Reducing the risk of surface water flooding

The final report of the Commission's study says action is needed to prevent more properties across England becoming at high risk of this type of flooding.

Tagged: Water & Floods

Foreword

The challenges of tackling river pollution and addressing water supply shortages have dominated public discussion about the water sector in recent months – but we risk ignoring a problem that can literally drop out of the sky at any moment.

As the climate changes, heavy rainstorms are happening more often. Sudden deluges can overwhelm drainage, leading to ‘surface water flooding’. Londoners will recall the scenes in July 2021, when parts of the city received more than twice the average monthly rainfall in just two hours; more recently parts of Leicestershire and the Isle of Wight were hit by similar incidents.

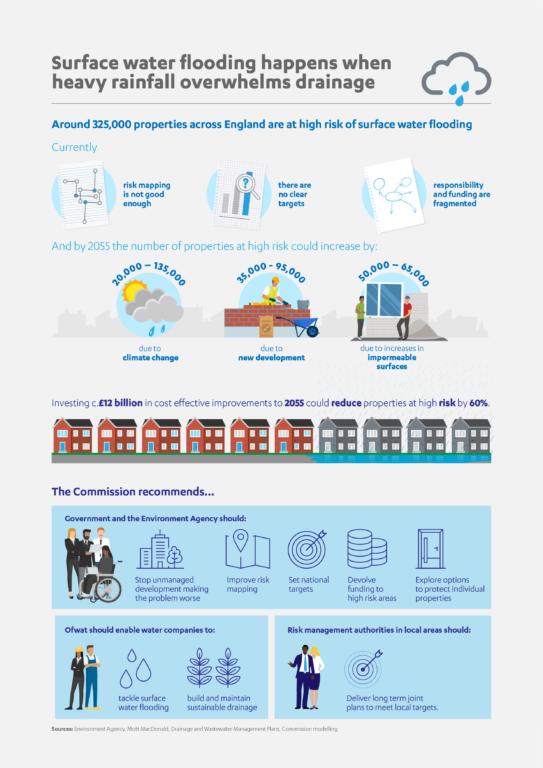

Surface water flooding is a potential risk to many homes and businesses in England. Currently around 325,000 properties are in areas at the highest risk – meaning there is a more than 60 per cent chance they will flood in the next 30 years. Without action, up to 295,000 more properties could be put at risk.

Whatever the figures, such modelling masks the human cost of floods. The impact of a sudden flooding incident on health, livelihoods and wellbeing for affected residents and businesses can be profound. And if you’re in that situation, you don’t really care where the water has come from – you just want it to stop.

Surface water flooding is the flood risk we know the least about. It is highly localised, and hard to predict. A highly local problem needs local solutions.

This report sets out how we can better identify the places most at risk and reduce the number of properties at risk there. This will mean devolving funding to local areas at the highest risk, and supporting them to make long term strategies to meet local targets for risk reduction.

At a national level, there is a need for the Environment Agency to expand its strategic oversight role in relation to surface water flooding. It will also be vital that Ofwat enables water and sewerage companies – who own and operate underground drainage on which we will rely – to invest in solutions to address surface water flooding, including nature based drainage systems. This will require them to work closely with local authorities to protect the people in the areas they serve.

Such an approach also depends on reducing the amount of water that enters drains in the first place, as well as building new infrastructure to increase future drainage capacity. Our report sets out recommendations in each of these areas.

We should not let surface water flooding continue as a stealth threat. We have the means to address it – what’s largely required is impetus for a range of bodies to act, and better coordination between them. Our hope is this report helps provide such an impetus, and a long term framework to help the country weather the coming storms.

Jim Hall Commissioner

Sadie Morgan Commissioner

Julia Prescot Commissioner

Next Section: Executive summary

Around 325,000 English properties are currently at high risk of flooding caused by heavy rainfall. Known as ‘surface water flooding’, this type of flooding it can cause major disruption to people’s lives and livelihoods. Without action, climate change and urbanisation could put an additional 230,000 properties at high risk by 2055. Action is needed to both increase the capacity of pipes and sewers and capture more rainwater before it enters them.

Executive summary

Around 325,000 English properties are currently at high risk of flooding caused by heavy rainfall. Known as ‘surface water flooding’, this type of flooding it can cause major disruption to people’s lives and livelihoods. Without action, climate change and urbanisation could put an additional 230,000 properties at high risk by 2055. Action is needed to both increase the capacity of pipes and sewers and capture more rainwater before it enters them.

Surface water flooding is highly localised and requires local knowledge and solutions. But local areas currently have to bid for funding for schemes to address it, and do not have local targets, or plans formed jointly across all the relevant organisations including water and sewerage companies.

There need to be long term targets for surface water flood risk reduction, devolved funding to the areas at highest risk, and costed joint plans at a local level. It is not affordable to eliminate surface water flood risk everywhere, but a more focussed and coordinated approach can significantly reduce the numbers of properties that would otherwise be at risk.

The Commission recommends that:

- government acts to mitigate the impact of urban development on surface water flooding

- the Environment Agency should improve identification of the highest risk areas, drawing on local maps and models

- government should set a long term target for a reduction in the number of properties at high and medium risk of surface water flooding

- government should clarify in its strategic priorities that Ofwat should enable water and sewerage companies to invest in solutions to manage surface water flooding, including nature based solutions where appropriate

- in high risk areas, local authorities, water and sewerage companies and, where relevant, internal drainage boards, should be required to develop costed, long term, joint plans to manage surface water flooding, including local targets for risk reduction, assured by the Environment Agency with input from Ofwat

- government should devolve public funding to upper tier local authorities in the new flood risk areas based on their level of risk

- for properties remaining at high risk of flooding, government should explore options for funding property level measures.

Some of these recommendations will require changes to current flood risk management arrangements. It is for government to decide how best to make these changes.

Around 325,000 English properties are already in areas at high risk of surface water flooding

While surface water floods tend to lead to lower water levels and result in lower damages than river and coastal flooding, they can cause major disruption to people’s lives and livelihoods. In July 2021, widespread flooding in London affected over 1,500 properties, as well as health infrastructure and transport networks.

Around 325,000 properties in England are in areas that currently have a more than 60 per cent chance of being affected by surface water flooding in the next 30 years (‘high’ risk), and a further 500,000 are in areas that have a similar chance of being affected in the next 100 years, not considering the impacts of climate change or new development. Over 85 per cent of these properties in high risk areas are in cities and towns. Flood risk management is devolved to the governments of Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland.

Climate change and urbanisation are set to put more properties at risk

The number of properties in areas at high risk is set to increase by 2055, including:

- an increase of around 20,000-135,000 properties in areas at high risk due to the impacts of climate change, which will increase the intensity and frequency of heavy rainfall

- an increase of around 35,000-95,000 properties due to new development putting more pressure on drainage systems.

A further 50,000-65,000 properties may be put in areas at high risk due to unplanned increases in impermeable surfaces (e.g. front gardens being paved over), which, alongside new development, is part of ‘urbanisation’ – the conversion of natural (often permeable) environments to urban ones where rainwater cannot enter natural drainage systems.

Government should act to mitigate the impact of urbanisation

New developments have a legal right to connect to existing drainage infrastructure for surface water, which can increase the volume of rainwater that flows into drainage. Current processes do not do enough to encourage new developments to properly mitigate this impact.

In response to the 2007 Pitt Review, the government enacted, but did not implement, legislation in 2010 to improve the planning and delivery of surface water drainage in new development. The proposed changes in Schedule 3 to the Flood and Water Management Act 2010 included making sustainable drainage systems a legal requirement for most new developments and amending the right to connect to public sewers. However, government decided not to implement Schedule 3 in England, in favour of strengthening planning policy in 2014. In 2022, the government reviewed whether to implement Schedule 3 in England. A decision is still pending.

Recommendation 1

By the end of 2023, government should implement Schedule 3 of the Flood and Water Management Act 2010 and update its technical standards for sustainable drainage systems

Government should also consider whether and how to control unplanned increases in impermeable surfaces. Government has three main options: controls, incentives, and public education. Alternatively, government could accept that it will continue to increase the risk of surface water flooding, and factor its impacts into targets, plans and funding. Government should carry out a comprehensive review and decide on the best course of action by the end of 2024.

Recommendation 2

Government should undertake a comprehensive review of the effectiveness of all available options to manage unplanned increases in impermeable (or hard) surfaces, and their costs and benefits. By the end of 2024, government should decide whether policy changes are required to reduce the impacts on surface water flooding or adjust investment levels for flood risk reduction accordingly

Drainage systems must be improved to protect properties in the coming decades

The recommendations above will help reduce the amount of rainwater that would otherwise enter drainage systems. However, drainage systems will still need to be effectively maintained and enhanced to reduce the number of properties already at risk, and help prevent further properties being put at risk, for example as a result of climate change.

‘Drainage systems’ usually include a mix of interventions above and below the ground. Conventionally engineered drainage systems incorporate above ground gullies, channels and drains that convey water to piped underground systems and storage tanks. In England, storm water is mostly drained in the same underground sewers (‘combined’ sewers) that convey wastewater to treatment works. Some above ground solutions – such as green roofs, ponds and rain gardens provide additional environmental and social benefits.

Interventions should be considered following the ‘solutions hierarchy’. This prioritises maintenance and optimisation, followed by above ground interventions, with below ground interventions (pipes and sewers) considered last. This ensures lowest cost options are considered first and maximises the opportunity to deliver wider benefits such as biodiversity.

The recommendations below set out changes in governance and funding to improve the capacity of drainage systems, and to protect properties when flooding does inevitably occur.

Processes to identify the places most at risk should be improved

The Environment Agency supports upper tier local authorities to identify areas where there is a ‘significant’ risk of surface water flooding – known as ‘Flood Risk Areas’. These are reviewed every six years, with the next review planned for 2023.

One of the sources of data the Environment Agency uses to identify Flood Risk Areas is the National Flood Risk Assessment. The first National Flood Risk Assessment took place in 2004. The second is due to be published at the end of 2024 and will provide an updated national flood risk map based on better modelling and data.

Government should consider delaying the next review of flood risk areas to 2025, to allow the Environment Agency to use the results of the second National Flood Risk Assessment when identifying new flood risk areas. This would provide a better basis for identifying those areas at highest risk and for directing future interventions and investment.

The Environment Agency also produces a nationwide map of surface water flooding risk, the ‘Risk of Flooding from Surface Water Map’. It is broadly accurate at a high level, but more granular local data would improve the reliability of risk mapping at the street or property level, giving government and the public a better understanding of risk.

Currently only 35 out of 95 local authorities in Flood Risk Areas have modelling integrated into the national map. There is also no requirement to make local modelling interoperable with Environment Agency maps and models. Government should support local authorities to develop interoperable flood risk maps and models to appraise potential interventions and review the case for commencing provisions in the Flood and Water Management Act 2010 that would provide powers to sanction authorities that do not share data, so that the Environment Agency can include it in the national mapping.

Recommendation 3

Government should:

- require the Environment Agency to use the results of the second National Flood Risk Assessment in 2024 to identify new flood risk areas

- from 2025, require upper tier local authorities, water and sewerage companies, and other relevant authorities in the new flood risk areas to, where necessary, develop detailed local risk maps that can be integrated into the Environment Agency’s national map, and models that can be used to plan future management of surface water flooding.

Government should set national risk reduction targets to drive and monitor progress

While the government has set goals for overall flood risk reduction and property protection by 2027, there is no quantifiable long term target for reducing the risk of surface water flooding. The lack of common goal limits progress and prevents effective monitoring.

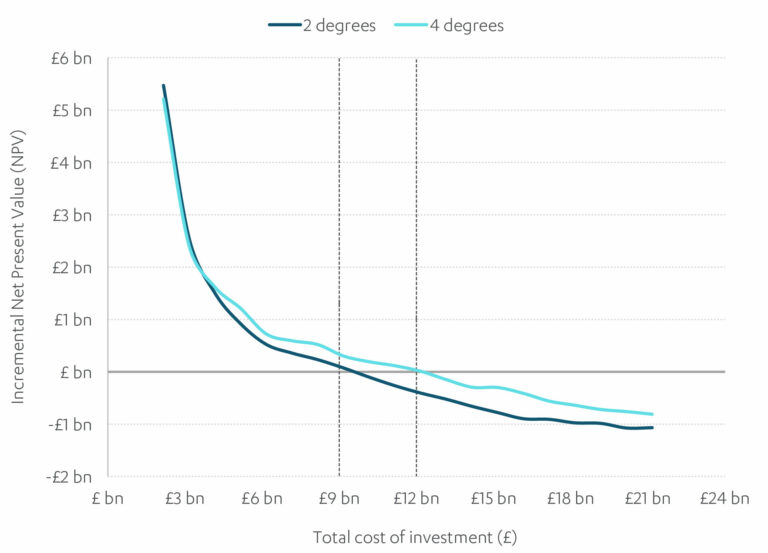

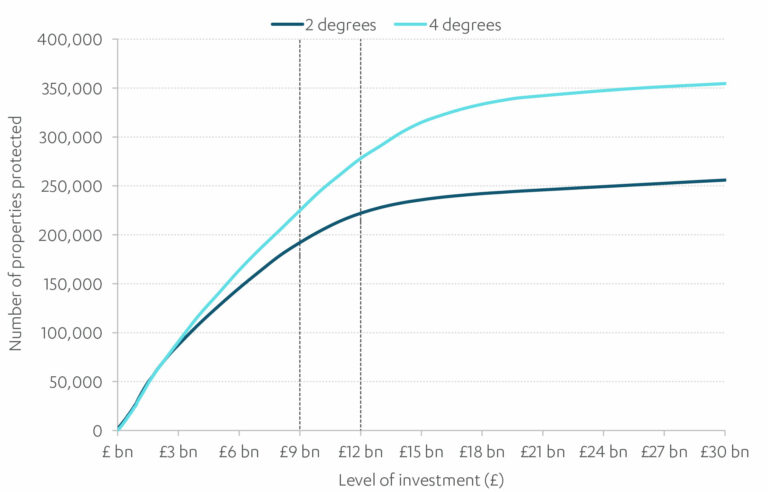

Government should set a national target for risk reduction. Identifying such a target – which would be measured by the number of properties remaining at different risk levels – requires consideration of what is achievable, cost beneficial, and affordable. Modelling carried out on behalf of the Commission indicates that investing about £12 billion over 30 years in cost effective drainage infrastructure measures could reduce the number of properties that would otherwise be at high risk of surface water flooding in 2055 by around 60 per cent. The investment would come largely from public sources and water and sewerage companies based on who is best placed to intervene and who benefits. However, this amount is only indicative, and government should assess the appropriate level itself based on improved Environment Agency mapping and modelling, and considering the potential risk reduction that can be achieved by all types of flood risk protection, including individual property protection.

To drive and monitor progress at the local level, upper tier local authorities, water and sewerage companies, and, where relevant, internal drainage boards in the new flood risk areas should identify quantifiable local targets for reductions in surface water flooding – and the flood damage avoided – as part of their single joint plans (see below).

Recommendation 4

By early 2025, government should set a long term target for a percentage reduction in the number of properties at high and medium risk of surface water flooding

Recommendation 5

The government should require risk management authorities in the new flood risk areas to agree appropriate local targets by mid 2025

Water and sewerage companies should play a key role in reducing risk

Water and sewerage companies will play a key role in reducing surface water flood risk, by improving drainage. Water and sewerage companies have a duty to provide, improve and extend public sewers, and to cleanse and maintain those sewers to ensure that their areas is, and continues to be, effectually drained. However, this duty has tended to be interpreted as meeting the entitlement for property owners and developers to connect to public sewers to discharge surface water, and addressing sewer flooding. Government should clarify in its strategic priorities for Ofwat that it should enable water and sewerage companies to invest in solutions to manage surface water flooding.

The focus of investment will also need to change. Private investment from water and sewerage companies’ customer bills has largely funded below ground drainage, such as pipes and sewers, although this is starting to change. Water and sewerage companies should continue to be encouraged to deliver both above and below ground solutions, and Ofwat should ensure its methodology for the next Price Review period in 2024 creates a level playing field for below and above ground interventions, including sustainable drainage systems.

Recommendation 6

Government should:

- clarify in its strategic priorities for Ofwat that it should enable water and sewerage companies to invest in solutions to manage surface water flooding including sustainable drainage

Single, costed, joint plans

Upper tier local authorities are the main organisations responsible for managing the risks of surface water flooding.

Upper tier local authorities, water and sewerage companies and, where relevant, internal drainage boards in the new flood risk areas should develop and deliver long term, costed, joint plans, setting out local targets for flood risk reduction. They should replace Local Flood Risk Management Strategies and inform water and sewerage companies’ business plans.

The plans should set out a common vision, identify quantifiable local targets, assign clear roles and responsibilities, and contain a costed programme of public and private investment for the next five years. The Environment Agency should review and assure the joint plans, with input from Ofwat and support from Regional Flood and Coastal Committees, by 2026.

To develop and deliver joint plans effectively, it will be critical that all authorities involved, including the Environment Agency and local authorities, have the right funding and capacity to fulfil their roles.

Recommendation 7

Government should require:

- upper tier local authorities, water and sewerage companies, and, where relevant, internal drainage boards in the new flood risk areas to produce and deliver costed, joint investment plans for managing surface water that achieve the agreed local objectives and follow the ‘solutions hierarchy’

- the Environment Agency to review and assure the final plans with input from Ofwat and support from Regional Flood and Coastal Committees, and publish data on progress against local and national targets

- joint plans to be completed by 2026 and revised every five years following the review of flood risk areas the year before, and to inform the following Ofwat Price Review.

Devolved local funding for local flood risks

Local authorities making long terms plans for reducing flood risk in their areas require greater certainty on funding. To support long term planning, government should devolve funding to upper tier local authorities in or containing new flood risk areas, for the purposes of managing surface water flooding along with other local flood risks. This will help to provide the confidence to invest resources in planning, building capacity and identifying partnership funding to deliver programmes of interventions. It will also remove the need to bid to the Environment Agency for grant funding for surface water flooding interventions in the new flood risk areas.

The devolved budgets should initially be set for the five years from 2026-2031 and communicated prior to the development of the joint plans. Allocations could be calculated based on the Environment Agency’s assessment of the level of risk in each new flood risk area. While the additional public investment is not a significant increase on current levels, devolving this funding to local areas should ensure it is spent more effectively, as local bodies are best placed to understand local risks and solutions.

Recommendation 8

By the end of 2025, government should devolve public funding to upper tier local authorities in or containing new flood risk areas, based on the Environment Agency’s assessment of the levels of risk in each new flood risk area. The funding allocation should be reviewed every five years, in line with single joint plan cycles

There should be support for properties remaining at risk

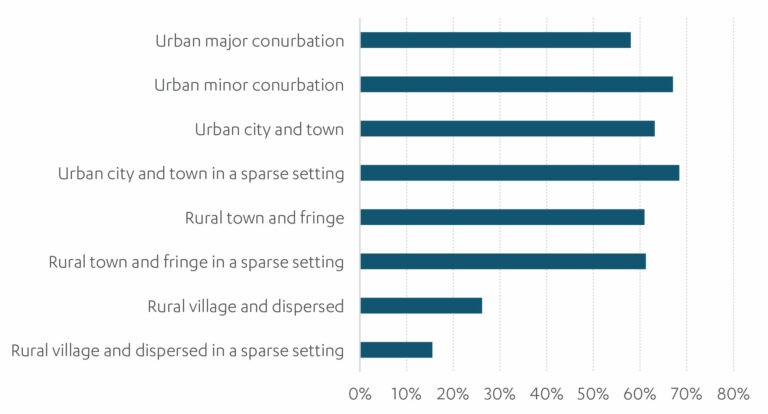

It is not possible to protect all properties at high risk of flooding by delivering cost beneficial investments. The Commission’s modelling estimates that 170,000 – 200,000 properties are in areas that will remain at high risk in 2055. More properties will be protected in cities, both as a total, and as a proportion of properties at high risk.

However, other interventions, such as individual flood barriers or flood insurance, may still be cost beneficial for properties where infrastructure interventions may be less beneficial. This is because flood infrastructure interventions are most cost effective where properties at high risk are densely clustered. However, the costs of surface water flood protection should not automatically fall to individual property owners or occupants simply because of where they live.

Recommendation 9

By the end of 2024, government should explore options for funding property level measures for those properties that remain at high risk of surface water flooding because improving drainage infrastructure is not cost effective.

Next Section: 1. Surface water flooding

Around 325,000 properties across England are in areas at high risk of surface water flooding, particularly in towns and cities. As climate change increases the intensity of rainstorms, and a growing population increases urbanisation, the risk of surface water flooding will increase. While surface water flooding tends to have a slightly lower impact than river and coastal flooding, it is still disruptive, and can be dangerous.

1. Surface water flooding

Around 325,000 properties across England are in areas at high risk of surface water flooding, particularly in towns and cities. As climate change increases the intensity of rainstorms, and a growing population increases urbanisation, the risk of surface water flooding will increase. While surface water flooding tends to have a slightly lower impact than river and coastal flooding, it is still disruptive, and can be dangerous.

High risk properties are in areas that have at least a 1 in 30 chance of flooding every year. A further 500,000 properties are in areas that have at least a 1 in 100 chance of flooding every year.

In the coming decades the number of properties in areas at high risk could increase by:

- 20,000-135,000 due to increases in intensity of rainfall due to climate change of two to four degrees above pre-industrial levels

- 35,000-95,000 due to new development.

An additional 50,000-65,000 more properties may also be put at risk due to increases in impermeable surfaces in urban and suburban areas (e.g. if front gardens are paved over). There may be overlaps between properties in these risk categories.

1.1 Surface water flooding

Surface water flooding – also referred to as pluvial or flash flooding – happens when there is so much rain that it cannot drain away quickly enough, either because drainage networks reach capacity and overflow, or because they are not operating at full capacity due to blockages in pipes and sewers, or in above ground drainage like gullies. Instead of draining away, the rainwater collects at low levels and causes flooding.1 Surface water flooding can occur in rural and urban settings.

Surface water flooding is caused by a combination of factors including rainfall, soil permeability, drainage system capacity and maintenance, physical barriers and topography.2 It is usually localised, hard to predict,3 disruptive to homes and business and can pick up pollutants that drain into rivers and coastal waters (especially if it causes sewers to flood).4 Surface water flooding can have serious impacts, including on lives, livelihoods, environmental quality, and public health.

More detail on the properties and areas surface water flooding affects is set out in Chapter 2.

1.2 Around 325,000 properties are at high risk

Around 325,000 properties – 1.1 per cent of properties in England – are in areas at high risk of surface water flooding. Areas at high risk currently have at least a 1 in 30 chance of flooding every year, equating to a more than 60 per cent chance of flooding at some point in the next 30 years. More properties are in areas at high risk of surface water flooding than of river and coastal flooding combined, which the Environment Agency estimates at around 200,000 properties.5

A further 500,000 properties in England are in areas at ‘medium’ risk (less than a 1 in 30 chance but greater than a 1 in 100 annual chance of flooding), meaning they have a more than 60 per cent chance of flooding in the next 100 years under current circumstances, not considering the impacts of climate change or new development.

Figure 1.1: Around 325,000 properties are at high risk of surface water flooding

Properties (residential and business) at ‘high’ or ‘high or medium’ risk of surface water flooding

| Risk level | Annual chance of flooding | Total properties in areas at this risk level | As a percentage of properties in England |

|---|---|---|---|

| High | 1 in 30 or more | 325,000 | 1.1% |

| High or medium | 1 in 100 or more | 825,000 | 2.5% |

Source: Commission interpretation of Environment Agency Flood risk maps for surface water: how to use the map; Commission calculations based on Sayers et al.

There is no comprehensive record of surface water flooding incidents across England. Where this has been attempted, the estimates tend to rely on media reporting or similar.6 7 Since the Floods and Water Management Act 2010, councils undertake more comprehensive investigations into flood incidents. These investigations provide more detail on causes and impact, including assessing whether individual floods were due to very intense rainfall, or poor maintenance or a combination of factors. However, these investigations are inconsistent in quality and are not collected centrally.8

Roles and responsibilities

The key organisations involved are:

- Upper tier local authorities (unitary authorities or council councils) are the main organisations responsible for managing surface water flood risk. They are designated as Lead Local Flood Authorities and required to develop, maintain, apply and monitor a strategy for local flood risk management in their area

- Highway authorities, which include local highway departments in unitary and county councils and National Highways, and are responsible for draining highways or adjoining land

- District councils (including borough councils) in areas with no unitary authority, which are the local planning authority and are required to consider flood risks when developing local plans and assessing planning applications from developers

- Water and sewerage companies deliver and maintain clean water and sewerage services and have a duty to provide, improve and maintain a public sewer system to effectually drain their areas. They are distinct from ‘water only’ companies, who are only responsible for supplying water to properties and not for drainage.

- Internal drainage boards are independent public authorities that manage water levels in low lying, mostly rural areas, to protect agriculture and the environment.

- The Environment Agency is the non-departmental public body with strategic oversight of all flood sources and is directly responsible for managing flood risks from main rivers, the sea and reservoirs.

- The Department for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs is the government department responsible for flood risk management policy in England.

- Ofwat is the economic regulator for the water sector in England and in Wales. Ofwat scrutinises water companies’ business plans and sets performance commitments for water companies to reduce sewer flooding.

- Regional Flood and Coastal Committees provide a forum for local and regional authorities to coordinate regional activities. They approve Environment Agency requests to raise local levies or implement regional programmes of investment.9

All of these (except Defra, Ofwat and Regional Flood and Coastal Committees) have legal responsibilities for surface water flooding as ‘Risk Management Authorities’ and are required to cooperate.10

Flood risk management is devolved to the governments of Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland. Arrangements in the devolved nations are set out in the Commission’s Second National Infrastructure Assessment: Baseline Report.11 This study only considers England.

Surface water flooding tends to be concentrated in specific places, for example in natural basins, or areas that are largely paved over so water can’t drain away into the soil. The causes of surface water flooding are often similar in rural and urban areas. However, the impact of runoff from fields onto roads is often an important factor in more rural areas.12

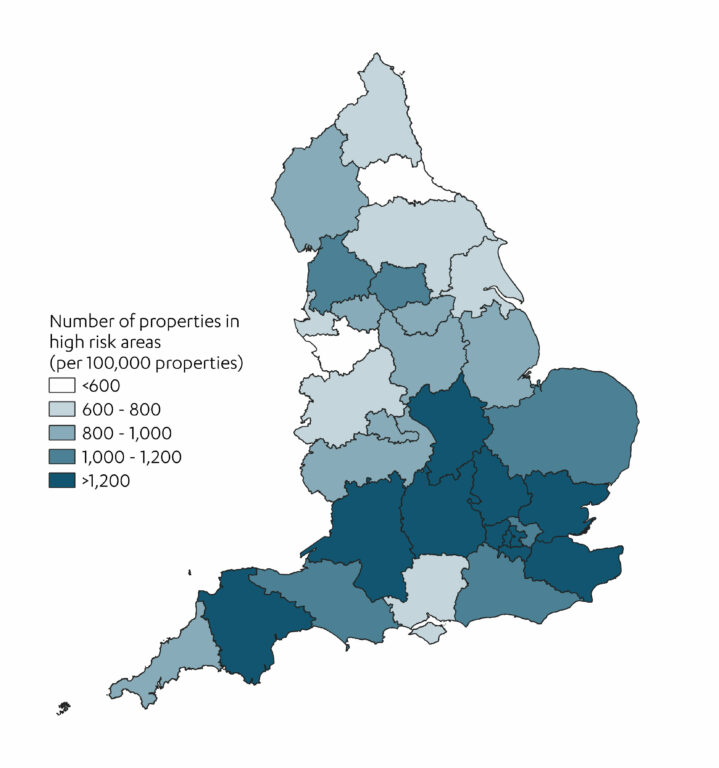

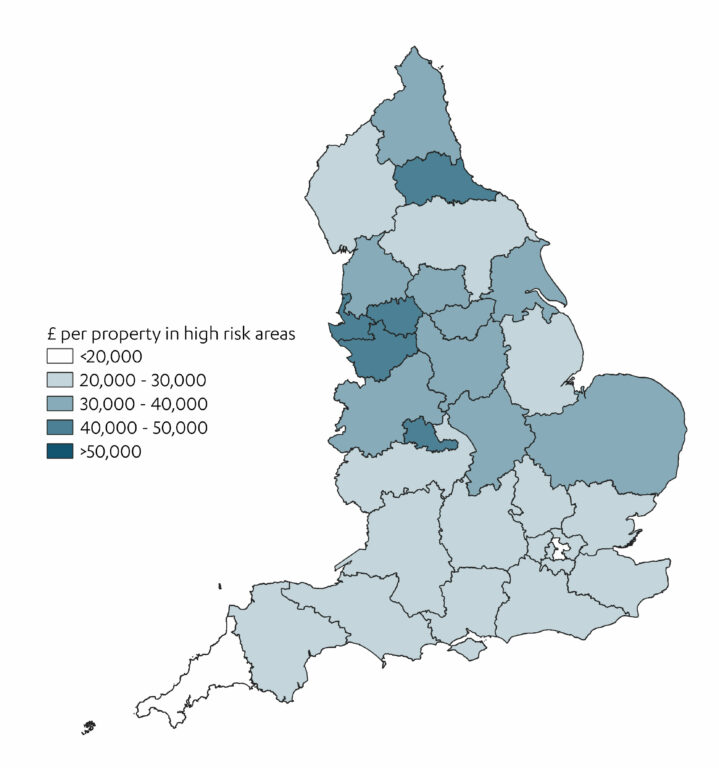

Figure 1.2 shows the number of properties in areas at high risk per 100,000 properties, by region. This shows that there are high risk areas across England. The proportion of properties at high risk does not appear to be entirely correlated either to the most densely populated areas, or to the areas with the highest rainfall (usually in the west). This is because the risk of surface water flooding is related to multiple factors, including the intensity of rainfall, the permeability of the surface on which it falls, and the capacity of the surrounding drainage system.

Figure 1.2: There are high risk areas across England

Number of properties in areas at high risk of flooding per 100,000 properties, by the Office for National Statistics’ ‘International Territorial Level 2’ regions

Source: Commission calculations based on Sayers et al.

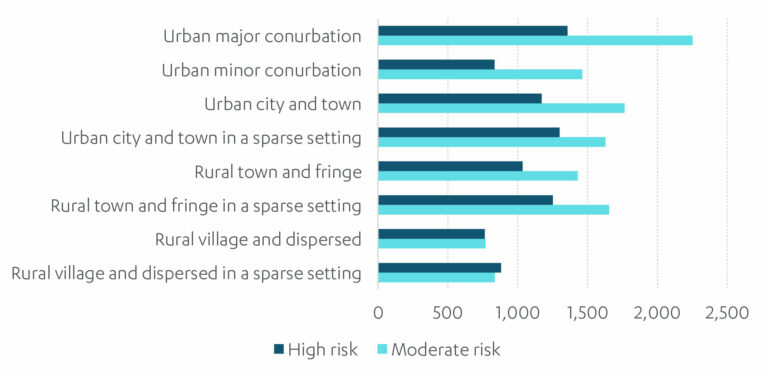

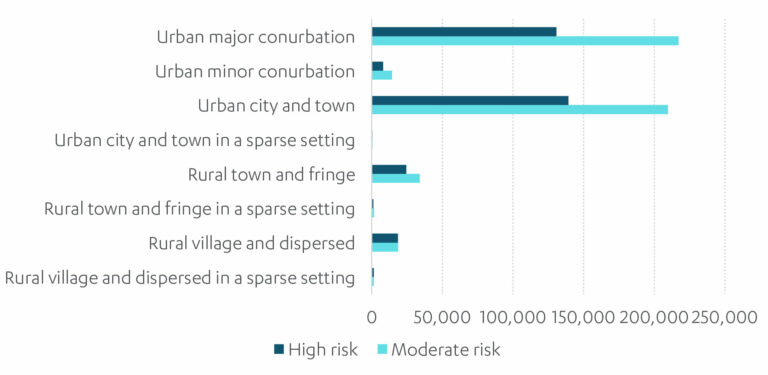

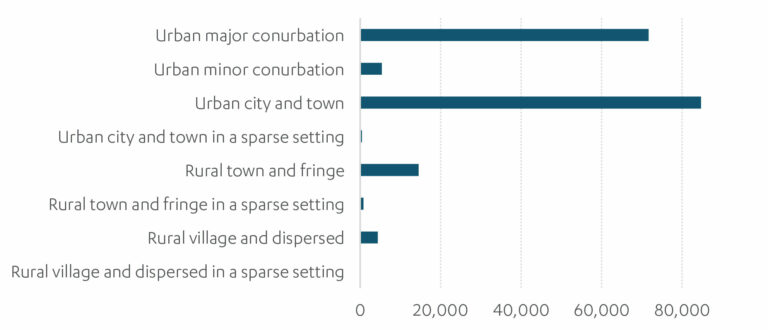

Over 85 per cent of the number of properties in areas at high risk of surface water flooding are in towns and cities. While the proportion of properties in areas at high risk of surface water flooding per 100,000 properties is roughly the same in villages, towns and cities, more properties are in towns and cities overall, and properties in towns and cities are more likely to be in areas at medium risk of flooding than those in smaller villages or rural areas. Therefore, the biggest challenge is in towns and cities, and interventions there are likely to protect the most properties.13

Figure 1.3: High and medium risk properties tend to be concentrated in cities and towns

Properties at risk per 100,000 (top) and in total (bottom), by settlement type and risk level

Source: Commission calculations based on Sayers et al.

Public awareness of surface water flooding is low

The Commission asked BMG to carry out social research on surface water flooding to inform this report. The social research consisted of an online survey of a nationally representative sample of over 2,000 adults in England, and three online focus groups to explore the topic further.

The survey found that:

- Surface water flooding is not well understood: Only 20 per cent of survey respondents were confident they knew what surface water flooding meant and it was very commonly confused with river and coastal flooding.

- Flooding is not a concern for most households: Flooding (from any cause) came ninth on a list of 11 concerns about damages to the home and disruptions to life, below fire, burglary, and burst pipes, and was picked in the top three concerns by only 14 per cent of participants. Even amongst those participants with experience of flooding, only a third ranked flooding in their top three concerns.

- Everyone should pay some of the cost of reducing surface water flood risk: Forty-two per cent of survey participants thought people should all pay the same amounts to protect properties at risk of flooding (irrespective of individual risk), while 25 per cent believed people living in properties at greater risk of flooding should pay more than those less at risk. Participants thought people living in higher risk properties should make some additional contribution to their flood protection.

- Few people think they might need property level protection: A majority of participants were unwilling to install flood resilience measures in their home. The most common reason for this was that participants thought they did not need it.

The full social research report is published alongside this report.14

1.3 Surface water flooding can be extremely disruptive

Surface water floods tend to lead to lower water levels and result in lower damages than river and coastal flooding.15 But even flooding with low water levels can cause major disruption to people’s lives, damaging homes and businesses and affecting people’s wellbeing.

In extreme cases, surface water flooding can even lead to loss of life. This was seen in September 2021, when Hurricane Ida led to flooding in New York City, killing 13 people, 11 of whom were in basements.16 Recent events in England have been less extreme, but have still caused major disruption, see box below.

Surface water flooding also often takes people by surprise – where it happens depends on where rainfall is heaviest, and where that rainfall collects when it cannot drain away. People living near rivers or coasts tend to be more aware of the potential risk. Surface water flooding is also hard to predict, and advance warnings are almost impossible because it can happen very quickly after sudden intense rainfall (hence the term ‘flash flood’) and tends to be localised.17 This can mean people have less time to prepare.

Surface water flooding has been recognised by the government as a key risk and was added to the national risk register in 2016.18

Surface water flooding in England

Examples of surface water flooding incidents throughout the last decade include:

- London, July 2021: Widespread flooding affected 24 of London’s 32 boroughs,19 with over 1,500 properties flooded.20 This affected homes, businesses, health infrastructure and transport networks.21 Further flooding hit London this year, but it is still too early for full reports.

- Rochdale and Greater Manchester, February 2020: There have been repeated events in Rochdale and wider Greater Manchester. Flooding caused by Storms Ciara and Dennis affected numerous properties and local businesses.22

- England, September 2019: Heavy rain caused flash flooding and travel problems, disrupting road and rail travel.23

- The Midlands, May 2018: Storms hit parts of the West Midlands,24 Worcestershire25 and Milton Keynes.26 Collectively this resulted in over 750 properties being flooded across multiple locations.27

- Kent and Cornwall, July 2017: Over 50 properties flooded in at least four areas of Kent,28 and a further 50 properties flooded and roads were damaged in at least two places in Cornwall.29 Some of the areas in Kent were also impacted by flooding in 2015.

- Woking, May 2016: Forty-five properties were flooded, and three schools and one road were closed.30

- Canvey Island, July 2014: Surface water flooding impacted over 200 properties.31

- Newcastle, June 2012: Flooding resulted in over 500 properties being flooded, including shops and schools. Transport networks including roads and trams were also impacted.32

1.4 The number of properties at risk is set to grow

The number of properties at risk from surface water flooding is set to increase in coming decades. The three main drivers of this are:

- Climate change, which will increase the intensity and frequency of heavy rainfall

- New development, which will increase pressure on drainage systems, and may increase the number of properties in areas at risk of surface water flooding

- Unplanned increases in impermeable surfaces, for example property extensions, or paving over front gardens, which increase the volume of water entering drainage systems.

Climate change will increase the intensity and frequency of heavy rainfall

The atmospheric conditions that bring about intense rainfall, while possible at any time of year, tend to occur most often in the summer.33 Although, overall, climate change is likely to mean the UK has hotter, drier summers in future, there is also likely to be an increase in the intensity of summer storms, meaning there will be storms where more rain falls in a shorter period of time. The season for these intense summer storms is also likely to extend into the autumn.34

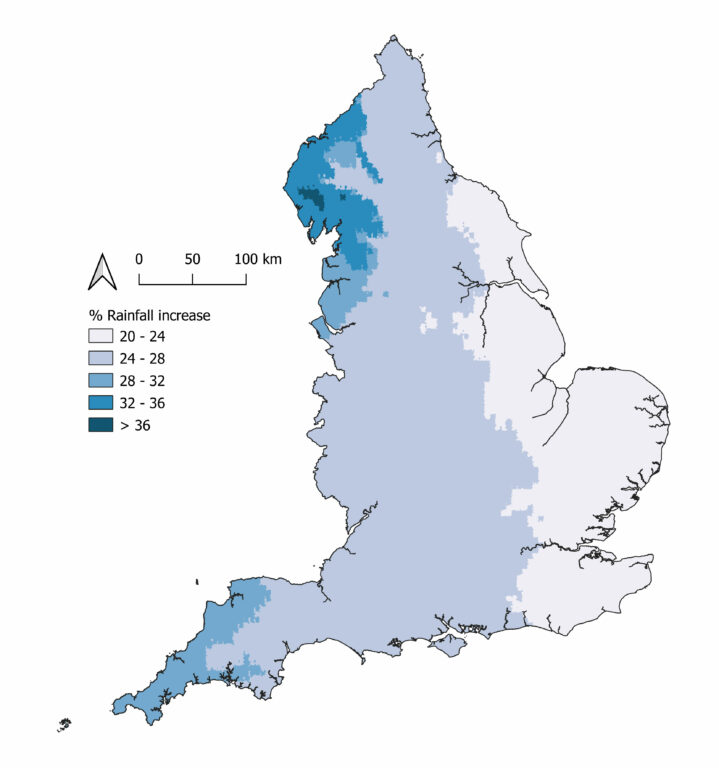

Figure 1.4: Climate change means heavy rainfall is more likely across England

Percentage increase in intense (1 in 30) rainfall by the 2080s, in the 4 degree climate scenario (compared to 1981-2000 average baseline)

Note: Represents the future rainfall scenario for the UK corresponding to a global mean temperature increase by 2100 of 4 degrees

Source: Sayers et al.

The Commission has used two scenarios for climate change: one of a two degree increase in global temperatures by 2100 compared to preindustrial levels, and one of a four degree increase, using the Met Office’s UKCP18 climate projections convection permitting model. Both scenarios imply an increase in intensity and frequency of heavy rainfall, which is greater in the four degree scenario. However, while these projections are widely used, the actual future increase in rainfall is uncertain.35 It will be important to be resilient to a range of scenarios.

Increased volumes of rainfall will mean drainage systems need to drain away water at a much faster rate and are more likely to be overwhelmed and flood. Severn Trent plc (the water and sewerage company) forecast that a 2 degree climate change scenario could increase the number of properties at risk of internal flooding from sewers by 49 per cent by 2050.36

The relative importance of each of these three factors will vary between areas. Changes in precipitation patterns will vary across the country,37 as will rates of new development and increases in impermeable surfaces.38

All three factors will put additional properties at high risk

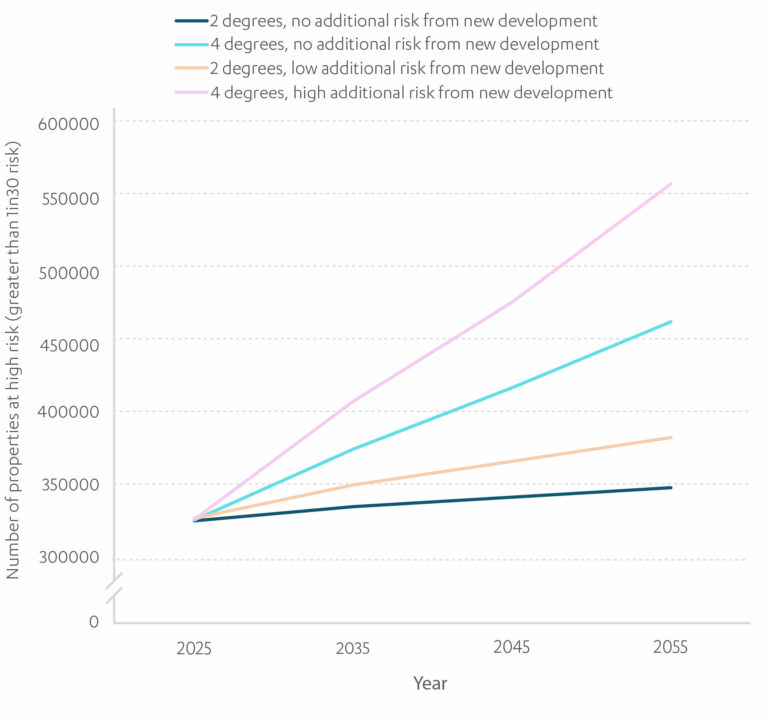

The Commission modelled the potential increase in properties at risk of surface water flooding without intervention due to climate change and new development. The possible increase varies widely – from 20,000 to 230,000 additional properties in areas at high risk by 2055 – depending on the scenario. Figure 1.5 shows four scenarios based on the Met Office’s convection permitting model as set out above:

- two degree climate change, with no additional risk from new development (representing a scenario where new developments are responsible for their own drainage, and so do not add to total risk)

- two degree climate change with some additional risk from new development

- four degree climate change with no additional risk from new development

- four degree climate change with high additional risk from new development.

Figure 1.5: Climate change and new development will increase properties at high risk

Number of properties at high risk over time in different scenarios

Source: Commission calculations based on Sayers et al.

Figure 1.5 shows that climate change that exceeds a two degree increase on preindustrial global averages is the key risk factor in increasing the numbers of properties at risk.

The modelling showed that the number of properties at high risk is set to increase by between 20,000 and 230,000 by 2055, including:

- an increase of around 20,000-135,000 properties in areas at high risk due to the impacts of climate change, which will increase the intensity and frequency of heavy rainfall

- an increase of around 35,000-95,000 properties due to new development putting more pressure on drainage systems.

The third risk factor is unplanned increases in impermeable surfaces (e.g. front gardens being paved over). This may put a further 50,000-65,000 properties in areas at high risk.39 Research suggests that increases in impermeable surfaces have previously occurred in towns and cities at a rate of between 0.4 and 1.1 square metres per house per year.40

Calculations of properties in areas at risk are based on Environment Agency figures which assume drainage is operating at full capacity.41 Blockages or lack of maintenance could put even more properties at risk.

The Commission has not considered the additional risk from new development in its cost modelling in Chapter 4 due to recommendations in the next chapter, which should ensure new developments are responsible for their own surface water drainage.

1.5 The Commission’s surface water flooding study

In November 2021, the government asked the Commission to assess how the relevant authorities in England can better manage and mitigate surface water flooding, with a focus on the role of infrastructure. The government has specifically asked that the study include:

- analysis of the risks of surface water flooding and the opportunities that exist to address these in the short and long term

- determining improvements needed to drainage systems to manage and prevent surface water flooding in urban and rural areas, including through nature based solutions

- considering the optimum cost benefit analysis of infrastructure options and how these can be combined to provide greater resilience and value for money, including through improving current governance arrangements.

The full terms of reference for the study can be found on gov.uk.42

Stakeholder engagement

Over the course of the study the Commission sought input from a wide range of stakeholders including authorities responsible for flood risk management and the public:

- Call for evidence – The Commission published a call for evidence which closed in December 2021. This received 49 responses from water companies, local government, professional bodies, regulators and others.43

- Social research – The Commission carried out an online survey of a nationally representative sample of 2,002 adults in England, plus three focus groups exploring the public’s understanding of risks and priorities.44

- Regional sounding boards – The Commission convened three multistakeholder groups in London, Manchester and the West of England, with two meetings of each.

- Detailed policy discussions – The Commission had bilateral discussions including with government departments, the Environment Agency, Ofwat, water companies, local authorities, internal drainage boards, insurance providers and professional bodies.

- Site visits – The Commission visited drainage systems in Sheffield and Mansfield.

- Expert panel meetings – The Commission had regular meetings with its Climate Resilience Expert Panel, Design Group and Young Professionals Panel.

1.6 Recent and ongoing developments

The Commission’s study interacts with a number of recent and ongoing developments in the governance of surface water flooding. These include:

- The Environment Agency and Lead Local Flood Authorities are updating Flood Risk Management Plans, due by the end of 202245

- Water and sewerage companies are finalising Drainage and Wastewater Management Plans, published in draft in June 2022, and to be published in full in 202346

- Ofwat is finalising its methodology for the next Price Review (PR24), which is due to be published in December 2022, prior to evaluating water company business plans for 2025-30

- The Environment Agency is updating guidance to upper tier local authorities and supporting capacity building

- The government published a Storm Overflows Discharge Reduction Plan at the end of August, including a 25 year £56 billion programme of water and sewerage company investment to address untreated sewage discharges into rivers, lakes and seas47

- The government also published revisions to the flood risk and coastal change planning guidance in August 2022, and is developing indicators to monitor long term changes in flood and coastal resilience, and monitoring the impact of changes to grant funding policy.48

The Commission has taken these into account when developing its recommendations.

Next Section: 2. Surface water management

Surface water can be managed by reducing volumes of water entering existing drainage, managing and improving drainage systems, and planning for when drainage systems are overwhelmed. Changes are needed to carry out all of these more effectively in future.

2. Surface water management

Surface water can be managed by reducing volumes of water entering existing drainage, managing and improving drainage systems, and planning for when drainage systems are overwhelmed. Changes are needed to carry out all of these more effectively in future.

The Commission recommends that government:

- implement reforms to put more responsibility on developers to drain their own developments, to mitigate their impact on the volumes of water entering systems

- review the effectiveness of available options for managing unplanned increases in impermeable surfaces, which increase the volumes of water entering drainage, and decide whether policy changes are required to prevent it adding to the problem

- require local authorities and others to follow the ‘solutions hierarchy’ when improving drainage systems, optimising existing drainage first, then adding above ground solutions before considering new pipes or sewers.

Recommendations to enhance drainage systems and protect properties when floods do happen, in line with the principles set out in this chapter, are covered in Chapters 3 and 4.

2.1 Reducing volumes of water entering existing drainage

New developments should be responsible for their own drainage

New developments can increase surface water flood risk. They have a legal right to connect to existing drainage infrastructure for surface water.49 This can undermine policy requirements for developers to first consider more sustainable ways to manage surface water, and increase the volume of rainwater that flows into drainage.

Planning legislation and policy requires:

- local planning authorities to prepare strategic policies that manage flood risks from all sources, including by steering development to areas with the lowest risk of flooding, and by using the opportunities provided by new development to reduce the causes and impacts of flooding

- new developments of ten or more units and all developments in areas at risk of flooding (from any source, now or in the future) to incorporate sustainable drainage systems, in line with the government’s technical standards

- local planning authorities to seek advice from their corresponding local flood authorities for major developments with surface water drainage.50

National planning policy does set out processes to help reduce the impact of new development on surface water flooding, but these may not do enough to encourage new developments to properly mitigate their impacts on existing drainage. This is because:

- sustainable drainage systems are only required by planning policy, not law, and are not required for minor developments outside areas at risk of flooding, although these make up the majority of planning applications

- policy and standards do not provide a strong incentive to consider sustainable drainage systems early in the design process, which can lead them to be underused by developers

- local planning authorities are not required to seek and receive advise from the lead local flood authority on minor development, even that proposed in areas at risk of surface water flooding

- sustainable drainage systems are approved on a case by case basis by local planning authorities, which can make it hard to plan them over a wider area

- planning applications often lack clear maintenance agreements for sustainable drainage systems, and local authorities can lack the resources to monitor and enforce compliance.51

Local planning authorities have reported surface water flooding in development under ten years old.52

Government should implement reforms to put more responsibility on developers

In response to the 2007 Pitt Review, the government enacted, but did not implement, legislation in 2010 to improve the planning and delivery of surface water drainage in new development. The changes in Schedule 3 to the Flood and Water Management Act 2010 would have:

- made sustainable drainage systems a legal requirement for new development with more than one dwelling, or a construction area of at least 100 square metres

- established a local level approving body for sustainable drainage systems, which would:

- approve proposed drainage systems in new developments and redevelopments, consulting with water companies where necessary

- adopt and maintain sustainable drainage systems that serve multiple properties

- amended Section 106 of the Water Industry Act to make the right to connect a new development to the public sewer conditional on the body approving its drainage.53

However, government later decided not to implement Schedule 3 in England, in favour of delivering sustainable drainage by strengthening planning policy in 2014.54 In the intervening years, this approach has been criticised. In Wales, Schedule 3 legislation has been implemented since January 2019. Evidence suggests that it has improved the delivery of sustainable drainage systems, although there remain issues with funding for long term maintenance.55 In 2022, the government reviewed whether to implement Schedule 3 in England. A decision is still pending.

Government should implement Schedule 3 and update its technical standards for sustainable drainage systems to align with the hierarchy described in section 2.3. Once these changes are made, they should be reflected in relevant national policy and guidance, such as the National Model Design Code and Manual for Streets. This will complement other actions by government and Ofwat to improve processes for the adoption of sustainable drainage systems by water companies.56

Recommendation 1

By the end of 2023, government should implement Schedule 3 of the Flood and Water Management Act 2010 and update its technical standards for sustainable drainage systems

Unplanned increases in impermeable surfaces impact drainage systems

Unplanned increases in impermeable surfaces add to the volume of water entering drainage systems rather than filtering into the soil.57 According to water and sewerage company Drainage and Wastewater Management Plans, unplanned increases in impermeable surfaces (e.g. front gardens being paved over) could be responsible for about 15-20 per cent of the increase in future flood risk to 2055, equating to around 50,000-65,000 more properties in areas at high risk.58

Current planning rules require households to gain planning permission for hard surfacing of domestic front gardens by more than five square metres unless the surface is rendered permeable.59 Installing smaller areas of hard surfacing in front gardens, and the construction of home extensions, outbuildings and decking on up to 50 per cent of the property area, are classed as ‘permitted development’, and do not require planning permission.60

Local authorities can put in place stronger planning policies for development in areas with limited drainage capacity, and withdraw permitted development rights for specific areas on the grounds of its contribution to flood risk by issuing an ‘Article 4 Direction’.61 However, government has increasingly sought to limit the use of Article 4 Directions and sets a high bar for justification and evidence.62 Some local planning authorities have reported uncertainty on how to provide this evidence in Strategic Flood Risk Assessments.63

Water companies can incentivise customers to reduce impermeable areas by adopting ‘Area Based Charging’. This is where drainage charges are made proportionate to the site area that drains into sewers, excluding areas with natural drainage. Some, but not all, water companies have adopted this approach.64 Ofwat is encouraging water companies to trial approaches for extending Area Based Charging to residential customers.65

Government should review options to address increases in impermeable surfaces

Government could control unplanned increases in impermeable surfaces by, for example:

- reducing the extent of permitted development rights for hard surfaces

- via Building Regulations, for example by requiring the use of permeable materials for surfaces in back gardens, or green roofs for home extensions

- encouraging wider adoption of Area Based Charging, or other incentives

- supporting information campaigns run by local authorities and/or water companies to improve public awareness of the impacts of unplanned increases in impermeable surfaces and encourage behaviour change.

Further restrictions would require sufficient local resources for monitoring and enforcement to be effective, and there are already concerns around local authority capacity.66 Building regulations can be rigid and lead to excessive caution from builders.67 And restrictions should not prevent households from creating spaces for electric vehicle charging (although new driveways would not be an issue if they are permeable).

Alternatively, government could accept that unplanned increases in impermeable surfaces will continue to increase the risk of surface water flooding, and factor this impact into its targets, plans and funding, see Chapters 3 and 4. Taking this approach would increase the cost of achieving flood risk reduction targets.

There is a trade off between taking further measures to reduce unplanned increases in impermeable surfaces and allowing them to continue, increasing flood risk. This study could not consider this topic in depth as some of the policy options have implications that go beyond flood risk management. Government should carry out a comprehensive review and decide on the best course of action by the end of 2024.

Recommendation 2

Government should undertake a comprehensive review of the effectiveness of all available options to manage unplanned increases in impermeable (or hard) surfaces, and their costs and benefits. By the end of 2024, government should decide whether policy changes are required to reduce the impacts on surface water flooding or adjust investment levels for flood risk reduction accordingly

2.2 Managing and improving drainage systems

Drainage systems

Rainwater can drain away into the ground or into rivers and eventually the sea, either through natural drainage channels, or manmade drainage infrastructure, see figure 2.1.

Figure 2.1: Diagram of drainage infrastructure

Combined sewers

‘Combined sewers’, owned by water and sewerage companies, which carry both rainwater and wastewater to treatment works, form a large part of the drainage system. Rainwater from around 62 per cent of properties drains into combined sewers.68

The government recently committed to a 25 year £56 billion programme of water and sewerage company investment to address untreated sewage discharges into rivers, lakes and seas that occur when combined sewer storm overflows spill excess wastewater and rainwater, often during heavy rainfall, potentially causing harm to the environment and public health.69 Sewer flooding tends to be caused by blockages and sewer collapses, but is sometimes, like surface water flooding, caused by heavy rain.70 Some combined sewer overflow investment could also help to manage surface water flood risk.71 However, for the around 40 per cent of properties where surface water is drained separately to wastewater, combined sewer overflow investment will not help manage the risk of surface water flooding.

The main types of drainage are as follows:

- Infiltration drainage systems manage rainfall to ensure it soaks and filters into the soil, before returning it to the groundwater. They include permeable surfaces, rain gardens, and depressions or pits where water can drain to (‘infiltration basins’ or ‘soakaways’). They tend to be on private property or owned by public bodies, and can also help improve water quality and support biodiversity.

- Storage drainage systems capture rainfall in small storage areas, typically on private property or roads. They are owned by property owners, water companies or public bodies. They can include playing fields, ponds and wetlands, and can improve water quality and biodiversity, as well as storing extra water.

- Above ground pathways transfer surface water to other drainage systems. They include ‘swales’ (shallow grassy channels), ‘filter strips’ (gently sloping land, particularly at the side of roads), and raised kerbs. These tend to be owned by public bodies, and can provide additional benefits including biodiversity.

- Public sewers, which can drain only surface water or be combined (see box).

- Pipes transport water below ground between locations in the drainage system. These include pipes on private property and those draining roads. These are owned by property owners, water companies, and highways authorities.

- Below ground storage such as storage tanks, oversized pipes or other storage containers store a fixed volume of water. These are owned by water companies. They have limited benefit beyond managing flows in sewers.

The costs of different types of drainage interventions vary widely depending on type and local conditions. Work to support the modelling carried out on behalf of the Commission provides indicative costs for these interventions, including for sewers and sustainable drainage, but they are not directly comparable. This indicates improving sewers to increase capacity can cost between £900,000 and £1,300,000 per kilometre, while typical sustainable drainage systems cost between £5,000 and £7,000 per property (all in 2021 prices). The government’s existing drive to increase the use of sustainable drainage is likely to improve the ability to make comparisons.72

Drainage assets are built to specific standards, which vary depending on their purpose but are usually characterised by the amount of rainfall (measured in terms of intensity and duration) they can cope with, eg highway drainage is usually built to manage rainfall with a 1 in 5 or above chance of happening annually, while modern sewers are required to be built to manage rainfall with a 1 in 30 annual probability.73

The way drainage systems are operated and maintained can mean their day to day capacity is, in reality, less than the designed capacity due to blockages.74

Improving drainage systems: the ‘solutions hierarchy’

The recommendations set out in section 2.1 will help reduce the amount of rainwater that would otherwise enter drainage systems. However, drainage systems will still need to be effectively maintained and enhanced to reduce the number of properties already at risk, and help prevent further properties being put at risk, for example as a result of climate change. The appropriate set of interventions to improve drainage systems will be informed by both the physical environment and the drainage infrastructure already in place.

The ‘solutions hierarchy’ sets out the order in which drainage interventions should be considered to maximise the range of benefits and reduce costs. It prioritises maintenance and optimisation, followed by above ground interventions, with below ground interventions (pipes and sewers) considered last.

The first option should be optimising existing drainage infrastructure, through targeted maintenance and cleaning of existing assets including sewers and gullies, or technological optimisation, including real time control of rainwater in the drainage system during a storm. Starting with optimising existing assets ensures consideration of the lowest cost interventions and can address network blockages that can cause sewer flooding even in relatively low intensity rainfall events. The Commission will consider the maintenance of drainage infrastructure as part of its work on asset management in the second National Infrastructure Assessment.

If existing drainage is not sufficient, above ground interventions, such as rain gardens, ponds and kerbs should be considered next, to manage flows of rainwater, and reduce the volumes of water entering below ground drainage. This will reduce the risk of pipes and sewers flooding, and potentially reduce the cost of wastewater treatment. Considering above ground measures before underground pipes and storage also maximises the opportunity to deliver wider benefits, such as improving biodiversity,75 as well as tending to be cheaper.76 Below ground interventions – additional pipes and sewers – should be the final option considered.

The Commission expects this approach to be followed when single joint plans are developed (see Recommendation 6), and has used the hierarchy to inform its analysis, see Chapter 4. While above ground solutions will not resolve flood risk in many locations, their feasibility should be considered first because of the additional benefits they provide.

Building the evidence base for above ground solutions at scale

As part of this study, the Commission carried out modelling to identify an indicative level of cost beneficial investment (see Chapter 4). The modelling followed the solutions hierarchy set out above.

The level of above ground solutions indicated by the modelling would represent a significant increase compared to current levels. It is broadly equivalent to around 16.5 times the investment in large scale above ground solutions set out in the green recovery fund, which Ofwat described as ‘a step change in the management of surface water’.77 This involves a large scale scheme led by Severn Trent Water to deliver the equivalent of up to 60 per cent of the anticipated future network storage required in Mansfield by 2050 through nature based infrastructure. The scheme will include delivery of assets such as street planters, raingardens, detention basins and permeable paving, and will provide improvements to flooding pathways, as well as delivery of wider environmental and social benefits.

However, the modelling indicated that the majority of the indicative investment would likely go towards below ground solutions, building or replacing 1,100 kilometres of sewer pipe, around 0.4 per cent of current network length.78 In the two degree scenario, investment is slightly less skewed towards below ground solutions.

The skew towards below ground solutions is because there is currently more certainty on the drainage capacity (and therefore flood risk reduction) provided by pipes and sewers, and these form part of water and sewerage companies’ regulated asset bases. More pipes and sewers are needed because they can more reliably drain larger volumes of rainwater. In comparison, there is less data around above ground interventions when delivered at scale, in part because they are not yet widely used in the UK. Where there is uncertainty around the capacity needed, pipes look like a better option.

However, it should be noted that the modelling was designed to maximise flood risk reduction. Above ground solutions can also provide additional environmental and social benefits when they include natural elements like plants and ponds. They should be considered before below ground solutions in order to maximise these benefits.

In practice, there is likely to be scope for even more above ground solutions than the modelling indicates. The exact balance of investment between above and below ground solutions will depend on local circumstances and should be decided in local areas. And as sustainable drainage schemes are implemented more and the evidence base becomes stronger, they may become more attractive.

Government and Ofwat has indicated that they want to facilitate a greater use of nature based solutions. It is important that the regulatory framework for water companies explicitly permits investment at scale in sustainable drainage systems and provides companies with additional surety of funding for these types of solutions where cost effective (see Chapter 4). This will enable the sector to move beyond important pilots such as Mansfield to scaling up nature based solutions where appropriate.

2.3 Planning for when drainage systems are overwhelmed

It is not always feasible or cost effective to build a drainage system that can cope with even the most extreme rainfall events throughout the country, so there will always be instances when they are overwhelmed. Therefore, there need to be plans in place to manage surface water flows when there are extreme rainfall events, to avoid damage to buildings and infrastructure. This can be addressed through landscape resilience measures and property level resilience measures.

Landscape resilience measures divert flooding away from buildings and infrastructure when drainage systems are overwhelmed. Guidance on how to approach design for such events broadly involves changing specific elements of the urban environment to safely route and store surface water flows when the capacity of the drainage system is exceeded.79 Options include using roads to channel water, raising or dropping kerbs to redirect water, and using areas like car parks and open green space for temporary storage. These approaches often require coordination between organisations, and have been used in parts of Cornwall, Oxfordshire and the West Midlands.80 Improved modelling can improve understanding of the places at risk in exceedance events, see Chapter 3. These measures should be considered in the single joint plans, see Chapter 4.

Property level resilience measures include physical measures like flood barriers, sealed air bricks, and small pump units that can help to prevent water from entering buildings or enable quicker recovery after flooding. Flood insurance can also support a quicker recovery. The measures are often recommended when properties suffer from frequent flooding or where other flood management measures are not cost effective. This is covered in more detail in Chapter 4.

Next Section: 3. Identifying the places most at risk and setting targets for improvement

National government, regulators, local government and water companies must work together to identify the places most at risk of surface water flooding and set targets for risk reduction to help track progress. As climate change increases the risk of surface water flooding, this will become even more important.

3. Identifying the places most at risk and setting targets for improvement

National government, regulators, local government and water companies must work together to identify the places most at risk of surface water flooding and set targets for risk reduction to help track progress. As climate change increases the risk of surface water flooding, this will become even more important.

National and local flood risk maps and models do not align. The Environment Agency does not set a national target for reducing surface water flood risk, and the areas most at risk of surface water flooding do not typically identify quantifiable local targets for risk reduction.

The Commission recommends:

- the Environment Agency should use the results of the second National Flood Risk Assessment in 2024 to improve the identification of flood risk areas

- improving local risk mapping in the new flood risk areas and integrate local maps into the Environment Agency’s national model

- government should set a long term target for a percentage reduction in the number of properties at high and medium risk of surface water flooding

- authorities responsible for the new flood risk areas should agree appropriate local targets.

3.1 Identifying the areas at highest risk of flooding

As the risk of surface water flooding increases, it will be vital to have a consistent and rigorous process for identifying the areas at highest risk, based on the best possible data. This will help direct funding and efforts to the places that need them most.

‘Flood Risk Areas’ are not always identified precisely and consistently

The Environment Agency supports upper tier local authorities to identify areas where there is a ‘significant’ risk of surface water flooding – known as ‘Flood Risk Areas’. These are reviewed every six years, in accordance with the Flood Risk Regulations 2009. The next review is planned for 2023.81

The Environment Agency uses its national data to identify indicative flood risk areas based on thresholds for the number of people, services, or properties at risk from surface water flooding per square km. Upper tier local authorities then use their local knowledge to review and refine the proposed areas. The Environment Agency has a last review to ensure its guidance has been applied appropriately and consistently and confirms the final Flood Risk Areas.82

However, the process does not appear to result in consistent outcomes. In one case, a Flood Risk Area has simply been defined using a local authority’s administrative boundaries. In other cases, Flood Risk Areas have square boundaries which do not fully align with the topography of those places.83 These results are counterintuitive, and likely reduce effective coordination across local authority boundaries.

Risk mapping needs to be sufficiently accurate to best deliver protection to areas truly at high risk and encourage joined up working across organisational and administrative boundaries. Government and the Environment Agency should review the criteria used to identify ‘flood risk areas’ and provide greater clarity and consistency in how those areas are defined.

Future processes should take advantage of better data

One of the sources of data the Environment Agency uses to identify flood risk areas is the National Flood Risk Assessment. The first National Flood Risk Assessment took place in 2004.84 The second is due to be published at the end of 2024,85 which falls after the next planned review of flood risk areas in 2023.

The second National Flood Risk Assessment will provide the Environment Agency with an updated national flood risk map, based on better modelling of terrain, and urban and rural drainage rates. It will also reflect better data on flood defences and other assets which alter the flow of water, such as channels and bridges.

Government should consider delaying the next review of flood risk areas to 2025, to allow the Environment Agency to use the results of the second National Flood Risk Assessment when identifying new flood risk areas. This would provide a better basis for identifying those areas at highest risk and for directing future interventions and investment.

Variations in the quality and comprehensiveness of surface water flood risk data

A lack of high quality, comprehensive data is an obstacle to effective surface water management:

- There is variation in the quality and quantity of data on drainage assets: Across the sector, some organisations – whether local authorities or water and sewerage companies – have detailed data on their assets and their performance,86 while data on some assets, such as culverts, may be very limited.87 Where data exists, often it is not shared freely due to commercial, privacy or reputational concerns,88 or is not interoperable.89

- There are inconsistencies in how upper tier local authorities maintain asset registers: Upper tier local authorities are required to maintain registers of assets (theirs and those of third parties) and their condition.90 However the quality and comprehensiveness of these registers vary.91

- There are differing approaches to how upper tier local authorities investigate floods: Upper tier local authorities are usually required to investigate local floods.92 However, there can be inconsistencies between the data collected and the modelling carried out.93

These have been addressed by recommendations in previous reviews, including the 2020 Jenkins Review, which recommended that government and the Environment Agency develop and issue national guidance on asset registers and flood investigations.94 Government has accepted those recommendations, but not yet implemented them.95 The 2022 London Independent Flood Review also recommended that authorities review critical assets and identify ways of monitoring data to inform decision making and prioritisation.96

Upper tier local authorities do not typically produce high quality risk mapping

The Environment Agency produces a nationwide map of surface water flooding risk, the ‘Risk of Flooding from Surface Water Map’. It is broadly accurate at a high level, but it does have major limitations.97 The 2024 National Flood Risk Assessment process will help improve this map. But more granular local data – that aligns with the Environment Agency’s own modelling – would enable flood risk mapping to account for local drainage systems and small topographical changes, such as channels, dropped kerbs, and raised pavements, which can significantly affect where water flows. This data would improve the reliability of risk mapping at the street or property level.98

There are 63 designated Flood Risk Areas in England, spanning an area covered by 95 local authorities. However, not all upper tier local authorities in these Flood Risk Areas produce high quality risk mapping that can be integrated into the model – currently only 35 out of 95 have modelling integrated into the national map. Some upper tier local authorities have been given grants to develop local mapping on a risk basis,99 but otherwise progress has been piecemeal.

Where upper tier local authorities develop their own risk maps and share them with the Environment Agency, they supersede the Agency’s own modelling results.100 However, local authorities do not typically work with other relevant authorities to produce them, and water and sewerage companies and others do not routinely share their asset data, models and maps with upper tier local authorities.101 There is also no requirement to make local modelling interoperable with Environment Agency maps and models.102

The government’s 2018 Surface Water Flooding action plan said that the Environment Agency would “work with Lead Local Flood Authorities, insurance companies and water and sewerage companies about accessing and sharing the data they hold and the modelling they have completed, with the objective of making this information more accessible to the public and using it to improve the surface water maps.”103 The Environment Agency should continue to do this.

The new flood risk areas should be supported to deliver interoperable risk maps

In the new flood risk areas, the relevant upper tier local authorities should be required to work with water and sewerage companies, insurance companies, and, where relevant, internal drainage boards, to develop their flood risk maps and to develop models to appraise potential interventions. Government should support this by providing funding, support and coordination where necessary, and the Environment Agency should work with local authorities to make sure the maps and models align with its own.

These maps and models should then be integrated into the national risk map. This will provide consistency between national and local level maps, improve the process of identifying priority areas of flood risk and enable easier monitoring of progress. In turn this will provide benefits to insurers and lenders, who can more accurately price their products, and to current and prospective property owners who use the national level map. Government should review the case for commencing provisions in the Flood and Water Management Act 2010 that would provide powers to sanction authorities that do not share data so that the Environment Agency can include it in the national mapping. The surface water flood models that are used to create these improved maps will be essential tools for prioritising flood risk reduction measures and developing shared plans (see Chapter 4).

Recommendation 3

Government should:

- require the Environment Agency to use the results of the second National Flood Risk Assessment in 2024 to identify new flood risk areas

- from 2025, require upper tier local authorities, water and sewerage companies, and other relevant authorities in the new flood risk areas to, where necessary, develop detailed local risk maps that can be integrated into the Environment Agency’s national map, and models that can be used to plan future management of surface water flooding

3.2 New targets to reduce properties at risk

The lack of a common goal slows progress and prevents effective monitoring

While the government has set goals for overall flood risk reduction and property protection by 2027,104 there is currently no quantifiable long term target for reducing the risk of surface water flooding, nor a framework to agree one locally.105 The Environment Agency’s 2020 Flood and Coastal Erosion Risk Management strategy does not define clear policy goals for surface water flooding. By contrast, other policy objectives in the government’s 25 Year Environment Plan (although not river and coastal flooding) have clear outcome targets which are being legislated under the 2021 Environment Act.106

The lack of a common goal limits progress. Risk management authorities have no shared commitment to deliver an outcome within a set timeframe, and national policy and strategy does not provide sufficient detail to drive local action and encourage coordination. The various components of a drainage system are designed to achieve different levels of performance, based upon sector specific codes of practice and standards, rather than to achieve a common outcome in terms of risk reduction.107