Second National Infrastructure Assessment: Baseline Report

An analysis of the current state of key infrastructure sectors

Tagged: Design & FundingDigital & DataEnergy & Net ZeroEnvironmentNational Infrastructure AssessmentPlaceRegulation & ResilienceTransportWater & Floods

In brief

This Baseline Report sets out the current state of the UK’s economic infrastructure and identifies key challenges for the coming decades. The Commission will make recommendations to address these challenges in the second National Infrastructure Assessment, to be published in the second half of 2023. The Call for Evidence has now closed.

Since the first Assessment, there has been progress on some issues:

These include full fibre rollout, electricity decarbonisation, drought resilience, infrastructure financing – through the creation of the UK Infrastructure Bank – and design.

However, in other areas, there is more to be done:

- greenhouse gas emissions from economic infrastructure must reduce further, fast

- asset maintenance issues undermine performance in some sectors

- more than three million properties in England are at risk from surface water flooding

- serious pollution incidents from water and sewerage are unacceptably high

- urban transport connectivity varied and is poor in many places.

Future trends and government commitments will bring new challenges:

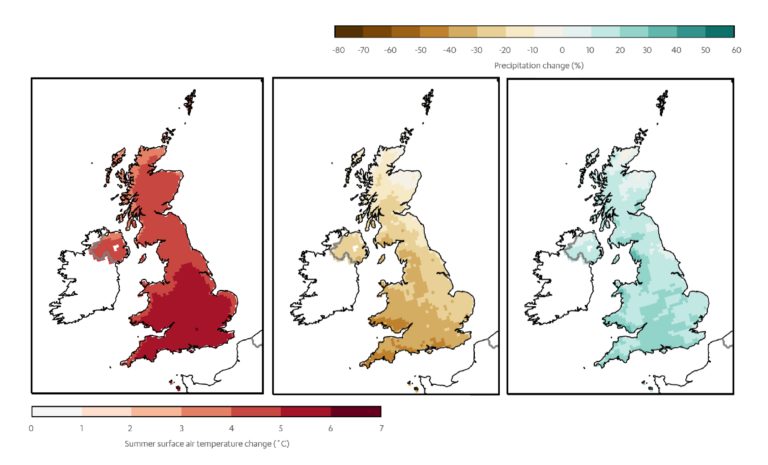

- climate change will make it harder to make and keep infrastructure resilience

- nature is declining at unprecedented rates

- the Covid-19 pandemic may lead to long term changes in where people live and work

- new and emerging technologies will offer opportunities across sectors.

Delivering on these challenges will require bold action, stable plans and long term funding.

The Commission has identified nine key challenges for the second Assessment:

- all sectors will need to take the opportunities of new digital technologies

- the electricity system must decarbonise fast to meet the sixth Carbon Budget

- decarbonising heat will require major changes to the way people heat their homes

- new networks will be needed for hydrogen and carbon capture and storage

- good asset management will be crucial as the effects of climate change increase

- action is needed to improve surface water management as flood risk increases

- the waste sector must support the move to a circular economy

- improved urban mobility and reduced congestion can boost urban productivity

- a multimodal interurban transport strategy can support regional growth.

The Commission has welcomed views on these key challenges in response to the Call for Evidence (now closed). The Commission will also hold events during the Call for Evidence period and in the run up to the second Assessment.

Next Section: Foreword

To build a long term vision for the infrastructure of the future we need to understand where we are today.

Foreword

To build a long term vision for the infrastructure of the future we need to understand where we are today.

This Baseline Report surveys the state of our national systems of digital, energy, flood resilience, water and wastewater, waste and transport.

It enables the Commission to identify the biggest questions about the UK’s readiness for the challenges and opportunities of the future, and to review developments since we published the first ever National Infrastructure Assessment in 2018.

We acknowledge areas of tangible improvement in recent years, contributing to generally good levels of public satisfaction with national infrastructure services. We highlight the progress of the rollout of gigabit-capable broadband, major steps in electricity decarbonisation and the establishment of the UK Infrastructure Bank as examples.

But major challenges remain. Carbon emissions from economic infrastructure must reduce further, and fast. We are not investing sufficiently in maintenance of key assets to ensure their resilience in future, particularly in the face of climate change. Extreme weather also heightens the risk of flooding, with surface water flooding a key risk to many properties. And our transport systems in many places are not good enough.

Inevitably it’s a mixed picture, but that shouldn’t cloud the need for decisive action and the adoption of long term plans supported by adequate funding.

This is categorically not the time for complacency.

To underline this, we have decided that the second Assessment will focus on the three strategic themes of reaching net zero, climate resilience and the environment, and supporting levelling up.

Each pose urgent and wide ranging questions. Each draw broad political and public support for their end goal. Each, however, offer few quick wins or cheap fixes.

So, under the umbrella of the themes, we propose to tackle nine key challenges over the next two years, developing recommendations for the second Assessment, due in the second half of 2023. These challenges range from how we can accelerate work to decarbonise home heating, to how we can improve urban mobility and reduce congestion.

We will now embark on this work – informed by input and insight from industry, political leaders, representative bodies, other organisations across the country and the public – and formulate policy recommendations to put forward to government.

We hope this report prompts discussion, but also encourages optimism: a confidence that, working in a collaborative spirit, the private and public sectors can develop infrastructure solutions to meet the challenges of the second half of this century – so that every part of the UK can share in the rewards of a safer, cleaner, better connected society.

Sir John Armitt, Chair

Next Section: Executive summary

Long term infrastructure policy can help address major future challenges such as reaching net zero, adapting to climate change, reducing environmental impacts, and levelling up across regions. The Commission will make recommendations to address these challenges in the second National Infrastructure Assessment, to be published in the second half of 2023. This document assesses the state of economic infrastructure today and identifies the future priorities for the second Assessment.

Executive summary

Long term infrastructure policy can help address major future challenges such as reaching net zero, adapting to climate change, reducing environmental impacts, and levelling up across regions. The Commission will make recommendations to address these challenges in the second National Infrastructure Assessment, to be published in the second half of 2023. This document assesses the state of economic infrastructure today and identifies the future priorities for the second Assessment.

The Commission has identified three strategic themes for the second Assessment:

- Reaching net zero: All sectors have more to do to reach net zero, particularly transport, where road and rail vehicles all need to become zero emission, energy, where government has committed to decarbonise electricity generation by 2035, and decarbonising heat, which will require major changes to the way people heat their homes.

- Climate resilience and the environment: While economic infrastructure has generally proved resilient to shocks and stresses over recent years, climate change will only increase pressures across all sectors, and infrastructure sectors have significant impacts – both positive and negative – on the environment.

- Supporting levelling up: There is significant variation in the quality of transport provision across England, which can affect economic outcomes, and people’s quality of life. Improving transport provision is therefore key to the government’s levelling up agenda.

All sectors must also take the opportunities offered by new digital technologies.

All of this will require significant levels of investment, which will ultimately be funded by consumers (via bills) or taxpayers. The Commission will carry out cross cutting analysis on all its recommendations for the second Assessment, including considering the overall affordability of required investment, the distribution of costs and savings across groups in society, and who should pay.

This document is the start of a conversation with the public and stakeholders about the country’s infrastructure needs and how to meet them, which will inform the development of the second Assessment. The Commission welcomes responses to the Call for Evidence questions set out in the document, and it will also hold a programme of events to gain new insights and evidence.

The second National Infrastructure Assessment

The Commission carries out a National Infrastructure Assessment once every five years. These set out the Commission’s assessment of long term needs in the transport, energy, water and wastewater, flood resilience, digital, and waste sectors, and recommendations to meet them, including the right policy, regulatory and funding mechanisms. The Assessments are guided by the Commission’s objectives to support sustainable growth across all regions of the UK, improve competitiveness and quality of life, and the Commission’s new objective to support climate resilience and the transition to net zero carbon emissions by 2050. The Assessments take a long term view, looking ahead over the next 10-30 years.

The Commission will publish the second Assessment in the second half of 2023. The second Assessment will build on the first Assessment and the Commission’s wider body of work, much of which is still relevant. It will focus on key challenges not covered in the first Assessment, areas where the Commission’s recommendations need to be updated, or where the Commission needs to address new issues.

The Baseline Report

Progress has been made in some areas since the first Assessment

The first Assessment was published in July 2018. Since then, it has shaped infrastructure policy across sectors. The government’s National Infrastructure Strategy, a formal response to the Assessment, aligned closely with the Commission’s recommendations, and there has been significant progress on many of the recommendations, including:

- access to gigabit capable broadband: the government has set out a clear vision to deliver gigabit capable broadband to at least 85 per cent of UK premises by 2025 – in late 2021 this was well underway, reaching over 50 per cent of premises

- a shift to renewable electricity: there has been a shift towards a highly renewable electricity system, with almost 40 per cent of electricity generated by renewable sources in 2019

- electric vehicles: government has banned the sale of new petrol and diesel cars and vans in the UK from 2030, following the Commission’s recommendation that charging infrastructure should be delivered to enable this shift

- flooding: the government will invest £5.6 billion over the next six years to reduce the risk of flooding, following Commission recommendations

- drought resilience: government and the water industry in England have taken on the Commission’s recommendations to increase water supply and reduce leakage

- the UK Infrastructure Bank: the independent infrastructure financing institution the Commission recommended be established following the UK’s loss of access to the European Investment Bank was launched in June 2021

- design principles: the government endorsed the Commission’s design principles and recommendation for board level design champions on major infrastructure projects.

Infrastructure has continued to perform well in some areas

The Commission’s performance assessment has identified several areas where infrastructure is performing well, including:

- access to mobile connectivity: 92 per cent of the UK landmass is covered by at least one mobile operator, with a funded plan to increase this to 95 per cent by 2026

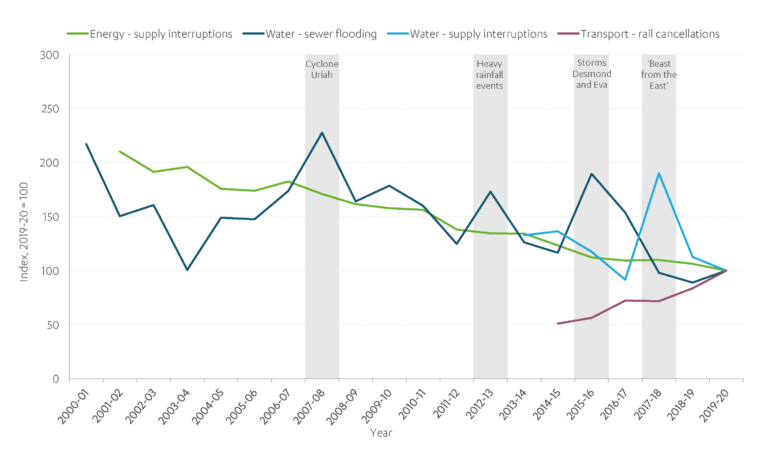

- reliable energy supply: the energy sector delivers electricity and gas of reliable quality to consumers – loss of supply is rare, and interruptions to supply are reducing over time

- access to clean water: the water sector delivers water of reliable quality to homes and businesses across England, with low numbers of service interruptions, and customers are generally satisfied with the water and wastewater services provided.

Social research

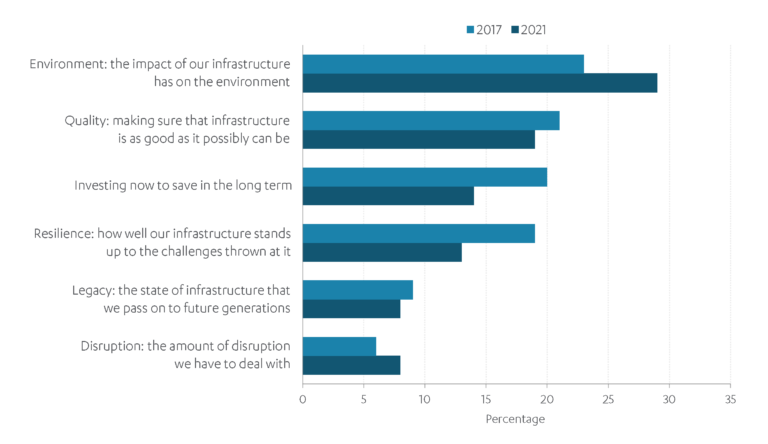

In June 2021, the Commission carried out social research, with a range of respondents from across the UK, nationally representative by age, gender, region and ethnicity.

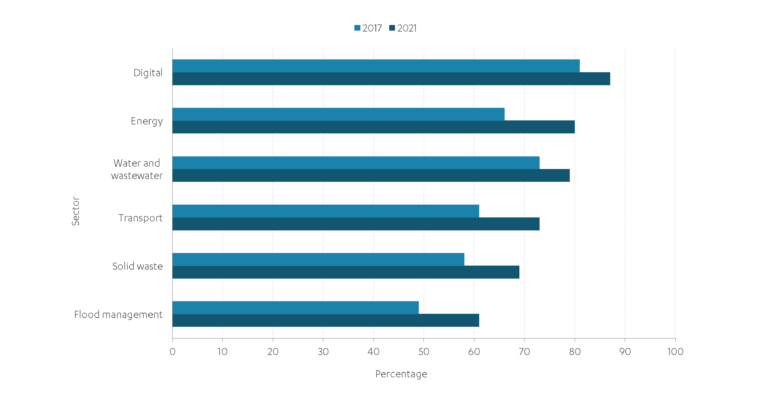

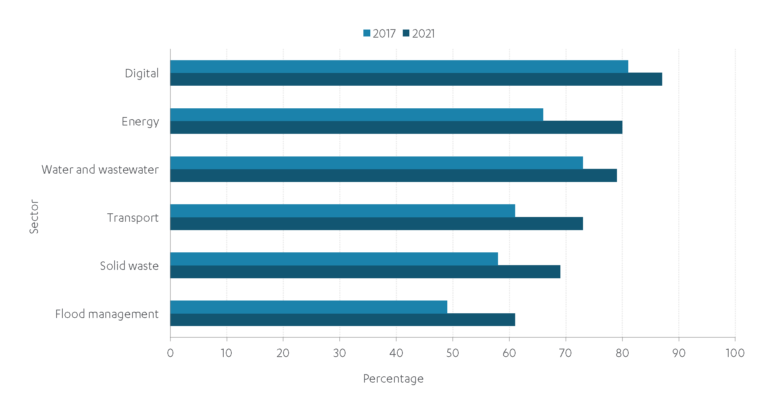

The research showed relatively high levels of confidence from respondents from across the UK that infrastructure will meet people’s needs over the next 30 years, with confidence increasing since the last Assessment. Only two sectors – flood resilience and waste – had lower than 70 per cent confidence, with the digital sector performing particularly strongly. This social research will shape the Commission’s approach to the second Assessment.

Figure 0.1: Public confidence in infrastructure has improved since the first Assessment

Percentage of respondents who were confident that the sector would meet their needs in the next 30 years, in 2021 vs in 2017 (ahead of the first Assessment)

Source: PwC (2021), NIA2 Social Research: Final report

The research also showed that the public increasingly believe that infrastructure should lead the fight against climate change and a plan for infrastructure should consider the impact of infrastructure on the environment.

However, in other infrastructure areas, there is a lot more to be done

Nevertheless, there remain major significant challenges across sectors, particularly to reduce emissions. Key areas where infrastructure needs to improve performance:

- emissions from electricity and heat are still too high, as the electricity sector will need to reduce emissions to near zero by 2035, and little progress has been made so far on heat decarbonisation, although the technologies to do so already exist

- emissions from transport have not been declining, despite improvements in engine efficiency, and, although electric vehicle charge point numbers are increasing, the pace needs to pick up to enable a transition to electric vehicles in the 2020s and 2030s

- asset maintenance issues undermine performance in some sectors, including ageing and leaky water pipes and potholes in local roads

- more than five million properties are currently at risk of flooding in England, including more than three million at risk of surface water flooding

- serious pollution incidents from water and sewerage have plateaued at an unacceptably high level and 32 per cent of water bodies in England do not have good ecological status due to continuous discharges from sewage, and seven per cent due to stormwater overflows

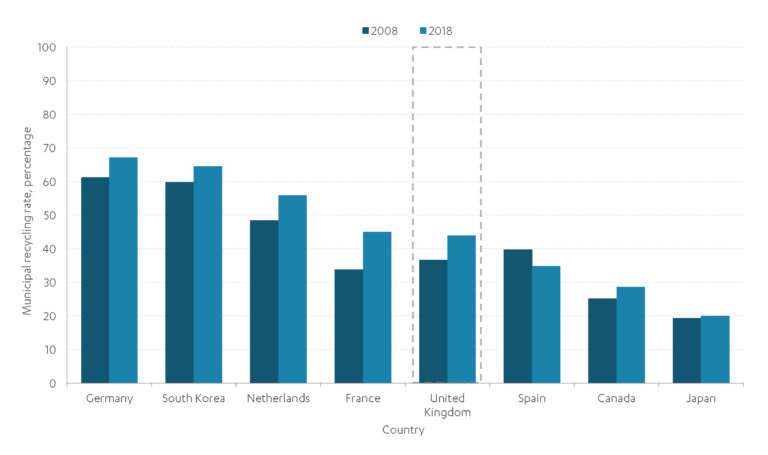

- recycling rates have plateaued and emissions from waste have begun to rise again, while the total waste generated in England is also increasing

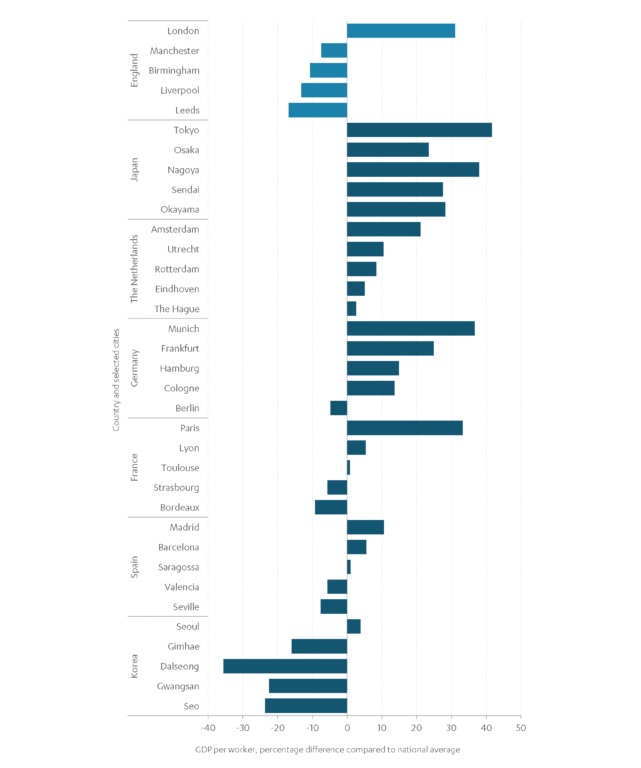

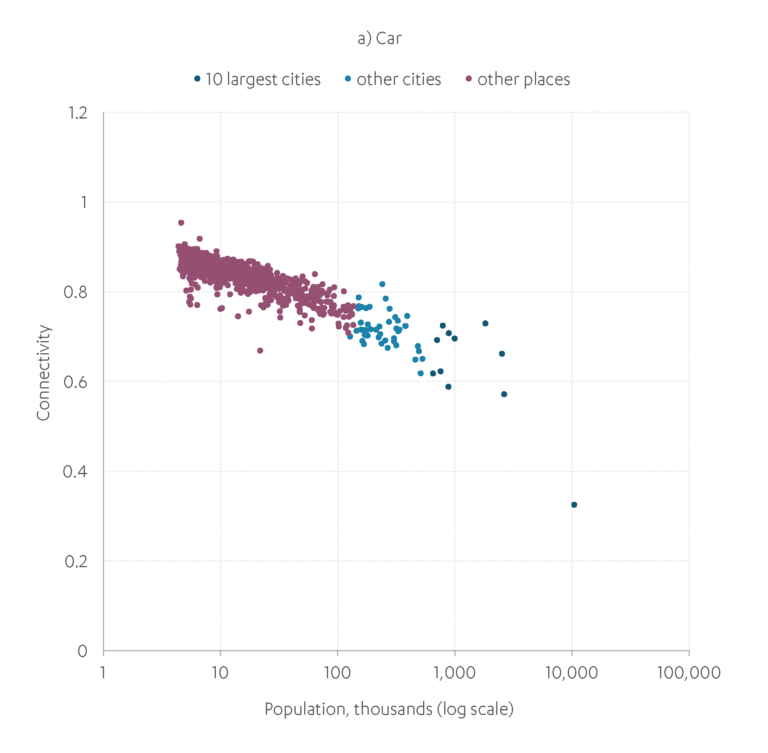

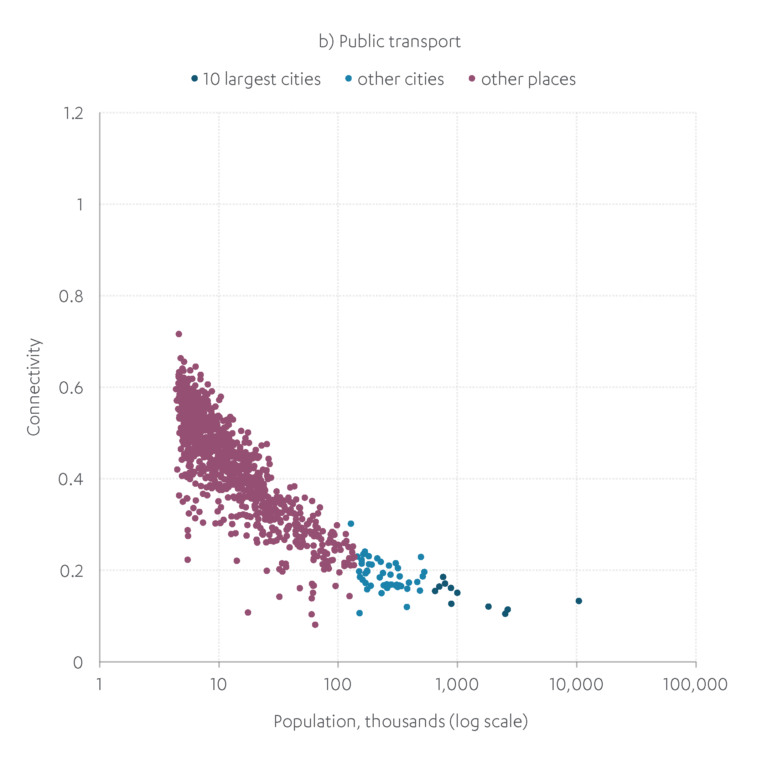

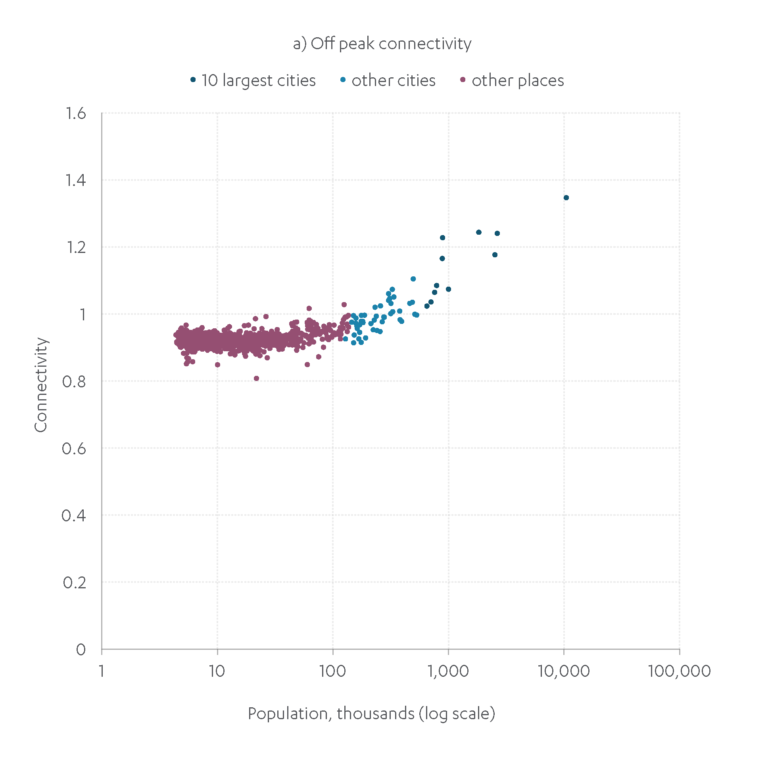

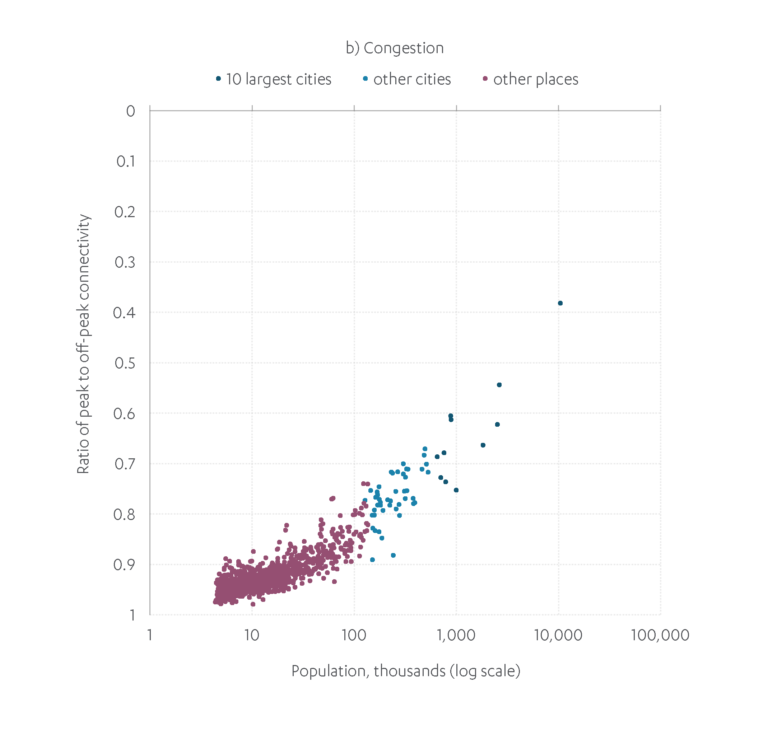

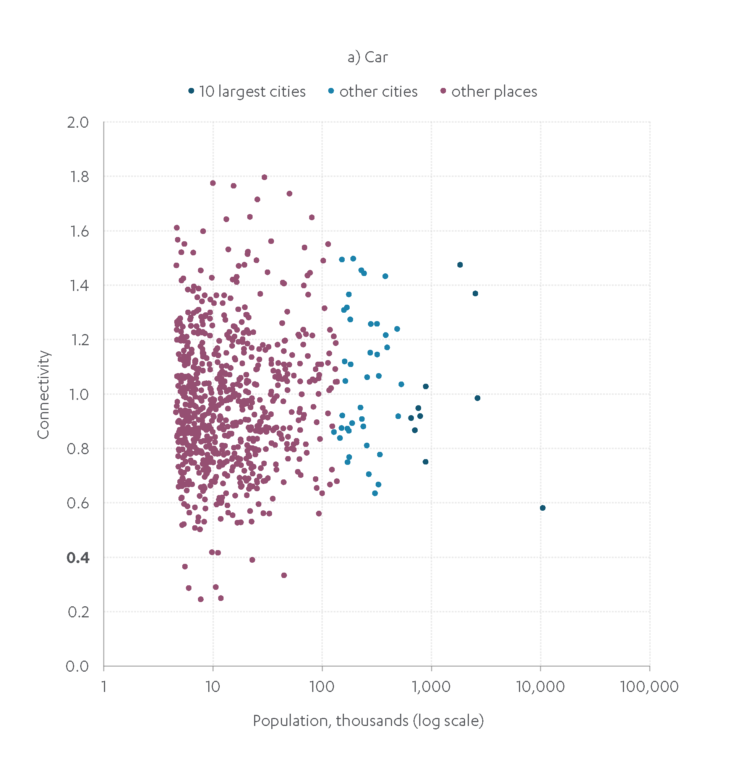

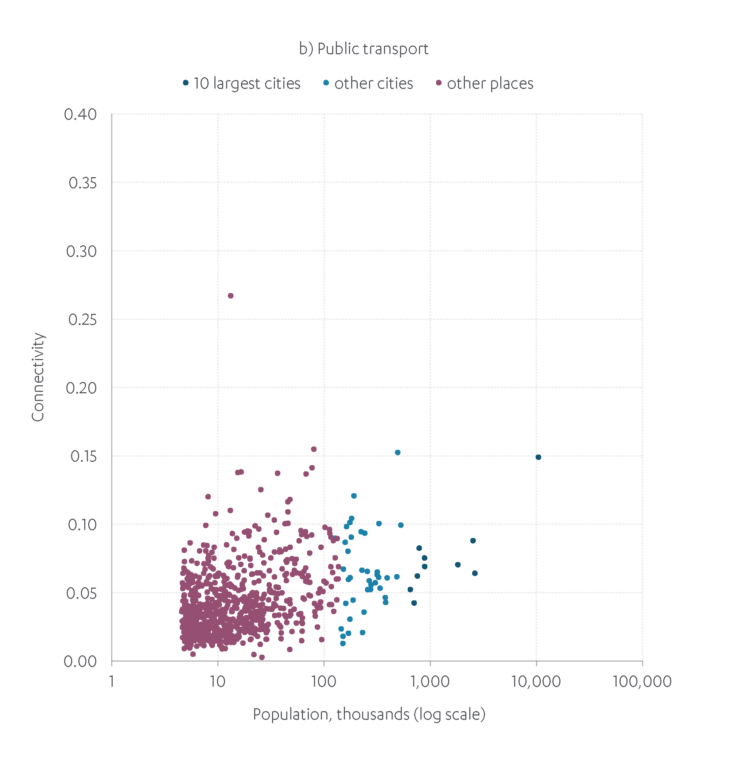

- urban transport connectivity is poor in many places, and the largest urban areas tend to have the worst connectivity, as congestion slows down journeys

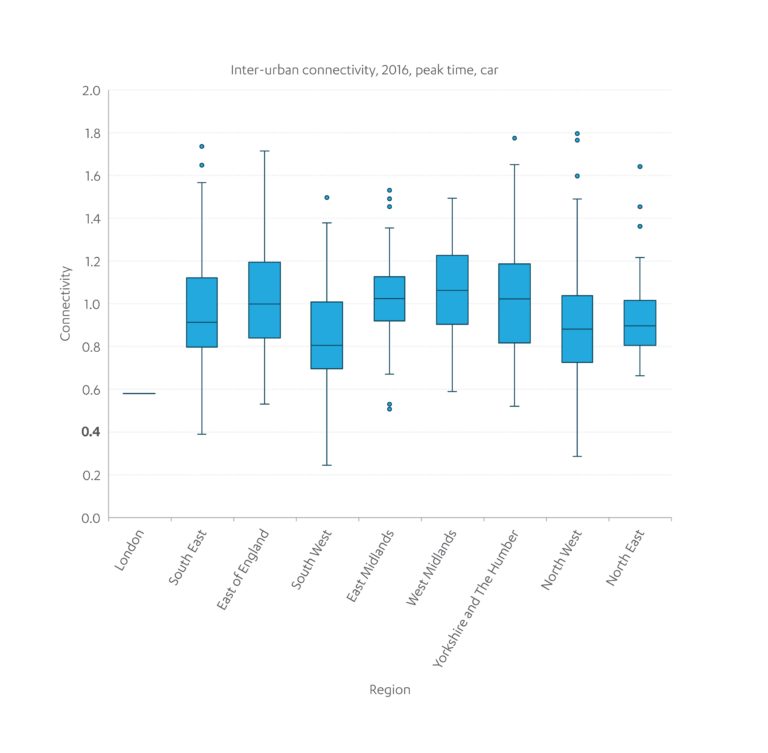

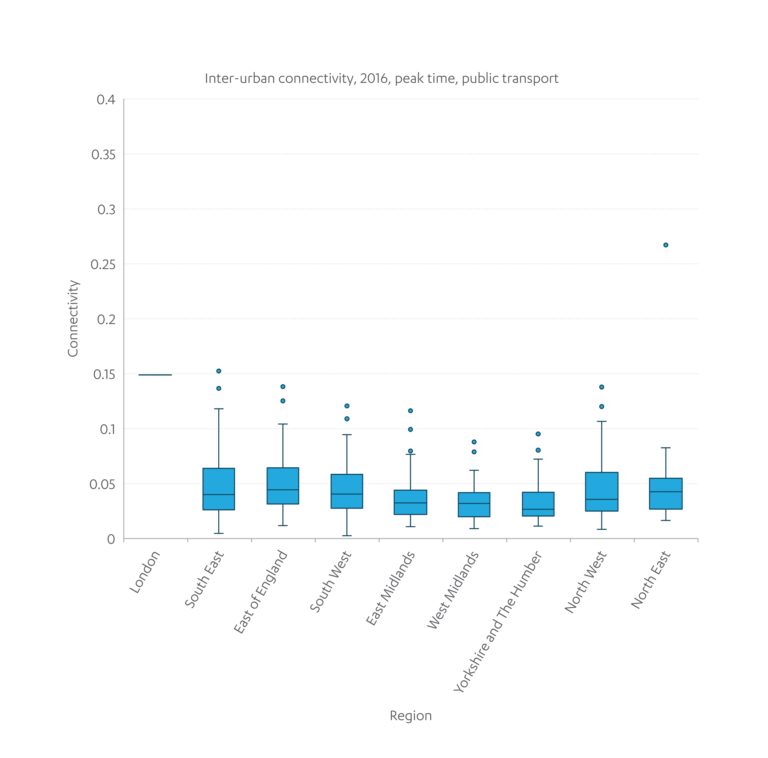

- there are wide variations in interurban connectivity between similar places, but with no clear regional patterns or trends.

Progress is already being made in some of these areas, including reducing emissions from electricity, enabling the transition to electric vehicles, and reducing the risks of flooding. However, there is still further to go. More detail on the performance of each sector is set out in annexes A-F.

The overall cost to households of infrastructure services has remained relatively stable over the last 10 years. At the same time, there have been significant increases in investment in many areas. Average energy bills rose from the mid-2000s until the mid-2010s and then gradually declined.

However, gas prices have risen significantly in recent months, pushing up the price of both gas and electricity, as gas remains a significant input into electricity generation. Domestic consumers have been shielded from some of this volatility due to the regulated cap on energy prices introduced from 2017. But prices have risen and are expected to rise further. Businesses have also been affected, especially those that are energy intensive. This inevitably creates serious problems for some households and firms.

Current high prices appear to be mostly due to temporary factors, including the effects of the Covid-19 pandemic. Prices may fall again, but volatility in prices is inherent in a system dependent on fossil fuels. As set out below, this price volatility reinforces the strategic need to transition to a low carbon energy system as soon as practicable.

Infrastructure also faces new challenges

As well as improving current performance, infrastructure must be prepared for future challenges, including from a changing climate, and behaviour change following the Covid-19 pandemic. And it should also take the opportunities offered by new digital technologies.

Infrastructure sectors are beginning to tackle the challenge of reaching net zero, reducing the impact of infrastructure on the climate. But the climate will also have impacts on infrastructure. Sectors must prepare for the risks of a changing climate, including increased incidence of flooding and drought.

And alongside climate change, there is another environmental crisis that must be addressed. Global assessments show that nature is declining at rates unprecedented in human history, with accelerating rates of species extinction and severe disruption to ecosystem services. Infrastructure contributes to this decline but can also help prevent it.

Finally, the Covid-19 pandemic may lead to long term changes in where people live and work. This, in turn, could lead to new patterns of infrastructure demand, especially in the transport sector, where there may be a change in the established levels of demand for different modes. Car use has already returned to levels seen before the Covid-19 pandemic, but in the longer term the way people use roads and public transport could be very different.

Key challenges for the second Assessment

Bold action and stable plans will be needed to address the existing issues and prepare for the coming challenges. The Commission has identified the key areas that it will develop recommendations on in the second Assessment. The Commission has focussed on those that have a good fit with the Commission’s remit, are strategically important, and are an issue where the Commission can add value, considering the current policy landscape and the Commission’s existing work. The key challenges are set out thematically below, and in Chapters 1-3.

Figure 0.2: Key challenges for the second assessment

Digital technologies present opportunities for all sectors

Higher quality digital infrastructure will present opportunities across the economy, including the opportunity to make improvements in all other infrastructure sectors. The adoption of digital technologies has the potential to cut costs, enhance service quality, improve resilience, and enable better demand management, across a range of infrastructure services. Sensors can be deployed across infrastructure assets to monitor their condition, allowing for more timely and efficient maintenance interventions. Real time data on road use could facilitate better traffic management and alleviate congestion. However, the adoption of digital technologies in infrastructure is patchy.

Challenge 1: The digital transformation of infrastructure – the Commission will consider how the digital transformation of infrastructure could deliver higher quality, lower cost, infrastructure services.

Reaching net zero

To meet its legally binding climate targets, the UK must reduce its overall greenhouse gas emissions by 78 per cent compared to 1990 levels by 2035, and to net zero by 2050. In October 2021 the government published its Net Zero Strategy setting out how it will deliver against its commitment to reach net zero emissions by 2050.

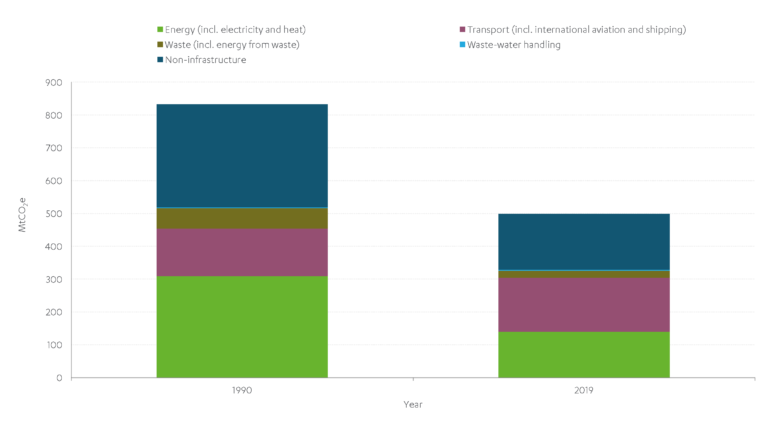

Economic infrastructure sectors generate a major part of the UK’s current emissions – in 2019, direct emissions from the energy, transport, waste, and wastewater sectors accounted for over 66 per cent of all UK greenhouse gas emissions. Reducing emissions is important to the public: the Commission’s social research, carried out in June 2021, found that people cited fighting climate change by reducing greenhouse gases as the top priority for the UK’s infrastructure in 30 years’ time.

Figure 0.3: Energy, transport and waste account for a large proportion of total UK emissions

Total UK greenhouse gas emissions, split by infrastructure sector, 1990 and 2019

Source: Department for Business, Energy & Industrial Strategy (2020), Final Greenhouse Gas Emissions National Statistics 2019

Reaching net zero will require high levels of investment, both to decarbonise existing infrastructure networks, and to build new ones, for example for carbon capture and storage, and hydrogen. This investment will ultimately need to be funded by either consumers (via bills) or taxpayers. The Commission will consider funding challenges in the second Assessment, including the overall affordability of required investment, the distribution of costs and savings across groups in society, and who should pay.

Decarbonising electricity generation

Electricity has made significant progress towards net zero, decarbonising faster than any other sector. In 2019, total emissions from electricity were around 60 MtCO2e, a reduction of 74 per cent since 1990. But the electricity system must now move away from fossil fuels – government has committed to electricity generation reaching nearly zero emissions by 2035 subject to being able to maintain security of supply. Over the same time, the electricity system will need to adapt to deliver on major increases in demand as other sectors decarbonise.

A net zero electricity system must also be secure and low cost. As the current energy price shock has shown, the volatility inherent in gas and oil prices – as internationally traded commodities – can have serious impacts on households and businesses. A low carbon electricity system, based more on long-lasting capital assets like wind farms and nuclear power plants, should reduce exposure to this kind of shock.

Challenge 2: Decarbonising electricity generation – the Commission will consider how a decarbonised, secure and flexible electricity system can be achieved by 2035 at low cost.

Decarbonising heat and improving energy efficiency

Decarbonising heat is complex, and progress has been slow. Total emissions from buildings in 2019 were around 90 MtCO2e, only a 17 per cent fall on 1990 levels. Most of these emissions arise from burning fossil fuels for heating. Providing zero carbon heat will likely require transitioning to a mix of electric heating and heat from hydrogen, alongside improving the energy efficiency of buildings with insulation to reduce the demand for energy for heat. The heat transition has so far proved difficult to implement, as it directly affects individuals and causes significant disruption in homes, buildings and at street level.

The government has recently published its strategy for decarbonising heat, via a gradual transition. It contains new funding commitments to support installation of low carbon heating systems in homes, with the goal that no new gas boilers will be sold by 2035. However, there are still major questions to be answered, including what level of insulation will be needed to efficiently operate heat pumps, whether hydrogen for heating will be available as a source of heat for all homes, what this means for the continuing use of the gas network, and how to deliver these major changes in people’s homes.

Challenge 3: Heat transition and energy efficiency – the Commission will identify a viable pathway for heat decarbonisation and set out recommendations for policies and funding to deliver net zero heat to all homes and businesses.

New networks to decarbonise hard to abate sectors

As well as transforming the existing infrastructure for electricity and heat, the UK needs new infrastructure networks to decarbonise, including:

- hydrogen networks, to help decarbonise hard to electrify sectors, such as heavy industry, shipping, aviation, heavy goods vehicles, parts of the rail network and heat

- carbon capture and storage networks, which will be needed to decarbonise parts of industry, hydrogen production, electricity generation (from sources such as waste incineration or biomass), and to enable engineered greenhouse gas removals.

Challenge 4: Networks for hydrogen and carbon capture and storage – the Commission will assess the hydrogen and carbon capture and storage required across the economy, and the policy and funding frameworks needed to deliver it over the next 10-30 years.

Climate resilience and the environment

Economic infrastructure has generally proved resilient to shocks and stresses over recent years, although good asset management will be important in future. Climate change will increase a variety of risks that affect economic infrastructure in the coming decades, with floods and drought a key risk.

Alongside climate change, there is another environmental crisis. Global assessments show that nature is declining at rates unprecedented in human history, with accelerating rates of species extinction and severe disruption to ecosystem services. Infrastructure contributes to this decline in natural capital and biodiversity but can also help prevent it. The Commission supports an ‘environmental net gain approach’ for all infrastructure projects (which includes, but is wider than, biodiversity net gain), ensuring that developers leave the environment in a measurably better state than they found it.

There are challenges in some sectors that affect the government’s objectives from the 25 Year Environment Plan, including minimising waste, and ensuring clean air and clean and plentiful water. The challenges under ‘reaching net zero’ will help to address the clean air objective, while the Commission’s previous recommendations supported the objective on clean and plentiful water. However, the net zero target means that the Commission will need to revisit its work on waste in the second Assessment, including considering how to further increase recycling. The government has also committed to move to a more circular economy, which could have wider implications for the sector.

Resilience must be embedded in asset management approaches

Good asset management requires managing infrastructure assets so that they can deliver services in a cost effective and timely way. This will be crucial to maintain resilience and performance as existing pressures increase or new ones emerge. There is already concern about the condition of assets in some sectors – the UK is still reliant on infrastructure built during the nineteenth century, including roads, railways, tunnels, water pipes and sewers. Some older components can be at greater risk of failure as they were not constructed to be resilient to extreme weather. There is also a lack of data on asset condition, and in some cases, deterioration is not noticed until a failure occurs. Furthermore, decision making frameworks can undervalue maintenance and disincentivise good asset management.

Challenge 5: Asset management and resilience – the Commission will consider how asset management can support resilience, barriers to investment, and the use of data and technology to improve the way assets are maintained.

Surface water management is a key resilience challenge

Droughts and floods will be a key risk for infrastructure as the climate changes. Government and industry are making progress on drought resilience and coastal and river flooding, following the Commission’s recommendations in the first Assessment. However, surface water flooding, which the Commission has not yet considered in detail, presents a risk to more than 3 million properties.

Multiple organisations are currently responsible for assets that affect surface water flooding, including local authorities, drainage boards, highways authorities and water companies. Relatedly, reducing sewer overflows, and the pollution they cause, will be a key challenge for the water and wastewater sector in the future. The government is making improvements in this area, but the scale of the challenge may require a more fundamental review of current arrangements. In the second Assessment, the Commission will carry out a dedicated study, as requested by government, on effective approaches for managing surface water in England. This will consider issues of planning, funding and governance arrangements, as well as the role of data and nature based solutions.

Challenge 6: Surface water management – the Commission will consider actions to maximise short term opportunities and improve long term planning, funding and governance arrangements for surface water management, while protecting water from pollution from drainage.

The Commission will deliver this as a separate study and report to government by November 2022, in advance of its other recommendations.

The waste sector can support the move to a circular economy

Waste infrastructure helps to protect the environment by enabling the safe collection, processing and disposal of municipal and industrial waste, preventing harmful waste products from entering the natural environment. The government has framed its waste objectives as part of the move to a more circular economy – one where products and materials are kept in productive use for longer, and the environmental impacts from extracting raw materials are reduced. In the second Assessment, the Commission will consider additional changes needed in the waste sector to enable the move to a more circular economy and to reduce the environmental impacts of waste. This will include looking at ways to increase recycling rates for municipal and construction waste and deliver the infrastructure needed to achieve net zero. It will also look at waste processing capacity and interdependencies with other economic infrastructure sectors including energy and water, and construction waste.

Challenge 7: Waste and the circular economy – the Commission will examine the role of the waste sector in enabling the move towards a more circular economy.

Supporting levelling up

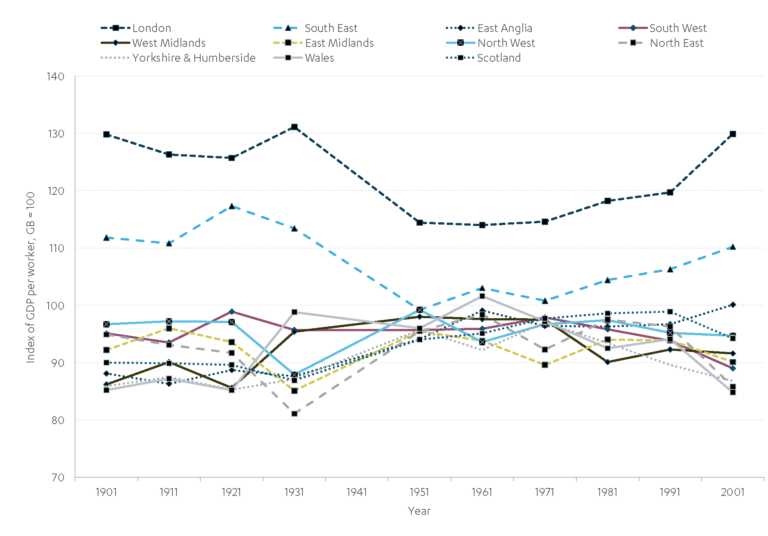

The government has set itself the ambition of ‘levelling up’ outcomes across the UK, reducing disparities between different towns, cities and regions. These variations are caused by multiple interacting factors. Addressing these disparities is hard. Infrastructure can help address them, but it cannot do so singlehandedly.

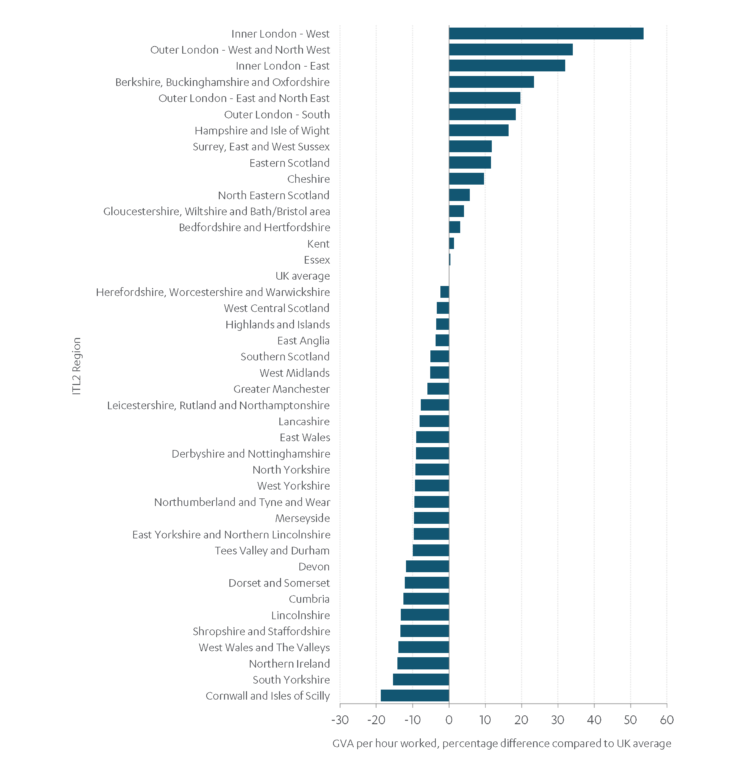

Productivity potential varies as different parts of the country play different roles in the economy, and different places have different economic densities – for example, it is not realistic to have the same productivity in rural Cumbria as in central Manchester. While no two places are exactly the same, the Commission will look at broadly comparable places to assess economic potential.

While most infrastructure sectors can have some impact on outcomes, improvements in the transport sector can improve quality of life and help address constraints to growth and, with the right conditions, contribute to economic transformation in particular places – for example, major rail stations and other nationally significant infrastructure projects can offer significant potential for urban regeneration, and these opportunities should be maximised.

The Commission has made recommendations in the past to support levelling up, covering:

- Devolved powers and funding for cities and towns to develop locally led infrastructure strategies: Infrastructure strategies need to be developed and determined locally, by people who understand the needs and strengths of the area.

- The need for infrastructure strategies to form part of wider economic strategies: While infrastructure can improve productivity and make places more liveable, it is not the whole solution – factors like skills and education also have an important role to play and therefore need to be aligned to infrastructure investment.

- The need for local capacity to deliver these strategies: Government should make expert support and advice available to help those local authorities where capacity is an obstacle to developing and delivering their infrastructure strategies.

In the second Assessment, the Commission will take account of where places are not achieving their economic potential to identify where interventions are likely to deliver significant benefits – for example identifying where growth could be unlocked by increasing capacity in congested city centres – and consider how these interventions can improve both productivity and quality of life in the places concerned.

In the energy sector, the Commission will consider opportunities for major investments in new low carbon infrastructure to support levelling up by boosting growth in lower productivity places – the development of offshore wind energy has already created new opportunities for coastal towns close to large wind farms, such as Grimsby. The Commission will also analyse how each of its recommendations reduce regional differences and support improvements in national productivity.

Improved connectivity and reduced congestion can boost urban productivity

Before the Covid-19 pandemic, many major cities suffered from congestion and poor public transport connectivity, preventing goods, services and people from travelling in an efficient and sustainable way. Overcrowded or slow transport networks limited the ability of businesses and workers to locate in dense city centres, which has been a major barrier to urban productivity and growth.

The Covid-19 pandemic may lead to new travel patterns, changing the established levels of demand for different modes. Car use has already returned to levels seen before the Covid-19 pandemic, but in the longer term the way people use roads and public transport could be very different. Urban transport strategies need to be robust to different future scenarios.

The busiest cities with the most growth potential may need very large scale transport capacity projects, or network extensions allowing people in nearby towns to work some days in a central location. Demand management policies such as congestion charging may also be needed to maximise the benefits of transport for agglomeration and productivity.

Challenge 8: Urban mobility and congestion – the Commission will examine how the development of at scale mass transit systems can support productivity in cities and city regions and consider the role of congestion charging and other demand management measures.

A multi-modal transport strategy can support regional growth

Investment in interurban road and rail can support regional growth. Transport connectivity varies significantly between places, but there is not an obvious north-south or rural-urban divide in performance. Furthermore, technological innovation, decarbonisation and behaviour change all mean that patterns of transport demand, and ways to meet that demand, may be very different in future. It is difficult to determine the optimal balance of investment between different places and modes. A multi modal transport strategy could help the country plan more effectively for sustainable growth, quality of life outcomes and the shift to net zero, optimising the use of different accessible modes.

Challenge 9: Interurban transport across modes – the Commission will consider relative priorities and long term investment needs, including the role of new technologies, as part of a strategic multimodal transport plan.

Next steps

The Commission welcomes views on the themes and challenges it has identified for the second Assessment. Interested parties are encouraged to respond to the Call for Evidence questions set out in this document. The Commission will also hold a programme of events during the call for evidence period and in the run up to the second Assessment, to explore policy questions in detail with regional and sectoral stakeholders.

The Commission will also research the views and preferences of the public to shape its recommendations. The Assessment will be supported by expert panels of industry specialists, academics and regulators who will assess and challenge the Commission’s emerging thinking, and by its Design Group and Young Professionals Panel.

The Commission will take a range of approaches to manage uncertainty, including that created by the Covid-19 pandemic, by making recommendations which balance the risks of major investment, making complementary recommendations, and planning for future decisions. The Commission will use a range of scenarios, to be published in spring 2022.

Cross-cutting analysis

The Commission will carry out cross-cutting analysis to inform the policy options and assess the impact of recommendations in the Assessment across six categories:

- bills impact: the second Assessment will show the total costs of recommendations that will be raised through bills, including assessing the impact of the Commission’s recommendations on household bills overall, in line with its economic remit

- public spending impact: the Commission will set out the impact of its recommendations on gross public investment in economic infrastructure, in line with its fiscal remit

- distributional impacts: assessing whether recommendations will have disproportionate impacts on specific groups of people

- climate change impact: assessing the impacts of economic infrastructure and the Commission’s recommendations on greenhouse gas emissions

- environmental impact: assessing how the economic infrastructure and the Commission’s recommendations affect the UK’s natural capital and biodiversity

- regional impacts: assessing whether recommendations will have disproportionate impacts on regions.

The Commission will look at the appropriate policy, regulatory and funding mechanisms to meet the infrastructure needs covered by the recommendations in the second Assessment and will consider the most effective decision-making models for infrastructure, balancing national and local needs and priorities. Recommendations will also be guided by the Commission’s design principles for national infrastructure: climate, people, places, and value.

Next Section: 1. Introduction

Ahead of the second National Infrastructure Assessment, the Baseline Report sets out an evaluation of the performance of the six infrastructure sectors in the Commission’s remit, identifies nine key infrastructure challenges for the second Assessment and asks Call for Evidence questions on these topics. The key challenges are grouped under three strategic themes: reaching net zero, climate resilience and the environment, and supporting levelling up.

1. Introduction

Ahead of the second National Infrastructure Assessment, the Baseline Report sets out an evaluation of the performance of the six infrastructure sectors in the Commission’s remit, identifies nine key infrastructure challenges for the second Assessment and asks Call for Evidence questions on these topics. The key challenges are grouped under three strategic themes: reaching net zero, climate resilience and the environment, and supporting levelling up.

Figure 1.1: Devolved administration responsibilities, by infrastructure sector

| Devolved administration responsiblity | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Sector | Northern Ireland | Scotland | Wales |

| Digital | Reserved | Reserved | Reserved |

| Energy | Devolved, except nuclear | Reserved, except energy efficiency | Reserved, except energy efficiency |

| Flood risk | Devolved | Devolved | Devolved |

| Transport | Devolved, except aviation and maritim | Largely devolved, except aviation and maritime | Road transport largely devolved, most rail, aviation and maritime reserved |

| Waste | Devolved | Devolved | Devolved |

| Water and wastewater | Devolved | Devolved | Devolved |

The first Assessment was published in July 2018.1 Since then, it has shaped infrastructure policy across the UK. The government’s National Infrastructure Strategy, a formal response to the Assessment, aligned closely with the Commission’s recommendations.2

The Baseline Report has three key functions:

- setting out an evaluation of the performance of the six economic infrastructure sectors

- identifying the nine key future infrastructure challenges for second Assessment, which will set out recommendations to address them

- inviting views on the set of challenges it has identified through call for evidence questions.

The Commission has identified the key challenges that it will consider in the second Assessment based on issues identified through the performance metrics, progress that is already being made, future trends and the public’s priorities as identified through social research. The Commission has also focussed on those that have a good fit with the Commission’s remit, are strategically important, and are an issue where the Commission can add value, considering the current policy landscape and the Commission’s existing work.

In October 2021, the Commission was given a new objective to support climate resilience and the transition to net zero carbon emissions by 2050. The Commission is confident that the key challenges identified are consistent with this new objective – the Commission has considered both climate resilience and net zero in its work to date,3 and both are strategic themes in this Baseline Report. Chapters 2-4 set out how each strategic theme aligns to all four of the Commission’s objectives.

Alongside a cross cutting digital challenge (see section 1.4), a further eight challenges have been identified, which are grouped under three strategic themes:

- reaching net zero

- climate resilience and the environment

- supporting levelling up.

The key challenges the Commission has identified are set out in figure 1.2.

Figure 1.2: Key challenges for the second assessment

The Commission will publish the second Assessment in the second half of 2023. The Commission – and the Assessments – take a long term view, making recommendations over the next 10-30 years and encouraging long term, stable infrastructure policy. Many recommendations from the first Assessment – or from the Commission’s studies, see box 1.1 – are therefore still relevant. In addition, government has made progress in implementing many of the Commission’s existing recommendations, where they were endorsed, or its own approach where they were not. The Commission will continue to monitor delivery but will not generally revisit these issues.

However, in some areas – such as the government’s commitments on the environment and climate, the effects of the Covid-19 pandemic, or technologies that can support infrastructure – the context has changed since the first Assessment. Therefore, while the first Assessment made recommendations across all sectors, the second will focus on the remaining key challenges, areas where the Commission’s recommendations need to be updated, or where the Commission needs to address new issues.

Following the first Assessment, the Commission carried out a comprehensive engagement process with its staff and external stakeholders to gather feedback. The conclusions of this were published in a paper in March 2019.4 The Commission has taken this feedback into account in this document, and in the plans for the second Assessment.

Box 1.1 Commission studies since the first Assessment

Box 1.1: Commission studies since the first Assessment

Since the first Assessment, the Commission has published studies as requested by government on:

Freight: The Commission found that through the adoption of new technologies and the recognition of freight’s needs in the planning system, it is possible to decarbonise road and rail freight by 2050 and manage its contribution to congestion. The government welcomed the core themes of the Commission’s report and will develop these themes through the Freight Council and the Future of Freight strategic Plan.

Regulation: The Commission’s regulation study set out how regulators, industry and government must adapt to face the coming challenges of achieving net zero, ensuring resilience, and increasing digitalisation. The study looked at how to keep critical services affordable, ensure competition, and attract the right levels of investment and innovation. The government has responded to the Commission’s recommendations to improve regulation and will set out further details later this year.

Resilience: The Commission’s study examined how to improve the resilience of the UK’s water, digital, transport and energy infrastructure, including the key strategic changes required to meet forthcoming challenges while maintaining levels of service for users. Government has accepted the potential role for more and better resilience standards and stress testing, and will set out further details in the National Resilience Strategy.

Rail Needs Assessment for the Midlands and the North: To inform the government’s Integrated Rail Plan, the Commission developed a menu of options for a programme of rail investments in the Midlands and the North, using three different illustrative budget options. The Commission recommended an adaptive approach, beginning with a core set of programmes. [Integrated Rail Plan outcome].

Engineered greenhouse gas removals: The study set out that engineered greenhouse gas removals will become a major new infrastructure sector for the UK over the coming decades. It recommended that government ensure the first engineered removals plants are up and running no later than 2030, delivering 5-10 MtCO2e of removals per year. The government’s Net Zero Strategy has since set an ambition to deploy at least 5 MtCO2e of engineered greenhouse gas removals by 2030, rising to around 23 MtCO2e by 2035, and a plan to consult in 2022 on business models to incentivise investment.

Towns: This study focused on towns and suburban centres, considering the potential for both economic and quality of life benefits from infrastructure intervention in different types of towns. The Commission awaits government’s response.

1.2 Work informing the second Assessment

The Baseline Report forms part of a wide body of work to inform the second Assessment. The Commission has published a number of supplementary papers since the first Assessment, aside from its studies (see above) and annual monitoring reports, and more are planned in the run-up to the second Assessment.

The Commission’s interpretation of its objectives

The Commission is in the process of publishing discussion papers on its interpretation of its objectives, including two discussion papers published to date covering the first two objectives:

- Supporting sustainable economic growth across regions: Growth across regions sets out the relationship between economic infrastructure and local growth and identifies three pathways for infrastructure investment to help achieve economic outcomes in regional areas: addressing constraints to growth, contributing to transformation, and universal provision.5

- Improve competitiveness: Improving competitiveness identifies three ways in which infrastructure can contribute to competitiveness: improving access to markets, improving access to mobile labour and capital, supporting and being a source of globally significant clusters and assets.6

The Commission is planning to publish a discussion paper on its quality of life objective in spring 2022. It has also published a literature review on the impacts of infrastructure on quality of life, which sets out a rapid evidence assessment of the impact of each of the Commission’s six infrastructure sectors on quality of life.7 The Commission has recently been given a new objective to support climate resilience and the transition to net zero carbon emissions by 2050 and will consider in due course whether to publish a discussion paper on this objective.

Drivers of infrastructure supply and demand

Ahead of the first Assessment, the Commission published documents on drivers of infrastructure supply and demand.8 The theoretical relationships between each of these drivers and infrastructure supply and demand remain largely unchanged since the first documents were published, however there are some updates:

- Environment and climate change – Chapter 3 sets out the Commission’s up to date understanding of the impact of climate change on the infrastructure sectors, and the impact of sectors on the environment.

- Economy – The UK is still recovering from the historic shock caused by the Covid-19 pandemic. The Commission will consider the implications of this as more data emerges, based on forecasts from the Office for Budget Responsibility.

- Population and demography – An ageing population, and the impact of the UK’s exit from the EU mean that population projections have changed since the original paper was published. The Office for National Statistics is expected to publish updated projections in December 2021. The Commission will consider the impact of these once latest projections are available.

- Technological change – The original paper included a horizon scan of new technologies that could impact infrastructures supply and demand.9 The Commission will publish an update to this in spring 2022.

- Behaviour change – Since the first Assessment, the Commission has published a fifth paper on a driver of infrastructure supply and demand: Behaviour change and infrastructure beyond Covid-19.10 The Commission will continue to monitor the impacts of behaviour change as data emerges.

The Commission will publish updates to the drivers and publish the set of scenarios it will use to develop the second Assessment in spring 2022.

1.3 Assessment of the infrastructure sectors

Progress has been made in some areas since the first Assessment

The first Assessment was published in July 2018. Since then, it has shaped infrastructure policy across sectors. The government’s National Infrastructure Strategy,11 a formal response to the Assessment, aligned closely with the Commission’s recommendations, and there has been significant progress on many of the recommendations, including:

- access to gigabit capable broadband: the government has set out a clear vision to deliver gigabit capable broadband to at least 85 per cent of UK premises by 2025 – in late 2021 this was well underway, reaching over 50 per cent of premises12

- a shift to renewable electricity: there has been a shift towards a highly renewable electricity system, with almost 40 per cent of electricity generated by renewable sources in 201913

- electric vehicles: government has banned the sale of new petrol and diesel cars and vans in the UK from 2030,14 following the Commission’s recommendation that charging infrastructure should be delivered to enable this shift

- flooding: the government will invest £5.6 billion over the next six years to reduce the risk of flooding, following Commission recommendations15

- drought resilience: government and the water industry in England have taken on the Commission’s recommendations to increase water supply and reduce leakage16

- the UK Infrastructure Bank: the independent infrastructure financing institution the Commission recommended be established following the UK’s loss of access to the European Investment Bank was launched in June 202117

- design principles: the government endorsed the Commission’s design principles and recommendation for board level design champions on major infrastructure projects.18

Infrastructure has continued to perform well in some areas

The Commission’s performance assessment has identified several areas where infrastructure is performing well, including:

- access to mobile connectivity: 92 per cent of the UK landmass is covered by at least one mobile operator, with a funded plan to increase this to 95 per cent by 202619

- reliable energy supply: the energy sector delivers electricity and gas of reliable quality to consumers – loss of supply is rare, and interruptions to supply are reducing over time20

- access to clean water: the water sector delivers water of reliable quality to homes and businesses across England, with low numbers of service interruptions, and customers are generally satisfied with the water and wastewater services provided.21

Social research

In June 2021, the Commission carried out social research, with a range of respondents from across the UK, nationally representative by age, gender, region and ethnicity.

The research showed relatively high levels of confidence from respondents from across the UK that infrastructure will meet people’s needs over the next 30 years, with confidence increasing since the first Assessment. Only two sectors – flood resilience and waste – had lower than 70 per cent confidence, with the digital sector performing particularly strongly. This social research will shape the Commission’s approach to the second Assessment.

Figure 1.3: Public confidence in infrastructure has improved since the first Assessment

Percentage of respondents who were confident that the sector would meet their needs in the next 30 years, in 2021 vs in 2017 (ahead of the first Assessment)

Source: PwC (2021), NIA2 Social Research: Final report

The research also showed that the public increasingly believe that infrastructure should lead the fight against climate change and a plan for infrastructure should consider the impact of infrastructure on the environment.22

However, in other infrastructure areas, there is a lot more to be done

Nevertheless, there remain major significant challenges across sectors, particularly to reduce emissions. Key areas where infrastructure needs to improve performance:

- emissions from electricity and heat are still too high, as the electricity sector will need to reduce emissions to near zero by 2035,23 and little progress has been made so far on heat decarbonisation, although the technologies to do so already exist

- emissions from transport have not been declining, despite improvements in engine efficiency,24 and, although electric vehicle charge point numbers are increasing,25 the pace needs to pick up to enable a transition to electric vehicles in 2020s and 2030s26

- asset maintenance issues undermine performance in some sectors, including ageing and leaky water pipes and potholes in local roads27

- more than five million properties are currently at risk of flooding in England,28 including more than three million at risk of surface water flooding29

- serious pollution incidents from water and sewerage have plateaued at an unacceptably high level,30 and 32 per cent of water bodies in England do not have good ecological status due to continuous discharges from sewage, and seven per cent due to stormwater overflows31

- recycling rates have plateaued and emissions from waste have begun to rise again, while the total waste generated in England is also increasing32

- urban transport connectivity is poor in many places, and the largest urban areas tend to have the worst connectivity, as congestion slows down journeys33

- there are wide variations in interurban connectivity between similar places, but with no clear regional patterns or trends.34

Progress is already being made in some of these areas, including reducing emissions from electricity, enabling the transition to electric vehicles, and reducing the risks of flooding. However, there is still further to go. More detail on the performance of each sector is set out in annexes A-F.

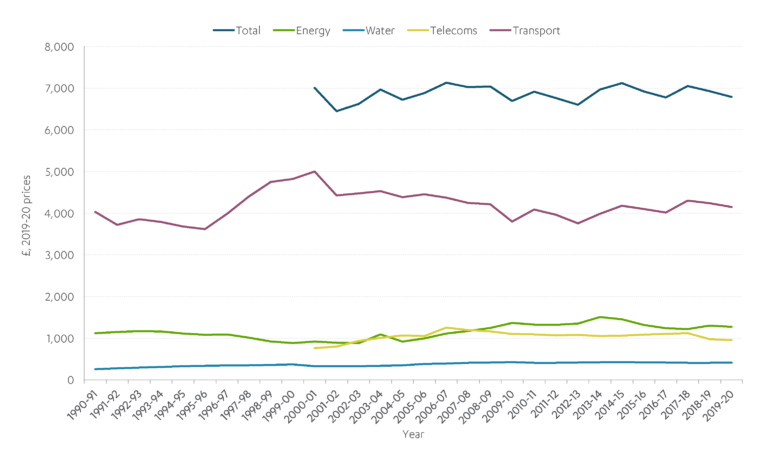

The overall cost to households of infrastructure services has remained relatively stable over the last 10 years.35 At the same time, there have been significant increases in investment in many areas. Average energy bills rose from the mid-2000s until the mid-2010s and then gradually declined.

However, gas prices have risen significantly in recent months, pushing up the price of both gas and electricity, as gas remains a significant input into electricity generation. Domestic consumers have been shielded from some of this volatility due to the regulated cap on energy prices introduced from 2017. But prices have risen and are expected to rise further. Businesses have also been affected, especially those that are energy intensive. This inevitably creates serious problems for some households and firms.

Current high prices appear to be mostly due to temporary factors, including the effects of the Covid-19 pandemic. Prices may fall again, but volatility in prices is inherent in a system dependent on fossil fuels. As set out below, this price volatility reinforces the strategic need to transition to a low carbon energy system as soon as practicable.

Figure 1.4: The overall cost to UK households of infrastructure services remains relatively stable despite increases in investment

Average annual household expenditure, £ (2019-20 prices, CPI deflated)

Source: DfT, ONS, Ofwat, Ofcom

Infrastructure also faces new challenges

As well as improving current performance, infrastructure must be prepared for future challenges, including from a changing climate, and behaviour change following the Covid-19 pandemic. And it should also take the opportunities offered by new digital technologies.

Infrastructure sectors are beginning to tackle the challenge of reaching net zero, reducing the impact of infrastructure on the climate. But the climate will also have impacts on infrastructure. Sectors must prepare for the risks of a changing climate, including increased incidence of flooding and drought.

And alongside climate change, there is another environmental crisis that must be addressed. Global assessments show that nature is declining at rates unprecedented in human history, with accelerating rates of species extinction and severe disruption to ecosystem services.36 Infrastructure contributes to this decline but can also help prevent it.

Finally, the Covid-19 pandemic may lead to long term changes in where people live and work. This, in turn, could lead to new patterns of infrastructure demand, especially in the transport sector, where there may be a change in the established levels of demand for different modes. Car use has already returned to levels seen before the pandemic, but in the longer term the way people use roads and public transport could be very different.37

Call for evidence questions

This document contains call for evidence questions on each of the nine challenges. These are mostly set out where the challenge is identified. However, there are several cross cutting call for evidence questions that are relevant across all nine challenges, set out below. A summary of call for evidence questions and information on how to respond is set out in chapter 5.

Question 1: Do the nine challenges identified by the Commission cover the most pressing issues that economic infrastructure will face over the next 30 years? If not, what other challenges should the Commission consider?

Question 2: What changes to funding policy help address the Commission’s nine challenges and what evidence is there to support this? Your response can cover any number of the Commission’s challenges.

Question 3: How can better design, in line with the Design Principles for National Infrastructure, help solve any of the Commission’s nine challenges for the next Assessment and what evidence is there to support this? Your response can cover any number of the Commission’s challenges.

Question 4: What interactions exist between addressing the Commission’s nine challenges for the next Assessment and the government’s target to halt biodiversity loss by 2030 and implement biodiversity net gain? Your response can cover any number of the Commission’s challenges.

Question 5: What are the main opportunities in terms of governance, policy, regulation and market mechanisms that may help solve any of the Commission’s nine challenges for the Next Assessment? What are the main barriers? Your response can cover any number of the Commission’s challenges.

1.4 Digital technologies present opportunities for all sectors

The Commission made recommendations on the availability and quality of digital infrastructure in the first Assessment, and the government is making good progress delivering on this, as set out above. The Commission will continue to monitor government progress in these areas through the Annual Monitoring Report but does not plan to undertake new work on network roll-out as part of the second Assessment. Instead, the Commission will turn its attention to how the widespread availability of fixed and mobile networks and services can be used in other infrastructure sectors to deliver better services at lower cost.

Higher quality digital infrastructure will present opportunities across the economy, including the opportunity to make improvements in all other infrastructure sectors. Adoption of digital technologies has the potential to cut costs, enhance service quality, improve resilience, and enable better demand management, across a range of infrastructure services. Sensors can be deployed across infrastructure assets to monitor their condition, allowing for more timely and efficient maintenance interventions. Real time data on road use could facilitate better traffic management and alleviate congestion. However, the adoption of digital technologies across infrastructure sectors is patchy. The second Assessment will consider barriers that are preventing the adoption of new digital technologies in infrastructure, and what policy and regulatory interventions may be needed.

Challenge 1: The digital transformation of infrastructure – the Commission will consider how the digital transformation of infrastructure could deliver higher quality, lower cost, infrastructure services.

Question 6: In which of the Commission’s sectors (outside of digital) can digital services and technologies enabled by fixed and wireless communications networks deliver the biggest benefits and how much would this cost?

Question 7: What barriers exist that are preventing the widescale adoption and application of new digital services and technologies to deliver better infrastructure services? And how might they be addressed? Your response can cover any number of the Commission’s sectors outside digital (energy, water, flood resilience, waste, transport).

Next Section: 2. Reaching net zero

The effects of climate change, which are already evident in the UK and worldwide, can only be mitigated by cutting greenhouse gas emissions, fast. In 2019, two thirds of all UK greenhouse gas emissions arose from transport, energy, waste and wastewater infrastructure. While progress has been made in these sectors, they all need to decarbonise further. And the move to net zero will also require new infrastructure networks for hydrogen and carbon capture and storage.

2. Reaching net zero

The effects of climate change, which are already evident in the UK and worldwide, can only be mitigated by cutting greenhouse gas emissions, fast. In 2019, two thirds of all UK greenhouse gas emissions arose from transport, energy, waste and wastewater infrastructure. While progress has been made in these sectors, they all need to decarbonise further. And the move to net zero will also require new infrastructure networks for hydrogen and carbon capture and storage.

In the second Assessment, the Commission will focus on the following key challenges:

- decarbonising electricity generation by 2035

- the heat transition and energy efficiency

- new networks for hydrogen and carbon capture and storage.

While the decarbonisation of surface transport is discussed in this chapter, transport will be covered as part of the challenges outlined in chapter 4. Similarly, waste will be considered in the circular economy challenge set out in Chapter 3. The water, floods and digital sectors have much lower emissions and so will not be considered as priority challenges for decarbonisation in the second Assessment, although the Commission will assess the emissions impact of all the recommendations it makes.

2.1 Infrastructure and net zero

In 2019, UK greenhouse gas emissions stood at around 500 MtCO2e, a reduction of 40 per cent since 1990.38 The UK has legally binding targets to reduce greenhouse gas emissions by 78 per cent by 2035 relative to 1990 levels,39 and to net zero by 2050.40 In October 2021, the government published its Net Zero Strategy – a summary of the actions it is taking, and plans to take, to deliver against its commitment to reach net zero emissions by 2050.41

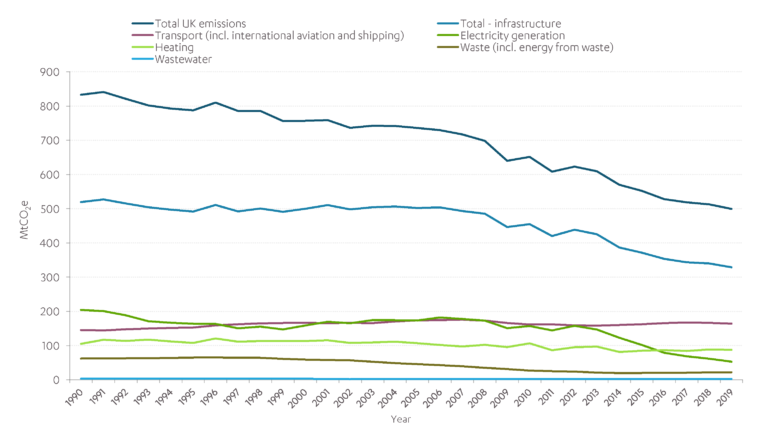

Reductions in emissions have so far been concentrated largely in the electricity sector, with only limited progress in most other infrastructure sectors (figure 2.1).

Figure 2.1: Total UK emissions have reduced since 1990, especially in electricity generation

Annual greenhouse gas emissions by infrastructure sector, 1990 to 2019

Source: Commission calculations using Department for Business, Energy & Industrial Strategy (2021), Final UK greenhouse gas emissions national statistics: 1990 to 2019

In 2019, two thirds of all UK greenhouse gas emissions arose from transport, energy, waste and wastewater infrastructure:

- transport (including surface transport, aviation and shipping) emitted around 165 MtCO2e (33 per cent of all UK emissions)

- electricity generation emitted around 50 MtCO2e (11 per cent)

- heat for residential, public sector, and commercial buildings emitted around 90 MtCO2e (17 per cent)

- waste emitted just over 20 MtCO2e (4 per cent)42

- wastewater emitted around 3 MtCO2e (less than 1 per cent).

In the transport sector, the route to net zero is clear for cars and vans, but more complicated for HGVs, rail, planes and ships. And while cars and vans can be decarbonised by the switch to electric vehicles, this needs to accelerate to meet the sixth Carbon Budget target – government must ensure public charge points are available to encourage take up.

In the energy sector, there is a clear route to decarbonise the electricity system. But it needs to happen fast – the electricity system must be near zero emissions by 2035. In heat, the challenge is different – the technologies to decarbonise heat exist, but how to deliver the necessary changes in homes and businesses is not clear.

To decarbonise the waste sector, emissions from landfill must be reduced. More detail on how the Commission will consider the waste sector in the second Assessment is set out in chapter 3. The Commission will also look at the emissions from energy from waste plants as part of the wider electricity system.

The Commission is not planning to consider process emissions from wastewater treatment as a priority in the second Assessment, as these represent a very small proportion of overall emissions.

The Commission’s other infrastructure sectors – the water, flood resilience and digital sectors – do not directly emit greenhouse gases in the way that power stations or cars do. Their reliance on energy and transport infrastructure does indirectly raise emissions, but, as those sectors decarbonise, the emissions from the water, flood resilience and digital sectors will also fall. The water, flood resilience and digital sectors are therefore not considered in this chapter.

The move to net zero will also require new infrastructure networks, including for hydrogen and carbon capture and storage. Government has set out strategies for both, however, there are still many questions to be resolved. It still needs to be determined how quickly these networks can be delivered, at what scale, and how plans can be coordinated.

Achieving net zero – a 100 per cent reduction in net (rather than gross) greenhouse gas emissions from 1990 levels – means that some sectors are still expected to emit a small amount of greenhouse gases in 2050. These will have to be offset by greenhouse gas removals, which the Commission considered in its 2021 report Engineered greenhouse gas removals.43

All infrastructure sectors have emissions ‘embedded’ in their construction process, and in their use of materials. Hydrogen and carbon capture and storage are two of the solutions to decarbonising the production of construction materials. The infrastructure needed to allow for this will be considered by the Commission.

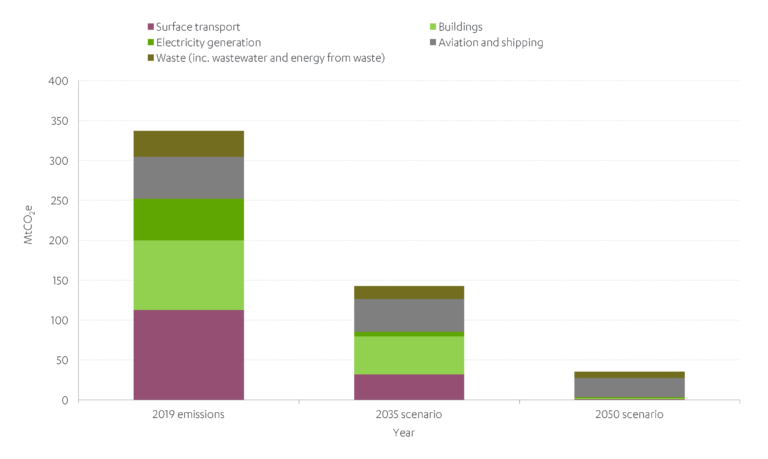

All infrastructure sectors need to decarbonise further, fast, to meet the government’s emissions targets for 2035 and 2050. While the legally binding net zero and sixth Carbon Budget targets only refer to total UK emissions across all sectors, the government has set out illustrative sectoral ranges for emissions reductions in its Net Zero Strategy.44 These ranges are similar to the illustrative roadmaps produced by the Climate Change Committee to meet both the sixth Carbon Budget and net zero target. The Commission uses these illustrative roadmaps as guidance for the expected decarbonisation path in its infrastructure sectors. The Climate Change Committee’s ‘balanced pathway’ scenario for each sector is shown in figure 2.2.

Many areas of economic infrastructure are devolved, see chapter 1. The Commission’s role is to advise the UK Government. This chapter therefore focusses on UK Government climate targets and areas of competence.

Figure 2.2: Some economic infrastructure sectors must decarbonise faster than others

Emissions reduction roadmaps for economic infrastructure in the Climate Change Committee’s ‘balanced pathway’ scenario

Source: Climate Change Committee (2020), Sixth Carbon Budget – Dataset. Note, allocation of emissions to sectors varies from the figures presented elsewhere in this report.

Box 2.1: Reaching net zero is a key theme for the Commission

Reaching net zero supports all four of the Commission’s objectives:

- Support sustainable economic growth across all regions of the UK: Reducing greenhouse gas emissions is vital for economic growth. The scale of the productivity impacts of heatwaves and other extreme weather is likely to be in the order of billions of pounds per year.45 The benefits from mitigating climate change will be felt across all regions. There are likely to be some economic benefits in areas where new low carbon industries are located, through jobs created in the construction and operation of these industries and through associated services. However, the transition away from oil and gas may have the opposite effect in places where these industries are centred.

- Improve competitiveness: Many of the UK’s existing competitive advantages are in high carbon industries. Net zero means that some of these industries face uncertain futures. But the UK can and should transfer its advantages – which lie across a broad range of professional, financial, and engineering and design services – to emerging low carbon industries, such as carbon capture and storage and electric vehicle technology.46 Getting ahead of this challenge now will maximise the UK’s future competitiveness as the global economy shifts towards net zero.

- Improve quality of life: Reducing greenhouse gas emissions is expected to help mitigate the impacts of climate change, which have significant impacts on quality of life in the UK and globally.47 The largest impacts are likely to be on health and availability (and therefore affordability) of food. It will also impact on quality of life through affecting infrastructure and access to infrastructure services, for example from flooding or overheated train tracks.48

- Support climate resilience and the transition to net zero carbon emissions by 2050: Reaching emissions targets in economic infrastructure will reduce emissions not only in those sectors, but also in the sectors that depend on them. Reducing greenhouse gas emissions will also help mitigate climate change, supporting climate resilience.

The Commission’s social research found that people increasingly rank reducing emissions as a priority for infrastructure. Respondents cited fighting climate change by reducing greenhouse gases as the top priority for the UK’s infrastructure in 30 years’ time.49

2.2 Transport

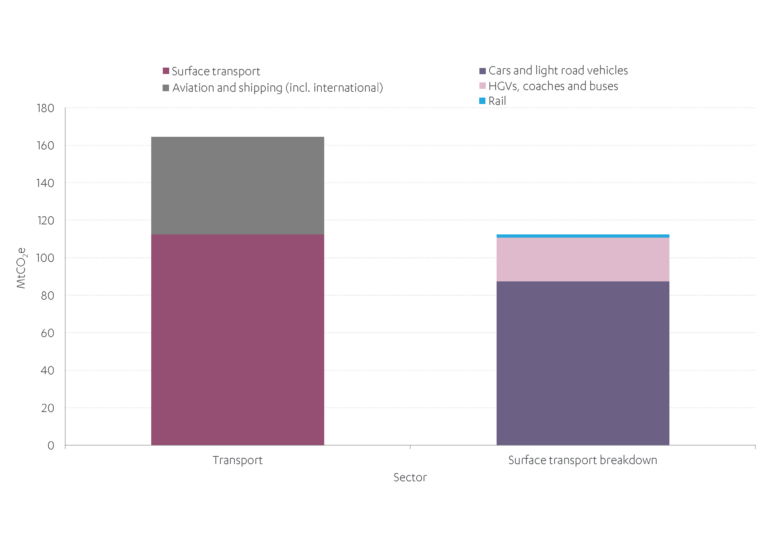

In 2019, greenhouse gas emissions from the transport sector stood at around 165 MtCO2e, or 33 per cent of total UK emissions that year. Emissions from transport broadly fall into two categories:

- surface transport, which emitted around 115 MtCO2e in 2019

- aviation and shipping, both domestic and international, which emitted around 50 MtCO2e in 2019.

Figure 2.3: Surface transport makes up two thirds of transport emissions

Annual greenhouse gas emissions by transport mode, 2019

Source: Commission calculations using Department for Business, Energy & Industrial Strategy (2021), Final UK greenhouse gas emissions national statistics: 1990 to 2019

Surface transport

In 2019, emissions from surface transport made up around two thirds of all transport emissions in the UK.50 These emissions have persisted at similar levels since 1990. Surface transport emissions arise from:

- cars, taxis, light vans, motorcycles, and mopeds, which produce just under 8o per cent of emissions from surface transport

- HGVs, buses and coaches, which emitted around 25 MtCO2e in 2019, around 20 per cent of surface transport emissions, with the majority coming from HGVs

- railways, which emitted less than 2 MtCO2e in 2019 – this is close to a 15 per cent reduction on 1990 emissions, despite a 115 per cent rise in passenger journeys.51

The Climate Change Committee’s balanced pathway scenario assumes emissions from surface transport will fall to 32 MtCO2e by 2035 and to 1 MtCO2e by 2050.52

Cars, taxis, light vans, motorcycles, and mopeds

The move to electric cars and vans will eliminate the majority of emissions from surface transport. In the first Assessment, the Commission recommended the roll out of charging infrastructure sufficient to enable 100 per cent electric new car and van sales by 2030.53 Government has since committed to ending the sale of new petrol and diesel cars and vans in the UK by 2030, and to working closely with Ofgem, and industry to ensure there is the charging infrastructure in place to support this.54

However, plans to deliver an electric vehicle charging network must accelerate if electric vehicle take up is to happen at the pace needed to meet the sixth Carbon Budget, which will require a significant shift to electric vehicles over the 2020s. Without available chargers, drivers will not have the confidence to make the switch. As of July 2021, there were around 24,300 public charging points.55 It is estimated that between 280,000 and 480,000 public charging points would be needed to support 100 per cent electric new car and van sales in 2030.56

In the National Infrastructure Strategy, government committed to publish an electric vehicle charging infrastructure strategy by November 2021.57 This is urgently required to help support the delivery of charging infrastructure that will encourage drivers to make the required switch to electric vehicles. It will also help both the market and local authorities plan the delivery of additional charging points. Ofgem has recently published its priorities for enabling the transition to electric vehicles, setting out plans to ensure that the networks are prepared for increased adoption, and that network connections are timely and cost effective. It also outlines how it will support off peak ‘smart charging’ using market incentives and support the sale of battery stored electricity back to the grid.58

HGVs, buses and coaches

Decarbonising heavy road vehicles presents a further challenge. The options being considered to decarbonise HGVs are hydrogen and electrification, either of which would require a change in existing fuelling infrastructure. The Commission has recommended that new diesel HGV sales should end by 2040.59 This year, the government committed to phase out the sale of new non zero emissions HGV’s by 2040.60 The government’s forthcoming ‘Future of Freight Plan’ must address the need for a comprehensive assessment of the infrastructure needed to enable freight HGV decarbonisation, including working with Ofgem and distribution network operators to plan any necessary infrastructure upgrades.

In its Transport Decarbonisation Plan, government committed to measures to boost zero emission bus fleets. Currently only two per cent of English buses are run on lower carbon fuel, such as electricity or hydrogen.61

Railways

In the rail industry, many of the intercity mainlines and almost all London commuter routes have already been electrified.62 Further electrification of the rail network will reduce emissions. The Commission has called for a rolling programme of electrification to be established but has noted that detailed work will be needed to establish which routes are the priority for early electrification.63 The Commission has also recommended that government publish a detailed strategy for achieving rail freight decarbonisation by 2050.64 The high costs associated with installing overhead line electrification pose a challenge for decarbonising all rail routes;65 for some, battery or hydrogen trains may offer an alternative means of decarbonising.66 Government has committed to encourage the development of battery and hydrogen trains in the Transport Decarbonisation Plan.

Chapter 4 sets out the Commission’s plans to look at improving urban and interurban transport. As the Commission develops transport recommendations for the second Assessment, it will ensure these recommendations are consistent with the government’s decarbonisation targets.

Aviation and shipping

In 2019, emissions from aviation and shipping stood at around 50 MtCO2e. Emissions from shipping have declined since 1990. But international aviation emissions were on a strong upwards trend prior to the Covid-19 pandemic, reaching close to 40 MtCO2e in 2019.

Figure 2.4: UK emissions from aviation and shipping in 2019

Source67

| Aviation | Shipping | |

|---|---|---|

| Domestic | 1 MtCO2e | 6 MtCO2e |

| International | 37 MtCO2e | 8 MtCO2e |