy Systems Catapult, National Grid ESO and University College London) had mapped out pathways towards the net zero target, and established that engineered greenhouse gas removals are required in most of these scenarios. There is a case for investing in them in spite of remaining uncertainty over how much of this technology will be required.

Rail Needs Assessment for the Midlands and the North (2020)40

The Commission identified a core portfolio of rail investments that were likely to be deliverable and beneficial across a range of scenarios. It also discussed conditions which, if satisfied in the future, would support further investments on specific routes.

2.2.2 Transparency about the risks of being wrong

It will not be possible to design every policy to perform well in all scenarios. It is important to consider the consequences of designing for scenarios that ultimately do not come true. To do this effectively, a mix of quantitative analysis and careful judgement is likely to be required.

Quantitative analysis can help to identify in which scenarios a policy might perform poorly, with judgement required over whether this represents a risk worth taking.41 Infrastructure policy is rarely low risk, but it is often possible to identify when the costs of being wrong are lower with one course of action than another. Box 3 provides two examples from the first Assessment of how two judgements on the risks of being wrong led to quite different policy recommendations by highlighting ready alternatives available in one case, and none in the other.

This perspective is sometimes formalised in quantitative approaches such as ‘regret analysis’ or Wald’s ‘maximin analysis’, and has featured in decision making frameworks for infrastructure investment in the UK and elsewhere.42 Such approaches have been critiqued for leading to overly conservative investment decisions.43 Used appropriately, and in particular with a more qualitative judgement-based element, it is helpful to consider the risks of being wrong alongside other perspectives. The next section discusses approaches that are designed to counter any systematic tendency to risk aversion, by viewing individual policies within the context of a wider portfolio of investments, and by adapting to the future as it unfolds.

Box 3: Quantitative analysis with qualitative judgement

Investing in water assets

To generate recommendations for the water sector in the first Assessment, the Commission looked at the major determinants of demand over the long run, the useful life of water assets, the need to restore sustainable quantities of water in the environment, and the risks of being wrong. It judged the risks of being wrong about asset life to be very low (the materials are well understood, there are no real alternatives to underground pipes, and it is hard to imagine conditions underground across the whole country changing significantly over the life of the assets). The need to reduce water withdrawals in sensitive environments that have been overexploited was already recognised by government and policies were in place to enforce sustainable abstractions. The risks of being wrong about demand are higher, but population forecasts at the time were all pointing to some level of increase. If more water infrastructure is built than is needed in the short run, population growth will still increase demand to match capacity in the longer run, and well within the useful life of the asset. The cost of being wrong is very low.

Investing in nuclear assets

Nuclear assets are also relatively long lived and demand for energy can be expected to grow with population over the long run. But the Commission recommended a one plant at a time strategy instead of a full scale early roll out. It judged that there was a significant risk of locking the UK into a high cost technology for a very long time when there are clear alternatives available. The fixed costs of investment and the need for regular maintenance to retain the integrity of the assets meant temporarily closing a nuclear plant once built is not a viable option. The costs of being wrong about the need for nuclear are much higher than for water and justify a one plant at a time approach.

2.3 Evidence based approaches to action in the face of uncertainty

There is no single approach to policy design that will work for all policies in all circumstances. This section explores two specific approaches that could support action oriented and evidence based decisions to invest in infrastructure in the face of uncertainty.

Building, maintaining and operating infrastructure can be risky, and there will be times where bold and decisive action is needed to deliver future infrastructure. It is right for investors including government to consider high risk, high reward actions as part of a wider balanced portfolio. In other circumstances, uncertainties can be expected to resolve themselves over time. In the context of consistent long term policy goals, and with clarity over the triggers for considering new information, adaptive strategies can be more appropriate than one off decisions.

2.3.1 A portfolio perspective can help to balance risks and uncertainties

To justify infrastructure policies that may be individually risky, it is critical to understand whether each policy might enhance a wider portfolio’s performance. There are two key aspects to this: seeking a balance of investments or policy recommendations across the portfolio, and ensuring these different investments face different risks.

There is a place for high risk infrastructure projects where those risks are understood and effectively managed within a wider portfolio. A diverse portfolio of projects will deliver better value for money than a more uniform one. A central tenet of this approach is that projects must be in different risk classes: projects should be lower risk and lower reward or higher risk and higher reward. A riskier project needs to have particularly high returns for this effect to work. There is no place for high risk, low reward projects.

In the context of managing uncertainty, the concept of risk can be challenging because it implies an understanding of how likely an event is to occur. Scenarios do not have likelihoods attached to them. A related but different perspective on balancing uncertainties is therefore to look at whether a policy performs well across a large or small number of scenarios. Performance across a large number of scenarios need not mean it is low risk (there could still be significant risks to affordability or deliverability, and there may be some understanding of the relatively likelihood of different scenarios, even if this cannot be quantified) but might justify the label ‘robust investment’: it performs well across a wide range of scenarios. Policy that performs exceptionally well in a small number of scenarios or under very particular conditions might be considered a ‘strategic bet’. And policy that is designed to perform well when others do not might be called a ‘hedging strategy’.

Robust investments could include projects, or stages within projects, which deliver similar levels of net benefit across most alternative scenarios. In identifying these robust investments, it is important to look at the risks and uncertainties around that assessment of net benefit. For instance, it may be inappropriate to include a project that has immature cost estimates, because the methods used will mask whether the project is in fact high risk.

Major road schemes costing between £10m and £500m have shown themselves to deliver relatively stable, but by no means transformational, benefit cost ratios. Post opening evaluation studies over a 10 year period to 2012, and appraisal data for schemes since that date, both show a weighted average benefit cost ratio of around 2.7 to 1. Provided there are no significant changes in the way people use roads, this historic experience provides a good level of confidence that road schemes on this scale will continue to deliver benefits in future and represent lower risk investments with modest rewards.

With a strategic bet, there should be good evidence that: significant benefits could be delivered by the infrastructure under fairly well understood conditions; the investment is part of a strategy that aims to deliver these conditions; and there is limited scope to reduce the risks of the policy with further work. It is demonstrably ‘high risk, high reward’ and has been developed enough to take a firm decision on whether it should go ahead. For instance, actions might be required by other parties to deliver the housing benefits associated with a new railway station, and whilst there is good reason to think those parties will do their best to build the houses, it is outside the control of the infrastructure authority to ensure they do so. This is critically different from a blind bet, where there is insufficient evidence of the conditions required for the infrastructure to deliver high rewards.

The first Assessment recommended a national full fibre connectivity plan. There were clear scenarios in which this recommendation would deliver significant benefits in the order of tens of billions of pounds, but also others in which it would not. Big improvements in alternative technology, or simply low take up rates of full fibre by households, could make fibre to the premises unnecessary. At the time of the first Assessment, when there was less evidence from other countries, this recommendation fulfilled the criteria of a high risk and high reward strategic bet.

Hedging activities should pay off in scenarios or situations where the stable core, or perhaps more significantly where a strategic bet, does not. A well designed portfolio will have a stable core that performs well across almost all scenarios. In this case hedging activities may target futures that are well outside the range of reasonably plausible scenarios. Events that take the future outside the range of reasonably plausible scenarios are likely to be rare, but very significant when they do occur. As a result, hedging activities may be focused on preparing to respond to unlikely events, and in a minority of cases may involve complementary investments that would perform well when others do not.

The Commission has previously recommended a one at a time approach to new nuclear capacity, to maintain the knowledge and the supply chain to build nuclear power plants just in case a renewables dominated power network proves unworkable. This hedge against the risk of renewables failing is not without cost, but the cost is worthwhile given the high value of a reliable electricity supply.

It can be challenging to define what is meant by a good balance of risks and uncertainties across the portfolio. It is not for the Commission to say what risk appetite government should have, but the Commission does occasionally make the case for a different balance of risks where it sees the potential for greater benefit. A purely low risk portfolio is clearly suboptimal, as is one with a very large proportion invested in high risk projects. Whilst there is no right answer to what is a good balance of risk, by looking at how risky a portfolio is, it is often possible to identify ways to improve that balance of risk. The Commission has the capacity to do this by looking across the entire range of infrastructure investments.

2.3.2 Adaptive frameworks can build confidence in delivery

There are strong political and economic incentives for government to specify all the details of an infrastructure project at an early stage.44 Political capital can be gained from grand promises, which create delivery momentum and focus teams on the solution they are building. But not all decisions need to be made at such an early stage and within a context of consistent long term policy goals, keeping options open can materially improve the chances of delivering benefits as the future becomes clearer. At the moment that these decisions must be made, plans should be adapted to reflect the best available information.

There are typically costs associated with keeping options open, but the costs of locking into the wrong project or the wrong approach too early may be much higher. Economic infrastructure can deliver services for many decades, so mistakes and missed opportunities can endure for many years. Equally, concern for avoiding mistakes can lead to inaction and status quo bias, ignoring the costs of this inaction.

Adaptive frameworks involve a firm commitment to elements of a project or policy that are more likely to deliver some benefit (whether to customers or to the delivery authority in the form of insight), providing a lower risk opportunity to learn what works and develop benchmarks for the potential costs, timeframes and returns of subsequent phases of investment.

There are clear trade-offs between keeping options open and providing adequate time for delivery planning, so it is critical to have a strong understanding of the design, planning and consenting timescales, and the scope within those for leaving options open. In some instances, it will be possible to design infrastructure to make it easier to enhance at a later date. For example, laying pipes beneath road verges as part of routine upgrades, ready for the fibre optic and power cables likely to be needed for connected vehicles.

Timing is a hugely important factor in being ready to adapt to changes in the future. The planning stages of a large, risky project are rarely short, and provide an opportunity to look for indications that the conditions are right to fully commit to such a project. Setting out specific ‘triggers’ for changing the scope of a project can sometimes help, though the triggers should be chosen with care. For instance, the pathway of global emissions changes relatively slowly, so decision-makers will know well in advance whether they need to start building for a world that is not 1.5 degrees warmer, but 3 degrees or even more.

Adaptive frameworks do not involve building half a bridge. That is, the initial commitment should yield insights directly, allowing the infrastructure authority to learn from its experience of costs, benefits and schedule risks before committing to future stages of work. In some cases, this may still involve upfront commitments to large projects over many years. In others, the benefits might come from finding out a first phase delivered unneeded infrastructure, and further investment should be avoided or at least delayed. Adaptive frameworks may generate stranded assets, but on a smaller scale to all or nothing investment decisions: they keep options open that can be affordably written off if necessary. Hedging or preparedness strategies should be considered alongside adaptive planning.

Box 4: High Speed Rail in France

The experience of high speed rail in France45 can be viewed as a successful adaptive approach to infrastructure planning. The first line between Paris and Lyon was approved in 1978, and opened by then President François Mitterrand in 1981. Knowing such lines could be built affordably, rapidly and with stakeholder support, Mitterrand used the opening ceremony to announce his approval of a second line from Paris towards the West Coast. This second line opened in full in 1990.

With proof of ongoing demand for high speed rail services, in 1991 the government committed to a national masterplan for high speed rail links. This has subsequently seen three new lines and two significant extensions added to the high speed rail network in France.

Stakeholder engagement for Tours-Bordeaux section46

The Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) points to France as having an effective consultation process for major transport infrastructure. Public meetings to inform local residents were part of the process even at the earliest stages, and over the course of the project nearly 20,000 interested members of the public visited construction sites to understand what was going on. Consultations lead to meaningful changes to plans: the route was modified, local roads improved, and natural habitats created in compensation for others disturbed or destroyed.

Adaptive frameworks face a particular challenge in staying adaptive beyond the earliest stages, as delivery and political momentum for one particular solution builds. Skilful communication and stakeholder management is critical to convey the degree to which there is (or should be) a commitment to explore, or to actually build, a new piece of infrastructure.

Effective communication around adaptive pathways is emerging as a key part of long term water resource management strategies in England. For instance, Water Resources South East (WRSE) consulted in January 2022 on their approach to adaptive planning to future-proof water supplies in the South East. The approach involves a specific set of potential schemes to deliver in the period 2025-2040, three alternative pathways for the period 2040-2060 and further alternative pathways thereafter.47 The consultation document has a substantial section on how WRSE is planning for an uncertain future and cites feedback from customers that they ‘would prefer a plan that has the flexibility to deal with future changes.’48

The Commission has worked with the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development on this issue and recommends seeking broad based support for infrastructure plans as a way to reduce uncertainty around funding and approvals. The paper Developing Strategic Approaches to Infrastructure Planning discusses the issue in more depth.49

Where uncertainty about the future means the right type and scale of infrastructure is unclear, it is all the more important to develop broad-based support for action that leaves room to adapt.

Next Section: 3. Review of scenarios and their drivers of change

This section presents the Commission’s review of scenarios in the energy and transport sectors and goes on to discuss how key drivers of infrastructure demand and supply have changed since the first National Infrastructure Assessment. It supports the case for the approach described in section 3.

3. Review of scenarios and their drivers of change

This section presents the Commission’s review of scenarios in the energy and transport sectors and goes on to discuss how key drivers of infrastructure demand and supply have changed since the first National Infrastructure Assessment. It supports the case for the approach described in section 3.

3.1 Scenarios

Scenarios describe the possible future context within which infrastructure policy should be made. This is distinct from ‘policy pathways’ towards a specified policy goal, which would capture the effects of new infrastructure policy.

The Commission has looked at work published by other organisations to understand the full range of demand scenarios relevant to its sectors and will seek to reflect this range in its own analysis for the second Assessment. The published literature on energy and transport demand scenarios provide helpful illustrations of the degree of uncertainty faced by infrastructure policy makers. Scenarios for these two sectors are routinely published by industry, government or academia. They are often based on large and complex models and represent fairly wide but reasonably plausible ranges.

In reflecting the ranges produced by other organisations, the Commission does not need to accept every input assumption used to generate them. Any given level of demand can be achieved by many different combinations of input assumptions. Describing the full range of possible future scenarios for demand and cost is far more important than the precise combination of inputs that generated each scenario.

All the Commission’s recommendations will be consistent with net zero. In some cases, that suggests looking only at net zero scenarios, but recommendations may also consider what more would need to be done in scenarios that do not achieve net zero, in effect describing a policy pathway from the scenario back to the net zero target. A number of publications include demand scenarios that lie outside the range of net zero consistent scenarios.

3.1.1 Review of energy scenarios

The energy literature is dominated by the government’s net zero target, which acts as a constraint across many but by no means all the published scenarios. With electrification expected to play a significant role in transitioning the economy to net zero carbon by 2050, scenarios of electricity demand provide a good insight into the wider sector.

Electricity demand in 2020 reached a thirty year low of 330 TWh.50 Demand has been declining for a number of years,51 with a larger than expected fall in 2020 primarily due to responses to the Covid-19 pandemic.52 Scenarios of future electricity demand start from slightly different levels in 2020, depending on when they were produced, but all are broadly consistent with observed demand in that year.

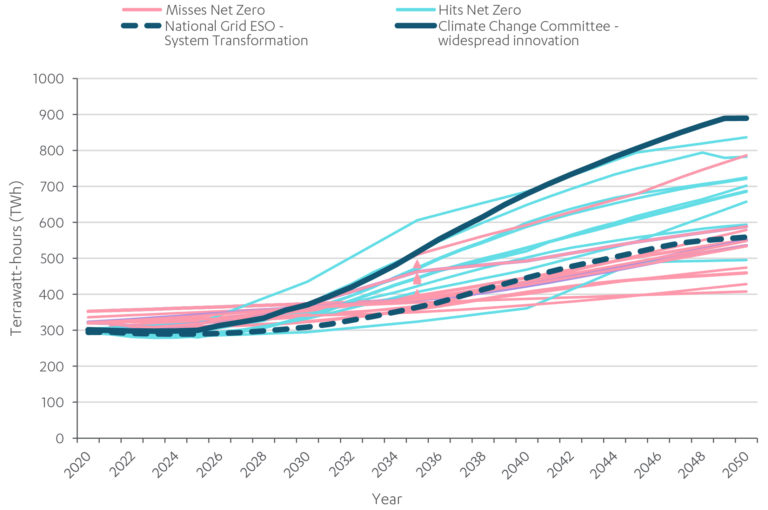

In total, the Commission has identified over 30 different scenarios for electricity demand published by eight organisations. There is broad agreement across these scenarios that the 2020s are likely to be characterised by only modest changes to total demand for electricity. All scenarios show an increase in demand for electricity in the period from 2030 to 2050, as significant sectors of the economy switch to electricity and away from fossil fuels.

In a net zero 2050, the published literature shows demand for electricity could be in the range of 560-890 TWh. This would represent an increase compared to 2020 of between 70 per cent and 170 per cent. For context, the 30 years from 1970 to 1999 saw around a 68 per cent rise in electricity consumption,53 while the 1950s and 1960s saw much faster growth but from a lower base.54 The change to the sector is not unprecedented, but is significant even at the lower end of the scenarios.

Figure 3.1: Demand for electricity in 2050 could be between 560 and 890 TWh

Scenarios of future electricity demand in the UK

Source: See appendix 1 for full list of scenarios in this chart

Many of the higher scenarios assume there is significant electrification of heating and that nearly all road transport including HGVs is electrified, which adds substantially to overall demand. Some also include electricity demand for direct air carbon capture and storage. But it is possible to imagine somewhat higher electricity demand associated with less progress on energy efficiency. This further reinforces the need to ensure policy which is designed for the full range of scenarios is also tested against events that could take the future outside this range.

Some lower demand scenarios foresee a major role for hydrogen in heating and little change to consumer behaviour. Again, it is possible to imagine lower electricity demand if for instance efficiency gains are substantially higher than assumed.

3.1.2 Review of transport scenarios

The transport literature is markedly less diverse than energy, with most scenarios closely related to those produced by the Department for Transport. This is unsurprising given that both road and railway infrastructure investment is funded to some extent by government, creating a strong incentive to use scenarios the government recognises. However, this apparent convergence in scenarios should not be taken as meaning that the uncertainty is low. The cluster of current scenarios that are close to Department for Transport projections may not be sufficiently broad to reflect all future uncertainties. The impact of the Covid 19 pandemic on mobility illustrates the possibility for surprising shifts from previous demand trends.

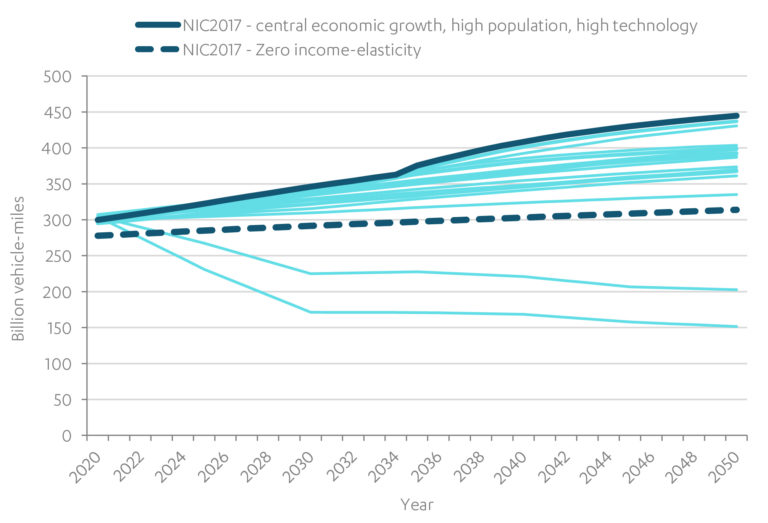

Roads are used for around 90 per cent of the miles travelled by passengers in Great Britain55 and 79 per cent of all freight miles.56 Roads dominate trends in the wider transport sector, so are presented here to illustrate findings. Road demand by all vehicle types in England in 2020 was significantly affected by the Covid-19 pandemic,57 declining from a historic high of 307 billion vehicle miles in 2019 to some 242 billion vehicle miles. All scenarios of future road demand pre-date the pandemic, so do not reflect recent history or any potential changes to future travel behaviours that might result. The Commission has identified 11 scenarios published by two organisations, in addition to the ten scenarios the Commission produced in 2017 for the first National Infrastructure Assessment. All seven of the Department for Transport scenarios and two of the four scenarios from the Centre for Research into Energy Demand Solutions project a relatively straight line increase in demand for road transport. The Commission’s own scenarios are similar, with a slightly wider range than those by the Department for Transport.

The final two demand projections from the Centre for Research into Energy Demand Solutions describe a radically different vision of future transport demand, with substantial declines between 2020 and 2030 to levels not seen since the early 1990s.58 In these two possible futures the authors take a view on what they would like to see change in relation to government policy and societal behaviours over the next 30 years. The Commission will use scenarios to define the starting conditions from which to begin its work in the second Assessment and needs to avoid building in assumptions about changes to infrastructure policy. Pathways like this have an important place in policy making, but not in defining the starting conditions on which to build policy.

The Commission’s own work on behaviour change and infrastructure beyond the Covid 19 pandemic suggests that any given pre-pandemic transport demand scenario could be adjusted downwards by up to 10 percentage points as a result of the pandemic.59 In effect, every scenario in Figure 1 could begin in the region of 270 billion vehicle miles rather than 300 billion vehicle miles.

Stable trends in travel behaviours since the pandemic are yet to be established, so conclusions in the Commission’s behaviour change study from May 2021 may already be outdated. The most recent data on travel demand shows that in late April and early May 2022, road vehicle use in Great Britain had reached similar levels to equivalent weekdays before the pandemic, and exceeded similar levels for weekends.60

In 2050, the published literature shows demand for road transport could be almost 450 billion vehicle miles per year. That is an increase of around 47 per cent on pre-pandemic levels, and higher than the 30 years to 2019 (40 per cent growth) but substantially lower than all other 30 year periods since 1950.61 The Commission’s own scenario ‘central economic growth, high population, high technology’ defines the upper bound of this range and is very similar to Department for Transport’s ‘Shift to Zero Emissions’ scenario.

Figure 3.2: Demand for road transport in England in 2050 could be as high as 450 billion vehicle miles, or broadly similar to today

Road demand scenarios for England, 2020 to 2050

Source: see appendix 1 for full list of scenarios in this chart

Most scenarios show steadily rising demand, albeit with some rising more slowly than others. The Commission’s own ‘zero income elasticity’ scenario imagines a world in which the historic link between economic growth and transport demand is broken. Here, future increases in transport demand are driven by population growth and technology that makes it cheaper or more attractive to drive. Combining the Commission’s more recent work on behaviour change beyond Covid 19 with this scenario might indicate a lower bound close to 300 billion vehicle miles in 2050. The Commission will further develop its view of an appropriate plausible lower bound for road transport.

The scenarios presented here for both electricity and road transport are highly aggregated national viewpoints that inevitably mask the potential for greater variation at smaller scales. Lower electricity demand might arise from reliance on hydrogen and carbon capture and storage, but low levels of demand could also be delivered with substantial electrification of the economy and significant improvements in energy efficiency. There are substantially different policy implications from these two apparently similar scenarios. Equally, at regional and local levels road demand may experience much wider variation than the national average. It is essential to interrogate scenarios and the drivers of change behind those scenarios.

3.2 Understanding drivers of change in infrastructure

Many of the underlying trends driving future demand scenarios have changed significantly in the past five years, but the manner in which they influence infrastructure remains stable. The literature review discussed above includes scenarios published between 2014 and 2022, with some evidence of systematic changes in scenarios over the period. Figure 3.1 above illustrates the point, with the set of more recent net zero consistent scenarios covering a much narrower range than older scenarios that were not constrained in this way. This may be because the choice to pursue net zero limits the set of technologies available for power generation, resulting in less uncertainty over price and therefore demand. In this context, it is important to have an up to date understanding of key drivers of change in infrastructure.

The Commission has considered six areas that impact the supply and demand of economic infrastructure: population, economic growth, environment, technology, behaviour change and government (non-infrastructure) policy. The first four of these were the subject of a series of Commission discussion papers in the run up to the first Assessment. A direct comparison can be made with previous expectations of population, economic growth and environmental change, and reinforces the need for the approach to managing uncertainty discussed in section 5.

3.2.1 The links between infrastructure and selected drivers of change

Population and demographic change have a very direct impact on demand for infrastructure services both overall and in terms of where in the country that demand is concentrated. Infrastructure assets deliver services that are consumed by households, businesses, government and the third sector. Around 70 per cent of UK output is bought by UK consumers,62 meaning population change also indirectly affects demand for infrastructure via businesses. Government and the third sector predominantly serve the UK population (with exceptions like overseas aid), so changes in population affect these sectors’ demand for infrastructure services too.

The link between population and economic infrastructure is discussed in more detail in The impact of population change and demography on future infrastructure demand63 and has not changed substantially since this was published in 2016.

Economic growth is associated with rising demand for infrastructure services. As households get richer, they tend to buy more and use more infrastructure services like water and electricity. Consumption of goods tends to generate waste and the need for waste infrastructure, while consumption of personal services and leisure opportunities typically require transport, and online services need digital infrastructure. Economic growth and demand for infrastructure services reviewed recent estimates of the relationship between economic growth and demand for infrastructure and found, in general, demand rises less than proportionately to income growth.64

The environment affects both supply and demand for infrastructure. The frequency and severity of extreme weather associated with climate change represents risks to supplying infrastructure services and requires adaptation of the infrastructure itself. Climate and environmental change can also be expected to lead to more flooding and higher demand for flood protection infrastructure. It may also reduce water availability and raise the costs of water treatment.

Meeting the demands of a net zero carbon economy by 2050 represents a significant driver of change across all economic infrastructure and constrains what the future must look like.

Technology must be analysed differently from other drivers of change. By its very nature, there is no single consistent way to directly measure the rate of technological change across an economy: every advance in technology is qualitatively different from the previous one. Rather than look for quantitative forecasts of technological change, the Commission has developed a framework for understanding its possible impact on infrastructure and a systematic review of technologies on the horizon.

Technology can act as a direct driver of infrastructure supply and demand. It can interact with other trends to enable behaviour change and may support delivery of infrastructure policies like achieving net zero carbon. There are six elements to the Commission’s technology driver framework which help to describe its effects on individual pieces of infrastructure and whole systems.

Technology can:

- Reduce the need to build new infrastructure: Innovations in how infrastructure is managed can help to use existing infrastructure more efficiently, reducing the need for new building programmes

- Create demand for additional infrastructure: The internet has provided an opportunity to move many services online, which has in turn directly increased demand for digital infrastructure to access these services

- Lower the cost of supplying infrastructure: Innovations in materials and faster or less wasteful manufacturing processes can lower the costs of supplying infrastructure

- Create demand for a new infrastructure system: Newer modes of transport have historically offered faster access to a wider range of services and opportunities, requiring big expansions in their networks to accommodate demand

- Reduce demand for infrastructure systems: New technologies like television in the 1950’s have reduced demand for competitor technologies like cinema, and in so doing may have contributed to falling demand for evening and weekend public transport services

- Create more vulnerable infrastructure systems: The success of reliable electricity infrastructure has led many previously independent infrastructure systems to become dependent on electricity. Gas boilers in the home are now typically ignited by an electrical spark instead of a pilot flame. These other infrastructure systems now share risks faced by electricity infrastructure.

Behaviour change and non-infrastructure policy represent important additions to the set of drivers and are discussed at the end of this section.

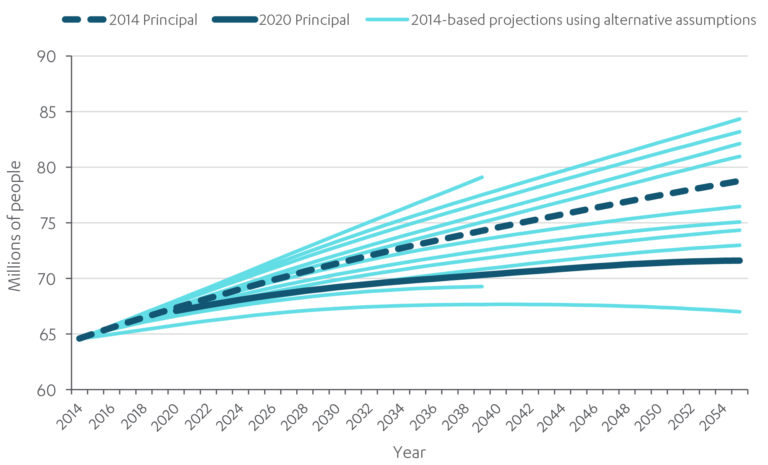

3.2.2 Population is expected to grow, but more slowly than previously

Projections of national population growth have changed significantly since 2016 (based on 2014 data) and are subject to on-going revision by the Office for National Statistics. They will be revised again in 2023 based on the 2021 census. The latest interim publication contained a single scenario – its 2020-based principal projection.65

The 2020-based principal projection shows that by 2050, the UK population may have grown to 71.4 million. That is 6 million people fewer than in the 2014-based principal projection, but within the range of all 2014-based scenarios. This significant fall is largely a result of successive incremental revisions to fertility rate and life expectancy: both these assumptions were revised downwards in 2016,66 2018,67 and 2020.68 Figure 3.3 demonstrates the importance of planning for a wide range of future scenarios, and shows the 2020-based principal projection overlayed on top of the full set of 2014-based alternatives.

Figure 3.3: The latest principal population projection is substantially lower than its 2014 equivalent, but still with the 2014 range

Principal population projections and alternatives, 2014 to 2050

Source: Office for National Statistics

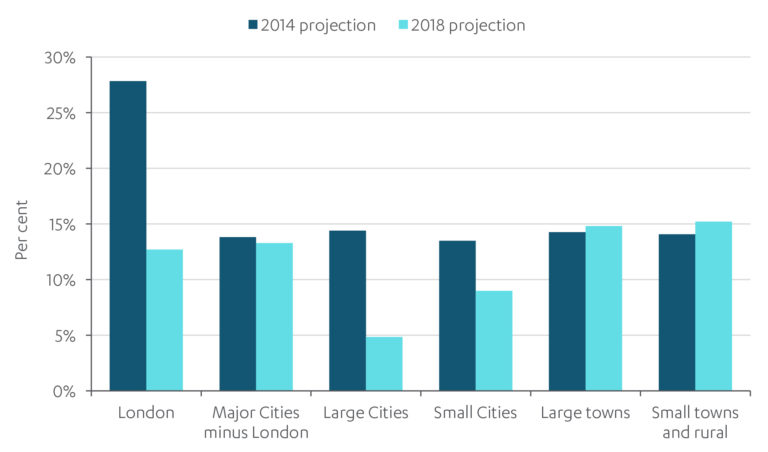

The Office for National Statistics has chosen not to publish 2020-based projections of sub-national population growth, but 2018-based data indicates that this picture has changed substantially too. In The impact of population change and demography on future infrastructure demand, the Commission found that London was expected to grow strongly over the 25 years from 2014 to 2039, with other major cities also expected to see growth ahead of the rest of the country. The 2018-based projections suggest all cities can be expected to grow much less strongly than previously thought.

The pandemic is thought to have had a very significant impact on some people’s choices over where to live and work, so the 2018-based projections are particularly open to uncertainty. The trend towards slower growing cities (in population terms) may be exacerbated, although data to verify this is not yet available.

Figure 3.4: City populations are no longer expected to be growing significantly faster than the rest of the country

Population growth projections in cities, towns and rural areas, 2014 to 2039

Source: Office for National Statistics

3.2.3 Economic growth is also expected to grow more slowly than predicted

The second half of the 20th century was characterised by annual economic growth in the range of 2-2.5 per cent, leading many forecasters at the beginning of the 21st century to believe that would continue. Since the 2007-08 financial crisis, economic growth has been far lower than this at an average of 1.2 per cent per year up to 2019.69

It has taken time to establish whether this experience is temporary or permanent, and so the Commission’s March 2017 paper Economic growth and demand for infrastructure services presented three scenarios. The central projection followed consensus at the time that growth would revert to its 20th century trend, and from 2020 to 2050 the economy would grow by 74 per cent based on assumptions from the Office for Budget Responsibility.70 Recognising this was different from the previous decade’s experience, the Commission also constructed a modest scenario with 67 per cent growth from 2020 to 2050. A final lower scenario was based on a longer-term look at growth before the 20th century and suggested only 23 per cent growth from 2020 to 2050.71

Since then, the Office for Budget Responsibility have made two significant downgrades to their expectations for long-term growth. Based on their latest March 2022 figures, the economy is expected to be 55 per cent larger in 2050 than it was in early 2020 before the pandemic began.72 That is lower than the modest growth scenario the Commission published in 2017, again demonstrating the importance of creating and then planning for multiple scenarios.

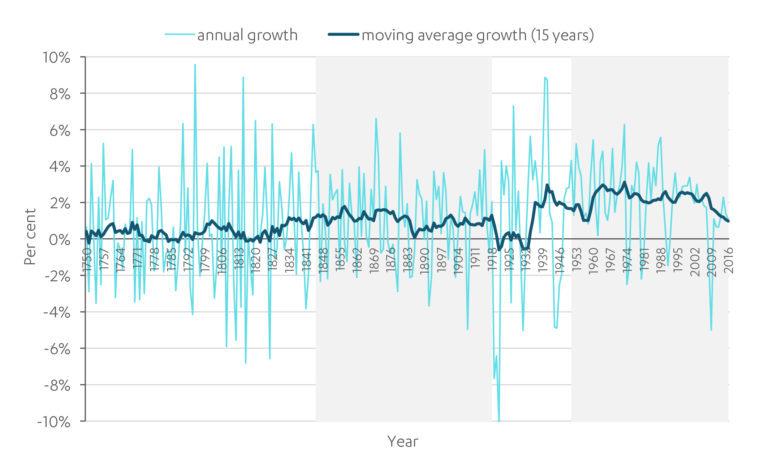

Figure 3.5 updates a chart published in Economic growth and demand for infrastructure services and illustrates the emerging step-down in long-run economic growth. It plots actual annual economic growth, overlayed with a 15-year moving average to help smooth the annual variation and identify longer-term trends. A series of step changes are visible in the smoothed line, as successive waves of technology have transformed the economy. In the most recent decade, annual growth has been consistently below the 15-year moving average, causing that smoothed series to decline in every year since the financial crisis.

Figure 3.5: There have been a number of phases of per capita GDP growth since the 1700s, and recent signs of lower growth since the 2007/08 financial crisis

Per capita GDP growth over the period 1750 to 2016

Source: Bank of England and Commission calculations

The steps between phases of growth visible in Figure 3.5 can be extremely hard to predict and are not much easier to explain with the benefit of hindsight. General purpose technologies, and their progressive adoption through the economy, may have an important role to play in explaining epochal changes in economic growth though the question of which technologies had what effect remains contested.73

The first step up visible in the figure, sometime between 1830 and 1850, can be explained by a number of alternative technologies and associated changes in society.74 The invention of steam trains and the expansion of the rail network during the 1840s and 1850s provides one possible explanation75 alongside steam ships and the electric telegraph, but by this time steam engines in some form had been in use for over one hundred years in other parts of the economy. Even once a new general purpose technology like steam has been invented, it can be extremely hard to predict when it will have its greatest impact on economic growth.76 It is equally challenging to predict when (if even) that effect may have run its course, with growth rates falling back to more modest levels.

3.2.4 Environmental change is expected, with a widening range of uncertainty

Since the Commission published The impact of the environment and climate change on future infrastructure supply and demand in 2017, a number of major new studies have been published. They demonstrate both the critical need to decarbonize the economy and to adapt to unavoidable changes in the climate, while emphasising the significant uncertainties around predicting long-term environmental change. The UK Climate Projections 2018 provides a case in point.

The 2018 projections update a similar exercise from nine years earlier, UK Climate Projections 2009 with improved modelling and forecasting methods as well as newer data on the potential impacts of a warming climate. The 2018 projections largely reinforce the findings from 2009, showing an upward trend in average temperatures across the UK, but a wide range of uncertainty around future rainfall.77 The most striking difference however is that the uncertainty range is wider in the more recent projections. Better knowledge about the potential impacts of a changing climate has led scientists to conclude the future is more uncertain than first thought and illustrates the need to remain humble about the limits to knowledge at any given moment in time. This insight reinforces the need to describe how the world must change for a policy recommendation both to perform optimally and to fail entirely.

3.2.5 Behaviour change and infrastructure

Behaviour change may be enabled by other drivers of change or may happen independently and has the potential to affect demand for infrastructure services. In Behaviour change and infrastructure beyond Covid-19, the Commission explored a range of models for behaviour change and found few historic events have afforded consumers the capability, opportunity and motivation required to trigger long lasting behaviour change. Most examples in this report saw temporary changes in behaviour, followed by a return to previous behaviours. However, the report also highlighted that the Covid 19 pandemic may be more likely to lead to a permanent shift in motivations combined with an ability to work from home, which could enable and cause long term behaviour change.78

3.2.6 The impact of non-infrastructure policy on future infrastructure supply and demand

Non-infrastructure policy has an important but indirect influence on infrastructure supply and demand. The Commission does not have a mandate to comment on non-infrastructure policy but does recognise that its work fits into a wider policy context which is important to understand.